Cocktail Hour Under the Tree of Forgetfulness (15 page)

Read Cocktail Hour Under the Tree of Forgetfulness Online

Authors: Alexandra Fuller

ELEVEN DAYS AFTER OLIVIA DROWNED, the Rhodesian government distributed pamphlets in the Tribal Trust Lands with nine new instructions for black civilians:

1. Human curfew from last light to 12 o’clock daily.

2. Cattle, yoked oxen, goats and sheep curfew from last light to 12 o’clock daily.

3. No vehicles, including bicycles and buses to run either in the Tribal Trust Land or the African Purchase Land.

4. No person will either go on or near any high ground or they will be shot.

5. All dogs to be tied up 24 hours each day or they will be shot.

6. Cattle, sheep and goats, after 12 o’clock, are only to be herded by adults.

7. No juveniles (to the age of 16 years) will be allowed out of the kraal area at any time either day or night, or they will be shot.

8. No schools will be open.

9. All stores and grinding mills will be closed.

But far from containing the growing violence, the new controls only seemed to drive the war deeper underground and strangely further into each of us, as if it had become its own force, murderously separate from mankind, unfettered from its authors, wanton and escaping the conventions that humans have laid out for it in those chastened moments between conflicts.

Now when we drove through Zimunya, the place blew empty, as if ghosted. The minefields echoed with ever more explosions. And every morning, my mother rode her horse alone at the top of the farm, skirting the edge of the Himalayas, her gun carelessly slung across her back (instead of across her belly, the way she used to carry it), as if willing herself to be shot through the heart.

It no longer mattered whether Vanessa and I spoke in Received Pronunciation, or whether we spoke at all. The books Mum had read to us on her bed—hours of Rudyard Kipling, Ernest Thompson Seton, C. S. Lewis, Lewis Carroll, Laura Ingalls Wilder—were gone. In their place was silence. Now when the generator was kicked into life, my mother no longer played for us the vinyl recordings of Chopin nocturnes, Strauss waltzes or Brahms concertos, and meals were no longer interrupted by Mum’s toasting our uniqueness, “Here’s to us, there’re none like us!” Instead, there was the wireless, and the dread news—a civilian airliner shot down by guerilla forces in the southwest of the country, the survivors brutally massacred; an escalation of air raids by Rhodesian forces on guerilla training camps in Zambia and Mozambique; the slaying of foreign missionaries by God only knows whom (each side blamed the other).

AND THEN, on October 17, 1978, Umtali was mortared again in the middle of the night by guerilla forces coming into the country from Mozambique, an event that coincided confusingly with a vehement thunderstorm. At our boarding school we were awoken by our matrons trying to remain calm above the scream of bombs and the roll of thunder, “This is not a drill! This is not a drill!” We were hurried out of our beds and ushered down the fire escapes. Then we were pushed onto the floor in the front hall and mattresses were thrown on top of us with such hurried panic that our chins and elbows hit the cement. “Keep your heads down!” the matrons cried. “Silence! Quiet! Shut up!”

Miss Carr took roll call as if life depended on it and kids yelled their names back at her as if doing so might save them from being blown sky high. “Brown, Ann!” “Coetzee, Jane!” “Dean, Lynn!” “De Kock, Annette!” And there were kids crying for their mothers; people were praying out loud, shouting God’s name; and the matrons and teachers telling us to shut up and all the time the whining kaboom of another bomb and then more thunder. But above that overwhelming noise I could still hear the insistently loud voice of my sister from the other end of the makeshift bomb shelter, “Bobo! Bobo! Bobo!” and she didn’t let up until I shouted back, “Van, I’m here! It’s okay! I’m here, man!”

And then she went quiet under her crowded mattress and I went quiet under mine, but the bombs kept coming from the Mutarandanda Hills above Umtali. I imagined that this was how Vanessa and I would die, apt punishment for allowing Olivia to die first. And I suddenly understood that our aliveness and Olivia’s death was why my father had gone silent, and my mother had retreated so far from us that she seemed like a figure at the wrong end of a telescope, familiar but too distant to touch.

Then the attack stopped and against all natural laws we were still alive. The matrons came back through and lifted the mattresses off our heads. The boys doubled up in the junior boys’ dormitory and the girls were laid head to toe in the senior boys’ dormitory—layers of bodies. A few of us slept, but just before dawn we heard more artillery in the hills and we disentangled ourselves from one another, our legs unwrapping from legs, our intertwined fingers uncurling from fingers. “Take cover!” we yelled. We pushed one another and dove under our beds until Miss Carr came back through. “It’s okay. It’s okay. Those are

our

boys. They’re keeping you safe. Get back in your beds. It’s safe, those are

our

mortars.” Although from my perspective I suddenly knew two things with complete clarity: that regardless of who is firing them, all mortars sound the same; and that nothing would really ever be okay or safe again.

