Collected Essays (71 page)

Authors: Rudy Rucker

Age 24, studying P. J. Cohen's book on set theory with William Burroughs in the background.

My doctoral work was in set theory, the branch of mathematical logic which deals with different levels of infinity. I delighted in studying this field as to me it felt like mathematical theology—and I still had my fascination with mysticism. This interest was brought to a head on Memorial Day in 1970, when a friend appeared at our doorstep with a dose of LSD for me. He himself had taken the drug the day before, and hadn’t enjoyed the effects. But despite his warning, I took my medicine, eager to be a true part of the Sixties. There was no evading the ego-death. My mind blew like an overamped light-bulb, and I was immersed in white light. God. The One. “I’m always here, Rudy,” a voice told me. “I’ll always love you.” I never really recovered from that experience—and I mean this in a good way. For one thing, my fear of death was greatly reduced.

There wasn’t much point taking psychedelics again. Although I made one or two half-hearted attempts, drugs would never again get me to that same place of transcendent illumination. But I’m expecting to see the White Light again on my death bed.

Another big Sixties thing was the politics. Our elected government was very seriously bent on sending me and my friends to die in Viet Nam. What with a student deferment, a fortunate lottery number, and a faked asthma attack, I didn’t find it terribly hard to dodge the draft. And of course that made me a traitor and a bad citizen. It broke my heart to see less-fortunate guys my age being slaughtered. Underground comics seemed perfectly to capture the doomed, drugged spirit of the day. I was a passionate devotee of

Zap Comix

and the work of R. Crumb. With the government out to kill us, there seemed no longer any reason to be civil or respectful towards the establishment’s values.

The high point of my graduate studies at Rutgers had to do with the campus’s proximity to Princeton and the Institute for Advanced Study, where the reclusive genius logician Kurt Gödel was in residence. All of the most fascinating and difficult results I was studying bore Gödel’s imprint, and I thought of him as a supreme guru. I was doing some interesting, although not earth-shaking, work in set theory, and I’d given a talk at Rutgers on a recent unpublished manuscript of Gödel’s that purported to solve the century old Cantor’s Continuum Problem about different degrees of infinity.

My thesis adviser Erik Ellentuck was visiting at the Institute, and I was attending a set theory seminar there. I’d applied for a post-doctorate position at the Institute, and Gödel invited me to come in for a conversation with him. Meeting Gödel was a very big deal for me, a blessing, a stroke of good fortune—the initiate’s journey to the Master’s cave. I’ve never since been in the presence of so overwhelmingly great a mind. I wrote in some detail about our encounters in my non-fiction book

Infinity and the Mind

, and Gödel inspired the character G. Kurtowski in my novel

Spacetime Donuts

.

Two effects of meeting Gödel were that I was emboldened to take mystical philosophy quite seriously and that I began studying Einstein’s work on relativity theory—Gödel had interests in both these fields. Gödel strongly believed that the perceived passage of time is an illusion, that we are in fact eternal patterns in spacetime. Like my vision of the White Light, this teaching also reduced my anxiety about death.

Although Gödel enjoyed talking with me, and let me visit him again, I didn’t get a post-doc at the Institute. I was bitterly disappointed. And finding a teaching job proved difficult. My thesis work, although publishable, wasn’t compelling enough to land me a position as a high-powered logician; and for more general kinds of teaching jobs, my expertise in the rarified field of mathematical logic was not an asset. I received exactly one job offer: assistant professor of mathematics at what was then called the State University College at Geneseo, New York.

In 1972, Sylvia and I settled into Geneseo with our two young children, and soon we were blessed with Isabel, our third child. Initially we rented a small house at 41 Oak Street, which would later be a setting for my novel

White Light

. The costs of living were low enough that we could live off my salary, with Sylvia spending most of her time with the kids. In some ways this was a difficult time for her—filled with isolation and chores. In other ways it was a good time; the children were wonderful to be with, and she got deeply involved in painting. Sylvia developed a special sharp-edged, cartoony style, colored in warm tones. We were proud when she had a hanging of her works in one of the local business’s windows. The college-town aspect of tiny Geneseo meant that we had a full social life, with none of our new friends living more than two or three blocks away.

