Cocktail Hour Under the Tree of Forgetfulness (18 page)

Read Cocktail Hour Under the Tree of Forgetfulness Online

Authors: Alexandra Fuller

Mr. Zulu staked his claim on a small hill where he would be lord and master of all he surveyed and could see any unsuspecting, promising young woman coming from a mile off. Meanwhile, my mother made her way to a tree slightly tucked away at the sloping edge of Mr. Zulu’s hill. It was a tree of modest height, with a rounded spreading crown of leathery dark leaves and drooping branches. She thumped her walking stick on the ground under the tree. “Here,” she said. She stared up into the tree’s branches, “so full of birds,” and announced, “I want my house right here.”

Mr. Zulu came down from his hill and stood with my mother under the tree. He lit a cigarette and stared up at the tree’s canopy. Then he reached up and pulled at the leaves. “Do you know what this tree is?” he asked.

My mother frowned. “Maybe a false marula?” she tried.

Mr. Zulu shook his head, “No, Madam. This is the Tree of Forgetfulness. All the headmen here plant one of these trees in their village.” Mr. Zulu held his forearm steady as if to demonstrate the power of the tree. “You can plant it just like that, from one stick, and it is so strong it will become a tree. They say ancestors stay inside it. If there is some sickness or if you are troubled by spirits, then you sit under the Tree of Forget-fulness and your ancestors will assist you with whatever is wrong.” He nodded and took another drag of his cigarette. “It is true—all your troubles and arguments will be resolved.”

“Do you believe that?” Mum asked, but before Mr. Zulu could reply she waved her own question away. “I believe it’s true,” she said. “I believe it two million percent.”

Mum looked up into the branches of the tree again and she smiled. “Please bring me my camp chair, Mr. Zulu,” she said. “I think I will have my tea here today.” So Mr. Zulu went back to the truck to get Mum her chair. Dad, still weak from malaria, was lying under the tarpaulin watching the kettle boil over a mopane fire. “The madam has found the place for her house,” Mr. Zulu reported. Dad propped himself up on an elbow and squinted in the direction of the river. Backlit against the fierce afternoon sun, hands planted on her walking stick, was Mum—Nicola Fuller of Central Africa—mildly victorious under her Tree of Forgetfulness.

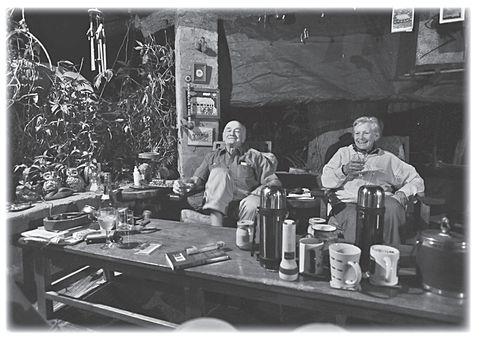

Nicola Fuller of Central Africa at Home

Mum and Dad, cocktail hour under the Tree of Forgetfulness. Zambia, 2010.

W

hen I step off the airplane and into the Immigration and Customs Hall at Lusaka International Airport, Mum and Dad are waiting to greet me. They are standing in front of everyone else, pinned right up against the glass. Dad is in a blue town shirt, a pair of baggy Bermuda shorts, a pipe in his mouth. Mum is tipsy with excitement, in a pinstripe shirt and khaki pedal pushers. As soon as she sees me, she starts jumping up and down, and flashing her V for Victoria sign as if I am the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic. “Whoo-hoo!” she hoots. “Whoo-hoo!”

But the closer I get to her, the less sure Mum is of what to do; she envelops me in a brief, uncomfortable embrace and tolerates a peck on the cheek. “Did they give you lots of yummy wine on the plane?” she asks. Dad—who has been looking mildly surprised since first glimpsing me (I have changed my hair color since the last time he saw me and while he can’t put his finger on the difference, he knows there is one)—pummels my shoulders affectionately and takes my suitcase. “Bloody hell, Bobo,” Dad says, and I know what he is about to say next—“How many pairs of shoes do you have in here?”—a persistent hangover from the time Mum took nothing but winklepickers and high-heel boots on their honeymoon to Tsavo National Park.

I am put in the bed of the pickup with an oil-bleeding generator, bags of fish food and my suitcase. “Are you sure you’ll be okay back there, Bobo?” Mum asks, although she knows it’s my preference.

“Fine,” I say.

“Yes, it’ll do her good after all that limousine treatment she’s been getting over there,” Dad says, patting the tailgate. He rolls down the window and pays the car guard. “Don’t spend it all on wine and women,” he advises, and then we’re off, whistling through the perfect Lusaka night—the city sweetly pungent with the smell of diesel engines, burning rubbish, greening drains—sparks from Dad’s pipe flying back around my shoulders and hair, for home.

