Collected Essays (69 page)

Authors: Rudy Rucker

“What do you want to be when you grow up?” the landowner asked me.

“A businessman,” I replied, wanting to be like my father. He seemed to get a lot of pleasure out of his ever-changing small companies, all of them related to wood. One of them—the Rucker Corporation—had gone bankrupt the year before, but Pop had already put together a new company called Champion Wood Products.

“Oh, don’t be a businessman, Rudy,” said Pop. “You can do better than that. You’re

bright

.”

“Then I’ll be a scientist,” I said.

As a boy, my absolute favorite reading materials were the Carl Barks

Donald Duck

and

Uncle Scrooge

comic books. Once a week I’d accompany my mother to the A & P Supermarket, and she’d give me a nickel for a comic. I loved the irreverence of the characters and the energetic, abbreviated way in which the story hopped from one frame to the next. When grown-ups would ask me how it was that I knew the meaning of some fancy word I might use, I enjoyed telling them I’d learned it from

Donald Duck

.

Every Christmas morning, my mother would arrange a fan of books around the base of the tree for me and big brother Embry. Some of the books were science fiction.

I recall being absorbed by Lee Sutton’s

Venus Boy

, Andre Norton’s

Star Man’s Son 2250 A.D.

, and a half dozen Robert Heinlein books, including

Door Into Summer

and

Revolt in 2100

. Embry was less interested in science fiction than I, but my neighbor and best friend Niles Schoening shared my fascination. We regularly went to the downtown Louisville Free Public Library to pore over their SF holdings—which filled but a single shelf. I remember marveling over the riches to be found in books with titles like

The Best Science Fiction of 1949

.

When we were fourteen or fifteen, Niles and I discovered beer, Zen Buddhism, and the beatniks. Jack Kerouac’s

On the Road

spoke to me like nothing I’d ever read before. To be out in the world, free as a bird, drinking, smoking, meeting women and yakking all night about God—yes!

Brother Embry was more an aficionado of the juvenile delinquent and hot-rodder culture. He souped up a series of Model A and Model T Fords purchased from farmers who had them in their barns. But he was interested in the beats as well. Niles and I found a set of bongos, copies of

Dig

magazine, and dozens of back issues of

Evergreen Review

in Embry’s basement lair.

These were the old digest-sized issues of

Evergreen Review

. Raw youth that I was, I initially combed through them in search of titillation. Instead I found excerpts of William Burroughs’s

Naked Lunch

, poems by Allen Ginsberg and, somehow the most heartening, story after story by Beat unknowns. Men and women writing about their daily routines as if life itself were strange and ecstatic. I wanted to be a beatnik.

When I was fifteen, Embry and I were in the back yard playing with our rusty old swing set—seeing who could jump the furthest. The chain of the swing broke; I flew through the air and landed badly, rupturing my spleen. Oddly enough, I

knew

it was my spleen, as I’d recently been studying a paperback book on karate. The pain in my side was at the location marked “spleen” on my book’s vulnerability chart. The surgeon, a family friend, never got over the fact that little Rudy Rucker had known he’d hurt his spleen.

Although I didn’t realize it till years later, I would have died of internal bleeding in less than an hour if my father hadn’t rushed me to the hospital to have my spleen removed. Experiencing the anesthetic was very strange—going from the light into the dark and back into the light. It set me to thinking about the fact that one of these days I’d become unconscious for good.

Bam

and then—nothing.

While I was in the hospital, my mother brought me a paperback copy of

Untouched By Human Hands

, a collection of science fiction stories by Robert Sheckley. Somewhere Vladimir Nabokov writes about the “initial push that sets the heavy ball rolling down the corridors of years,” and for me the push was Sheckley’s book. I thought it was the coolest thing I’d ever seen, and I knew in my heart of hearts that my greatest ambition was to become a science fiction writer. Sheckley’s work was masterful, and it had a jokey edge that—to my mind—set it above the more straightforward work of the other SF writers. Most of all, there was something about his style that gave me a sense that I could do it myself. He wrote like I thought.