One of the courses I taught at Geneseo was called Foundations of Geometry. The standard textbooks for the course seemed boring to me, and I developed the notion of writing up my own notes on the fourth dimension to use as a text. I think that, having spent five years studying mathematical logic and the related philosophical field known as the foundations of mathematics, the word “Foundations” in the course title served like a checkered flag to me, a signal to start my engine and step on the gas.

I’d first heard about the fourth dimension in high-school from my friend Niles, who lent me a library copy of Edwin Abbott’s

Flatland

. As chance would have it, Pop bought me a copy of this same book in paperback at the Swarthmore drugstore at the start of my freshman year. I’d read a number of science-fiction stories that mentioned the fourth dimension—I think particularly of the classic mathematical SF tales that appeared in the Clifton Fadiman-edited volumes

Fantasia Mathematica

and

The Mathematical Magpie

. Under Gödel’s influence, I’d been reading books on relativity theory. And I was wondering how to reconcile the notion of the fourth dimension as an odd unknown spatial direction with the notion of the fourth dimension as time. While at Rutgers, I’d begun trying to work out some ideas about the fourth dimension in a special notebook, mostly by means of drawings. I recall showing my 4D notes to my father. He was puzzled. “Where are you going with this?”

In the period 1973 to 1976, I expanded and rewrote my 4D notes to use as handouts for the Foundations of Geometry course, under the working title,

Geometry and Reality

. At first I mimeographed the notes for the students, and then, as I got more organized, I had the Geneseo bookstore photo-offset the notes and sell them as a text. The students seemed to enjoy my little volume, so I showed it to some of the textbook salesmen who haunt a professor’s office.

Their companies deemed my book too quirky, too popularized, too untextbooklike. But now I’d gotten the publishing blood-lust. I hit on the idea of sending my book off to the publisher that was keeping in print so many of the esoteric mathematical and philosophical books that I enjoyed: Dover Books. Back in Louisville, Mom had regularly ordered Dover books for me on all sorts of obscure topics.

Dover quickly agreed to publish my book, suggesting only that I give it a title more indicative of the contents. So it became

Geometry, Relativity and the Fourth Dimension

. Eager to cloak my shaggy young self with academic respectability, I identified myself to my unseen editors as “Professor Rudolf v. B. Rucker.” They paid me, I believe, a thousand dollars for perpetual rights to publish the book. This struck me as real money. Although I was also getting a couple of my set theory papers in print, academic publishing was slow going, with no sense of there being an actual readership, and with no checks in the mail. The idea of being paid to write popular science books seemed very good to me.

Shortly after

Geometry, Relativity and the Fourth Dimension

was published, a woman editor from Dover turned up at my door. She was in Geneseo to deliver one of her children to the college. She was surprised how young I was; the “Rudolf v. B. Rucker” ruse had convinced the Dover editors that I must be an aging, German-accented scholar. We had a good laugh, and she remarked that mine was one of the few non-public-domain books that Dover was publishing. “We have a saying at Dover,” she said. “The only good author is a dead author.”

I’d never lost sight of my dream of being a literary author, and all the while in Geneseo I was writing poems, my way of wading into the field. David Kelly, a poet-in-residence at SUNY Geneseo was an encouraging influence. We often partied together in traditional bohemian style. Another influence during this period was the poetry of Anselm Hollo, whom Greg had told me about. I never bothered sending my poems out to magazines, but I’d join in the periodic faculty poetry readings, handing out my works in mimeographed form.

In 1976, Sylvia and I went to see the Rolling Stones play outdoors at the Rich Stadium in Buffalo, New York. It was the Stones’s Bicentennial Tour. Given that the Stones have been touring ever since, it’s a little hard to remember how important they seemed back then, how of-the-moment, how radical. I almost wept to see Mick and Keith in person—two leaders I was willing to follow, two public figures in whom I could believe. The day after the concert I was so energized that I sat down at my red IBM Selectric typewriter and started writing a beatnik science fiction novel:

Spacetime Donuts

.