AT THE TOP OF MY PARENTS’ garden at the fish and banana farm, there is a brick archway and wide brick steps leading past the Tree of Forgetfulness to an open-air kitchen where Big H spends her mornings preparing huge redolent stews of vegetables and cow bones for the dogs’ supper, and her afternoons frowning over the supper Mum is preparing for the rest of us. “Ever since Big H got television and started watching those cooking shows, she has started to look down her nose at my curries,” Mum says. Mum has always cooked whatever she can get her hands on: ropy chickens, mutton, crocodiles, frogs on the driveway—“They had deceptively promising thighs,” Mum says—and turned them into fragrantly wonderful meals. “Big H thinks you’re supposed to swear and sweat and have tantrums like Jamie Oliver,” Mum says. “Not my nice, calm wine-infused meals.”

On one side of the kitchen is the woodstove, its back to the garden; on the other, there is a small laboring fridge (in the heat it merely produces sweating butter or water-beaded bottles, nothing ever gets really cold). Behind Big H, on a shelf dedicated to their storage, are Mum’s nine orange Le Creuset pots. Their bottoms are permanently blackened with the drippings of the hundreds of curries and stews that have been cooked in them over the years.

To the right of the archway is a building containing my parents’ bedroom and Mum’s library with her collection of videos (musicals and operas mostly as well as British period dramas and a few nice, soothing murders); her books; and her art supplies. The top shelves are cluttered with carvings, ornaments and the brutalized bronze cast of Wellington (now missing both stirrups and reins, like a victim of a grueling Pony Club exercise).

To the left of the archway there is a two-roomed cottage comprising the guest bedroom and Dad’s office. It is a thatched, brick structure inclined to be porous to wildlife. I open the door and wait. Nothing launches itself at my ankles, so I make my way to the bed and sit down, feet drawn up onto the bed. Big H brings me a clean towel, then stands around surveying the place. “Frogs,” she observes at last, and leaves. As my eyes become accustomed to the gloom, I see what she means. The place is smothered in large, foam-nesting tree frogs, white as alabaster. They are hanging from the mosquito net, glued to the walls, attached to the door, hopping across the floor. Later, I find that if I drink half a box of South African wine and take a sleeping pill, a frog will become attached to my cheek while I sleep and will stay there unnoticed until morning. “How lucky for you,” Mum says. “You can write about that in one of your Awful Books.”

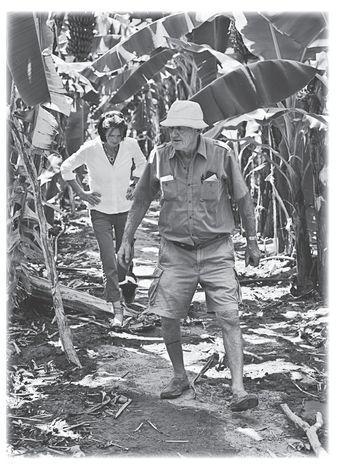

Bo barely keeping up with Dad on the farm. Zambia, 2010.

WORK ON THE FARM begins at dawn, while it is still cool, and I awake to find it well under way. There’s Mum marching up to her fish ponds with a walking stick and a collection of dogs in her wake. “Those kingfishers are very greedy and very naughty,” she says, waving her walking stick at a hovering shape over one of her ponds. There’s Dad striding down to inspect his bananas—“Thirty-four kgs for a first bunch!” he announces triumphantly. My parents’ farm is a miracle of productivity, order and routine—measuring, feeding, pruning, weeding, weighing, packing.

From the camp, Dad’s bananas appear as a green cathedral of leaves. In the early days of the farm, elephants would make their way onto the farm at night and raid the fruit, stripping leaves, crushing stems. “They make a terrific mess,” Mum says. Dad would wake up and hear them ripping through his plantation. “Talk about selective hearing,” Mum says. “He can’t hear a word I say, but let an elephant harm a hair on the head of one of his bananas and Dad bolts out of bed.” Dressed only in a Kenyan kakoi and his blue Bata slip-ons, he raced down to the field waving a torch, “Come on you buggers that’s enough of that. Off you go, go on!” Until eventually sleep deprivation forced Dad to put up an electric fence. “So that put an end to the elephants’ picnics,” Mum says.