And thus, in later years, I became a beatnik-influenced science fiction writer with a cartoony, humorous edge.

I was born near Louisville on March 22, 1946—the singular cusp of the zodiac, where the world snake bites its tail.

My earliest memory is of fingerpainting the white expanse of my bed’s footboard with the contents of my diaper. I didn’t yet know it smelled bad. I remember the morning sun slanting in, my mother appearing behind me, her cry of dismay.

Marianne von Bitter Rucker, around 1970.

Marianne von Bitter was from Berlin, a slender aristocratic woman resembling Marlene Dietrich with brown hair. Everyone called her Nonny. She and my father met when she came to study at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia. This was in 1937. My mother’s father, Rudolf von Bitter, could sense the gathering storm, and he was happy to get his only daughter out of harm’s way. Somewhere higher up in the branches of Rudolf von Bitter’s family tree were a few Jews, and there was a sense that if the Nazis stayed in power long enough, they’d get around to him and his family. At least Nonny, his youngest child, would be safe in America.

Also to be found among my German grandfather’s ancestors was the famous philosopher Georg Hegel. I remember the relationship under the rubric, “three greats,” that is, I’m Hegel’s great-great-great-grandson. When my mother left Berlin, she brought with her Hegel’s schoolboy diary—a treasured family memento. Written mostly in Latin, the little book covers the period 1785 to 1787, when Hegel was fifteen to seventeen years old. Eventually my mother lent it to some scholars who translated it into German. In my favorite passage, Hegel is excited about a rumor among the local peasants that an army of dead souls had ridden by the night before. Shades of a UFO sighting! As it turns out, the peasants had been deceived by the lights of passing carriages from a late party.

My mother was opinionated, outspoken within the family, and quick to label things “amazing” or “disgusting”—two of her favorite words. But she was always patient and loving with me, always approving. One of her most characteristic gestures towards me was to smile and then nod encouragingly.

When I was in the first few grades of school, I’d come home and it would be just the two of us there for lunch together. She’d eat square pumpernickel bread and blue cheese, while I preferred Campbell’s soup and perhaps a bologna sandwich. After lunch I’d sit on Mom’s lap and she’d hug me. “Yes,” Mom would say. “Good Rudy.” Our dog Muffin would whine, wanting to get some hugs too.

My father, Embry Cobb Rucker, Sr., was descended from Peter Rucker, a Flemish Huguenot who landed near the mouth of Virginia’s James River in 1790. The Ruckers and Cobbs were active in the South; one was a senator, another the first Governor of Georgia, and many of them owned plantations. Of course after the Civil War, all this was gone with the wind. My father’s father was a well-off insurance man.

When Pop went to college it was the Great Depression, and having the tuition in hand, his father could have sent him to any school at all, but Pop happened to choose the Virginia Military Institute, for no better reason than that another neighborhood boy had gone there.

Pop liked to regale Embry Jr. and me with horror stories of his first year at VMI. The freshmen were called rats. One rat was paddled so hard that blood could be seen seeping through the seat of this white dress pants. Another was wrapped in a mattress and thrown out of a second-story window; I believe it broke his back. Pop himself had to squat for an hour above the point of a propped-up bayonet. He seemed happy to have survived the hazing, but still a little angry about it. As a senior, he himself was so merciful to the freshmen that he was known as “Rat Daddy.” At graduation, all the rats cheered for Pop, and his father turned to the man next him and said, “That’s my boy.”

At VMI, Pop learned to shoot a pistol from a horse, lost a front tooth playing center on the football team, and lost the denture during a wild night at a notorious bordello called Lucille’s, in Lynchburg, Virginia. Once Pop was suspended for hopping onto the dining-table in the mess hall and hollering something obscene at an upperclassman who’d just finished intoning the grace in a manner that Pop found gallingly pompous. He also got a degree in Civil Engineering, despite having enormous difficulties with the obligatory class in Calculus. “I never figured out what they were talking about,” he’d always say, amazed that I’d ended up teaching the subject.