I composed the book in the style of my father telling a story after a meal: I made it up as I went along. But I had a particular science idea to present, and this guided my journey. The idea was that if you shrank to a small enough size, you’d end up being bigger than our galaxy. The notion of finding galaxies within our atoms is of course something of a cliché. But my notion of bending the size scale into a circle was more unexpected. I hesitate to say that I was the

first

to suggest the notion of circular scale as, over the years, I’ve found that essentially every possible idea can be found somewhere in a pre-existing piece of genre science fiction—the corpus of SF is our own homegrown Library of Babel.

Spacetime Donuts

included another element, the notion of a cadre of people able to plug their minds directly into their society’s Big Computer. This in some ways prefigured William Gibson’s epochal novel

Neuromancer

, in which console cowboys jack their brains into a planetary computer net called cyberspace. Another overlap with what came to be called cyberpunk SF was that the characters of

Spacetime Donuts

took drugs, had sex, listened to rock and roll, and were enemies of the establishment. The early sections of

Spacetime Donuts

were loosely based on my experiences in graduate school, and the hero’s love interest was modeled on Sylvia.

I was initially unable to sell

Spacetime Donuts

as a book, but there was a new SF magazine called

Unearth

which was willing to serialize it. And so I was off and running as a real science fiction writer. It was an incredible rush to see my name on the lurid cover of a digest-sized pulp magazine.

The economy was in a recession at this time, and Geneseo was eager to eliminate faculty positions. Some of the senior math faculty disliked me—I probably had the longest hair of any professor on campus; I’d allied myself with our chairman, who was embroiled in a losing departmental power struggle; and I had a bad habit of too openly speaking my mind. The fact that my Geometry course notes were being published as a book gained me no traction, and my fledgling science-fiction success was but a provocation. In 1978, I was out of my first job.

Providentially, I was offered a visiting position at the Mathematics Institute at the University of Heidelberg, funded by a grant from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation. I was perpetually applying for grants in those days, and this one happened to score. My research was to be on the same Cantor’s Continuum Problem that I’d discussed with Kurt Gödel.

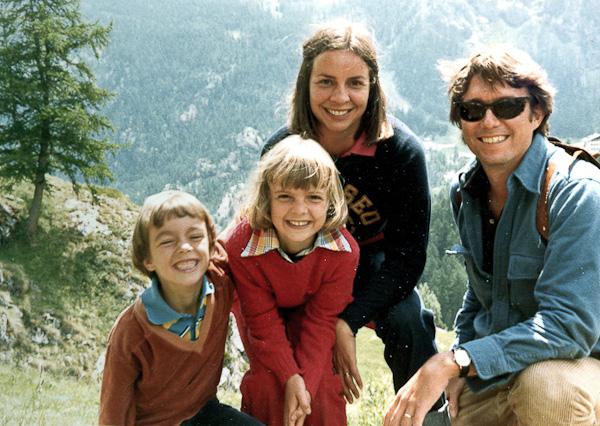

Age 33, in Zermatt with Sylvia, son Rudy and daughter Georgia.

So Sylvia, Georgia, Rudy, Isabel and I decamped to Germany. We were anxious; I remember Georgia asking me, “Do they have Halloween in Germany?” and I told her, “

Every

day is Halloween in Germany.” In a kidding way, of course, not in a mean way. I liked pretending to trick the kids, and letting them figure out the joke. For instance, later, when we lived in Lynchburg, I told them that Jerry Lewis and Jerry Falwell were the same man, only wearing different makeup and clothes. I loved hanging around with the kids, talking with them, sharing in their wonderfully fresh view of things, getting down on their level. To me, they were better company than grown-ups.

When we got to Germany, it turned out that Gert Müller, my grant supervisor, was very

laissez-faire

. He gave me a nice quiet office in the modern building of the Mathematics Institute and told me to do whatever I liked. I worked away on Cantor’s Continuum Problem for a few months, reading most of Cantor’s philosophical writings in German. But sometime early in 1979 I despaired of making any mathematical progress and wrote the novel

White Light

instead. And I gave it a subtitle lifted from a paper by Kurt Gödel:

What is Cantor’s Continuum Problem?

As I recall, I started writing the book in longhand while I was alone with the kids for a long weekend, with Sylvia visiting relatives in Budapest.