For the next two days the phone in the hostel rang off the hook, and one student after the other was summoned to the teachers’ smoke-filled office to speak to their parents. They returned smugly solemn and tear stained to report that their folks had been sleepless with worry about them. Mum and Dad never did telephone Vanessa and me to see if we were all right. So I thought perhaps they didn’t care, that they alone among Chancellor Junior School parents were not sleepless with worry about their children. But Vanessa said, “No, it’s not that. We’ve got to be okay on our own. You’ve got to be much braver than this, Bobo. They

expect

us to be brave now.”

A couple of weeks after the attack we went home for the weekend. Mum gave us both a T-shirt, and we understood it was a treat for not being wimpy (the way we were taken to the secondhand bookstore in Salisbury if we were brave at the dentist). The T-shirt showed a beer bottle in the shape of a grenade. Over it were the words COME TO UMTALI AND GET BOMBED!

“There,” Mum said. “That’s a joke; isn’t it funny? It’s a pun. Do you know what a pun is?” And then she looked at her hands and her eyes went very pale, “They asked us not to phone you. They said it would clog up the lines. They said we shouldn’t . . .” There was a pause. “You do know you must look after each other.” She gave us a shaky, uncertain smile. “You do know that, don’t you?”

Nicola Fuller and the End of Rhodesia

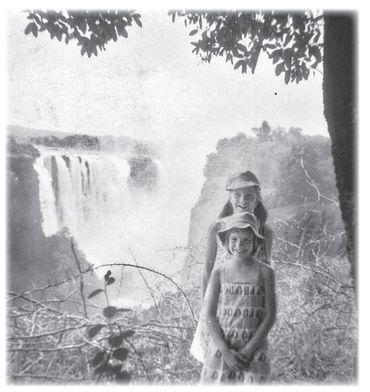

Bo and Van in front of Victoria Falls. Rhodesia, 1978.

M

y mother has no patience with questions that begin, “What if.” But I spend a great deal of my time circling that insensible eddy. What if we had been thinking straight? What if the setting of our lives had been more ordinary? What if we’d tempered passion with caution? “What-ifs are boring and pointless,” Mum says. Because however close to irreparably deep madness my mother had gone in her life, she does not now live in a ruined, regretful, Miss Havisham world and she doesn’t wish any of her life away, even the awful, painful, damaging parts. “What-ifs are the worst kind of postmortem,” she says. “And I hate postmortems. Much better to face the truth, pull up your socks and get on with whatever comes next.”

So the truth is this: it’s toward the end of the war (fin de everything) and our collective thinking has been so shaken up by the hallucinatory, seductive violence of it all that we can’t see our way even to a safer address somewhere else in Rhodesia, let alone out of the country. In any case, it doesn’t occur to us to leave. We see our lives as fraught and exciting, terrible and blessed, wild and ensnaring. We see our lives as Rhodesian, and it’s not easy to leave a life as arduously rich and difficult as all that.

In addition, leaving was treason talk, cowardly stuff. Mum makes a fist. “The Fullers aren’t wimps,” she says. “No, you don’t walk away from a country you

say

you love without a fight just because things get rough.” So the war escalated and escalated until very few families—rural, urban, black or white—were untouched by it and still we held on.

And then something happened that might have changed everything: my father’s father died. It took the English relatives a week before any of them thought to let Dad know. “The funeral is in two days,” Uncle Toe told Dad. “Sorry you won’t be able to make it.” My mother’s eyes go pale. “Well, we were only in Rhodesia,” she says. “It’s not as if we’d fallen off the face of the earth.” Within hours of receiving the telephone call, Dad got a cheap airplane ticket to England through Friends of Rhodesia, an organization that helped cash-strapped Rhodesians in emergencies. Then he found an Indian tailor in Umtali who agreed to put a suit together overnight. “Cash customer!” he announced. “I need a first-class suit for a third-class price.”

The next morning, Dad arrived in London. He changed into the new suit, hired a car and made it to the church two minutes before his father’s funeral was due to begin. “It was a showstopper,” Mum says. “Here was Tim back from Africa, sunburned and elegant.” As a former colony and now renegade country, Rhodesia made frequent and alarming headlines in the international press: RHODESIA—APARTHEID HEADS NORTH; RHODESIA FACES ITS FINAL HOUR; THE ARMAGEDDON IS ON. My father must have appeared to his relatives as someone suddenly showing up after being forever lost, dark continent vanished. “It couldn’t have shocked them more if Donald had sat up in his casket and ordered a pink gin for the road,” Mum says.