Mum has taught herself everything she can about farm-raised tilapia—even flying with Chad Mbewe, her fish-section manager, to Malaysia for conferences on the latest techniques. “We both nearly died of cold in the icy air-conditioning,” Mum says. “You need a serious down jacket and a scarf. I came home with bronchitis.” In ten years, she has become the premier producer of fingerlings in the country, perhaps even the region. Her fish are famous for their quality, their ability to gain weight and their remarkably unstressed conditions. “Everyone has to be very calm and nicely turned out around Mum’s fish,” Dad warns. “You know what she’s like.” And it’s true; it’s not enough for Mum’s ponds to be efficient, they must also be pleasant for the fish

and

artistically pleasing, as if she is substituting her farmwork for something that in another time and place she might have painted (sheep and geese grazing mostly peacefully along the ponds’ edges; reeds picturesquely clumped at the corners; baobab trees, serene and ancient as a backdrop).

By midmorning, farmwork has been ongoing for five hours. Mum and Dad come in for breakfast, a meal consisting of pots and pots of tea, a slice of toast and a modest bowl of corn porridge. Then Dad puts his hat back on his head and Mum grabs her walking stick and her binoculars and out they go again. “Details, details, details,” Mum says. “The devil lives in the details.” But by early afternoon, the heat drives everyone indoors or toward shade and we retire to our frog-infested rooms for a siesta.

After our siesta and more tea, my parents are back out on the farm, Dad trailing a fragrant pulse of smoke from his pipe, Mum’s walking stick thumping the ground with every stride. The soil under the bananas is being sampled for effective microorganisms; the fingerlings in several of the ponds are being counted; the shepherds are beginning to bring the sheep in for the night. Then the air takes on a heavy golden quality and we walk along the boundary with the dogs to Breezers, the pub at the bottom of the farm, in time to watch the egrets come in from the Zambezi to roost.

Before it is quite dark—“You don’t want to bump into a bloody hippo,” Dad says—we meander back up to the Tree of Forgetfulness, agreeably drunk. Mr. Zulu, a couple of his wives and several of his children are sitting on their veranda as we pass. Mr. Zulu nods a greeting and we exchange brief pleasantries. “Good evening, Mr. Zulu.” “Yes, Mr. Fuller.” His dogs mock-charge our dogs, which provokes Isabelle and Attatruk (Mum’s turkeys) into hysterical gobbling, and then Lightning begins to bray (Flash died of sleeping sickness a few years ago). “It’s quite like the musicians of Bremen,” Mum says happily.

BEFORE SUPPER—my parents take the last meal of the day late, like Europeans—Mum makes for her bath with a glass of wine. Dad and I pour ourselves a drink under the Tree of Forgetfulness and play a languid game of twos and eights. “It’s not nearly as much fun without Van here to cheat,” I say. The dogs split themselves among laps, beds and chairs across the camp and begin to lick themselves. From the bathroom we can hear Mum drowning out Luciano Pavarotti. “Ah! Il mio sol pensier sei tu, Tosca, sei tu!” There is the occasional plop of an inattentive gecko falling from the rafters in the kitchen, where Big H has made a dish of turmeric rice to go with Mum’s fish curry bubbling gently in one of the Le Creuset pots. All is as domestically blissful as it can get.

Suddenly the three dogs in the guest cottage start a loud, hysterical chorus of barking. It’s been years since I’ve heard that particular bark, but I recognize it instantly. I put my cards down and look at Dad. “That’s a snake bark,” I say.

Dad takes his pipe out of his mouth and cocks his head, listening. “Oh bloody hell, you’re right,” he says. He hurries up the steps and I follow, hoping to look supportive, while also trying to ensure that I don’t get to the door first. Dad walks into the guesthouse. “Okay, Bobo,” he says, putting up a hand. I look down. He has just stepped over a beautifully patterned snake with a diamond-shaped head, as thick as a strong man’s forearm—a puff adder. Puff adders kill more people than any other snake on the continent; their preferred diet is rodents and frogs (of which the Tree of Forgetfulness is an endlessly, self-replenishing buffet) and they strike from an S position so that they can hit a target at almost any angle. This one is in an S position now.

“Fetch Emmanuel,” Dad says.

“A manual?” I repeat, my mind racing with the possibilities—

The Care and Prevention of Snakebite

, perhaps; or

Where There Is No Doctor

.

“Yes,” Dad says. “First house on your left as you leave the yard.”

So with Mum still singing her opera—“Vittoria! Vittoria! L’alba vindice appar”—I run under the brick archway at the top of the camp and into the pitch-dark Zambezi Valley night yelling for Emmanuel like a crazed missionary, “Emmanuel! Emmanuel!” And it occurs to me that this could very well be our triple obituary: Dad bitten to death by a puff adder; Mum drowned drunk in the bath listening to Puccini; me fallen into the dark and raptured into heaven while yelling for the Messiah. I imagine Vanessa at our mass funeral saying, “Well, this is bloody typical, isn’t it?”