He was a great story-teller; sometimes after our Sunday dinner or evening meal, Pop would spin tales for my brother and me. The stories were always different, but they usually involved dwarves. One event would flow into the next in a logical yet unpredictable fashion. Pop prided himself on making up the stories as he went along. I learned a lesson: keep narrating and the ideas will come.

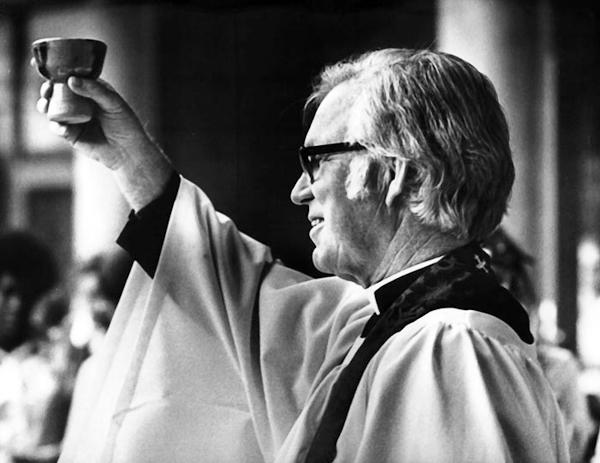

Embry Cobb Rucker, around 1970.

When Pop was forty he took it into his head to become an Episcopal minister. He covered the required course work by independent study, passed the required academic, theological and psychological exams, and was ordained, first as a deacon and then as a priest. When he was interviewed on a Louisville TV show called

Pastor’s Round Table

, and was asked why he became a minister so late in life, Pop claimed to have answered, “Well, I couldn’t make a go of anything else, so I thought I’d give this a whirl.” Although, really, his latest wood business was still bringing in a modest amount of money.

I never did understand exactly why he became a priest. He didn’t talk a lot about religion to us. But he was always committed to being kind to people, to doing good, to helping the less fortunate. One reason might be that he had a need for approval, and that he took pleasure in evoking positive feedback. But his priesthood was about more than his own needs. When he was standing at the altar, holding up the wine and the host, he’d acquire a truly numinous glow.

For her part, my mother wasn’t thrilled by this turn of events. “I

never

planned to marry a minister,” she once remarked. She was fairly shy, and felt uncomfortable when thrown together with new people. It was no joy for her to entertain parishioners whom she might find dull or tacky. But she was so charming and smart that, in the end, people always liked her. She stayed the course and did the necessary; she took good care of her husband and her two sons.

Not that her life was all about being a home-maker. She was an artist for her whole life, producing scores of paintings—mostly landscapes. In her later years, she took up pottery, turning out cartons and cartons of lovely cups, bowls and plates.

One ongoing problem was that Mom developed diabetes around 1962, and had trouble controlling the disease. She was punctilious about her insulin injections and her diet—too punctilious. Periodically her blood sugar would drop so low that she’d have frightening insulin reactions. The effect was if she’d suddenly be very drunk; we’d try and force orange juice on her, but sometimes she’d refuse it. Occasionally my father or I had to give her a glucagon injection to bring her back.

When my father turned sixty he had a heart attack and a coronary bypass operation. The technology of procedure was still crude, and it had a devastating effect on him. Overnight his personality changed. He grew distant and depressed. He’d point to the vertical scar on his chest and wince. “They opened me right up.”

Later I would model the character Cobb Anderson in my novel

Software

on Pop during this period of his life. My character Cobb is a man with a bad heart whose body is replaced by a robot copy of his flesh body, with his memories being transferred from his discarded brain to the computer mind of the robot. At first my character doesn’t even realize the transfer has taken place, but then he notices a little maintenance door in his chest.