Dad took a place near a side door and looked at his fellow mourners. I picture them: Lady Fuller sitting stiffly silent in the front row, very elegant in her weeds (I knew so little of my grandfather’s second wife that I can think of her only as the name I have seen in lawyer’s letters, frozen in my imagination like a caricature from a Noel Coward play); Uncle Toe looking pale and serious in the pew behind her; in his wake a respectable showing of cousins, a few aunts, an uncle or two; then a row of solid navy types; and at the back my grandfather’s pig man.

After the vicar had made obligatory noises, everyone was asked to stand and sing “The Day Thou Gavest, Lord, Is Ended.” Then a toppish-brass navy officer took the pulpit and was eloquent on the subject of Captain Connell-Fuller’s career (skillfully steering his comments so that they sailed with considerable berth around the sore point of my grandfather’s never having achieved the much-desired rank of admiral, or even rear admiral). Then an elderly relative stood up and talked about Donald’s fondness for polo; the passion he’d developed in his retirement for raising pigs (the pig man gave an unhappy little wheeze); the time he blew up an oak tree at Douthwaite because it was getting in the way of his golf swing (general chortling). Then the congregation was asked to please stand again for a closing hymn, “Eternal Father, Strong to Save.”

After that, the old man’s coffin was carried out of the church, lowered into a hole in the ground and then as if the first clod of damp English earth on the wooden lid was a starting gun, the quarrel among his heirs began and didn’t let up for a generation and a half, by which time there was almost nothing left over which to fight. My mother closes her eyes and shakes her head, “There were, as you know, let us just say, some . . . problems with the will.” But Mum won’t elaborate. She flaps the air in front of her face, “Troubled water under the bridge and all that,” she says. “No point going on and on about it, is there?”

SO OUR FATE WAS one million per cent Rhodesian and even at this late date, we carried on fighting for Rhodesia as if it were the last place on earth, as if to lose it would be the same as losing ourselves. And life—the life that remained—went on in all its increasingly surreal impossibility. Vanessa and I continued to attend our segregated government school, where we prayed with renewed concentration and intensity at morning assembly for our fathers, our brothers, our boys, our men. Every six weeks Dad continued to disappear up in the Himalayas to fight guerilla forces, returning home exhausted, his right shoulder hunched like a broken wing from the perpetual weight of the FN rifle he carried. And Mum continued with farmwork: checking on the cattle by horseback in the morning; spending the afternoons in the tobacco fields; fretting over a pile of unpaid bills in the evenings.

She grew thin and sinewy, her feet calloused in the nailed strips of old tractor tires she now wore for sandals, her hands blistered and toughened. Whatever soft motherliness she had started out with—that smiling young woman in a gingham dress cradling a Shakespeare-saturated Vanessa on the lawn at Lavender’s Corner—was all but worn away. But then, one night in September 1979, Mum suddenly shoved herself back from the dining room table, a hand over her mouth, her eyes glassy with nausea. She glared at her plate, “Oh, the smell!” she said. Knowing the telltale signs, my father put down his knife and fork. “All right, Tub?”

Mum held up a finger, “I’ll be fine.”

She hurried from the room and Dad watched her retreating back. Then he pushed away his plate, lit a cigarette and put his head in his hands—the smoke curled up through his thinning hair. Outside, insects continued to pulse; Mum’s dairy cows screamed at a disturbance (a stray dog perhaps) and up in the hills there was a muffled explosion—something or someone on the cordon sanitaire detonating a mine. Whether she was ready for it or not, motherhood had imposed itself on Mum once again.

IT IS AN ANCIENT and misguided ruse, this introduction of a baby to trick the universe back into innocence, an effort to force the unraveling world to meet the comforting routine of a milk-scented nursery, a wish to have our sins washed clean by the blamelessness inherent in a newborn. But by late 1979, our country was beyond the reach of any child, however miraculous. The war had gone on so long and had become so desperate that it wasn’t a civil war anymore so much as it was a civilians’ war, a hand-to-hand, deeply personal conflict. The front line had spread from the borders to the urban areas to our doorsteps, and if we didn’t all have bloody hands, we were all related by blood to someone who did.

And now, awfully, the half-life of our violence had been extended indefinitely: the war had turned biological. Rhodesian Special Forces with the help of South African military had salted the water along the Mozambique border with cholera and warfarin; they had injected tins of food with thallium and dropped them into conflict zones; they had infused clothes with organophosphate and left them out for the guerilla fighters and for sympathizers of the guerilla cause. And they had planted anthrax in the villages; and more than ten thousand men, women and children living in the country’s Tribal Trust Lands were sickened with sometimes fatal necrotic boils, fevers, shock and respiratory failure in what would end up being the largest outbreak of anthrax among humans in recorded history.

All of this ongoing and deepening enmity, even as the leaders of the Rhodesian government and the leaders of the liberation forces were meeting at Lancaster House in London to discuss how to transition from rogue state to majority rule—from war to peace. Lord Carrington, British secretary of state for foreign and commonwealth affairs, opened the meeting tersely. “It is, I must say, a matter of great regret and disappointment to me and my colleagues that hostilities are continuing during this conference. . . .”

There had been peace talks before—held in the carriage of a train on the railway bridge across the Victoria Falls in 1975, for example—but the dialogue had always broken down. So it was something of a surprise—actually, to some it was an irredeemable blow—when on December 6, 1979, after three months of brittle negotiations, the Lancaster House Agreement was finally signed by all the relevant leaders. And just like that, it was settled. The war was over. Within a matter of weeks, the country would have a new name, Zimbabwe. And we would have a new prime minister, Robert Mugabe.

At school we were told that from now on, we were all equal. After morning announcements, we no longer sang “Onward Christian Soldiers” at assembly; now we sang “Precious Lord, Take My Hand,” which put our relationship to God in a whole new light, bordering on an erstwhile frowned-upon Public Display of Affection (until now, it would not have occurred to us to ask even our own parents to take our hands, let alone the Lord). And instead of praying for our boys, our brothers, our fathers, our men, we now prayed for peace, unity and forgiveness. Instead of mashed potatoes for lunch, we were now served sadza and we were encouraged to eat it the traditional way: rolled into balls in the palm of one hand and eaten with fingers. Our new black matron (much younger and more energetic than our old white one) told us that changing the words we used would be the beginning of changing our hearts. She told us that we should say

liberation fighters

instead of

terrs

; we should say

indigenous people

instead of

munts

; we should not call grown men “garden boys” or “boss boys”—we should call them “gardeners” or “headmen.”

“I SUPPOSE WE ALL SAW it coming,” Mum says, “but it was still a terrible shock to lose the war like that, lose the country, lose everything. One morning we woke up and it had all been decided and there was nothing left to fight for.” She leans back in her chair, her mouth folded at the edges as if the memory of this time exhausts her. “Everyone was going on and on about peace and reconciliation, but I knew it wasn’t going to work like that. No, I knew it wasn’t going to be simple and easy.”

Zimbabwean refugees who had spent the war in Mozambique came flooding back over the border and began squatting along the river at the top of Robandi, silting up the farm’s water supply and bringing tick disease into our cattle herds with their undipped livestock. “So we ended up with a whole new fight on our hands,” Mum says. “I wanted those squatters off our farm. They wouldn’t leave. We were harassed and exhausted; our nerves were in shreds.” Mum found herself unable to sleep, jumpy and tearful. “I suppose now we would say I had depression, but in those days we didn’t have a word for it.” (Actually, we did. Vanessa and I would have said Mum was having “a wobbly.”)

In light of this, Dad decided it would be best for everyone if we left Robandi, left the squatters, left the apricot-peach colored house and its constant reminders of everything we’d lost. He signed a year-long contract as section manager on Devuli Ranch, a vast, remote piece of nearly wild earth in the southeast of the country. His job was to round up the cattle that had gone feral over the seven-hundred-and-fifty-thousand-acre ranch during the course of the war. “A year away from it all,” Dad says. “Some real peace, a chance to breathe for a bit.”

Once a fortnight for the next year Dad packed a mosquito net, a sleeping bag, two bottles of brandy, a tin of coffee, some rice and a gun. Then he set up camp in the wild, unpeopled mopane woodlands far from any sign of civilization. At night he slept under a darkly innocent sky, a day’s full drive on rough bush tracks from the nearest human habitation. And I have no proof that day after day he walked six years of fighting out of his system, but it seems as likely an explanation as any for how he recovered most of the pieces of himself after that bush war.

To begin with, he brought Mum with him to camp. He set her up for the day on a camp chair in the shelter of a baobab tree with his best pair of binoculars and a new bird book. Then he went off to track and capture cattle. Once a week, he shot a young impala ram and hung it to cure in a wire safe so that there would always be fresh meat for her. He maintained a burning fire all night and he lit paraffin lamps around the camp so that she wouldn’t trip or stand on a snake if she needed to get up in the night.