Authors: Paul Auster

Collected Prose: Autobiographical Writings, True Stories, Critical Essays, Prefaces, Collaborations With Artists, and Interviews (49 page)

But this is not all. And the facts must be considered still further. For the day comes when he is allowed to leave the Tower. He has been freed, but he is nevertheless not free. A full pardon will be granted only on the condition that he accomplish something that is flatly impossible to accomplish. Already the victim of the basest political intrigue, the butt of justice gone berserk, he will have his last fling and create his most magnificent failure as a sadistic entertainment for his captors. Once called the Fox, he is now like a mouse in the jaws of a cat. The King instructs him: go where the Spanish have rightful claim, rob them of their gold, and do not antagonize them or incite them to retaliation. Any other man would have laughed. Accused of having conspired with the Spanish thirteen years ago and put into the Tower as a result, he is now told to do a thing in such terms that they invalidate the very charge for which he was found guilty in the first place. But he does not laugh.

One must assume that he knew what he was doing. Either he thought that he could do what he set out to do, or the lure of the new world was so strong that he simply could not resist. In any case, it hardly matters now. Everything that could go wrong for him did go wrong, and from the very beginning the voyage was a disaster. After thirteen years of solitude, it is not easy to return to the world of men, and even less so when one is old. And he is an old man now, more than sixty, and the prison reveries in which he had seen his thoughts turn into the most glorious deeds now turn to dust before his eyes. The crew rebels against him, no gold can be found, the Spanish are hostile. Worst of all: his son is killed.

Take everything away from a man, and that man will continue to exist. But the everything of one man is not that of another, and even the strongest of men will have within himself a place of supreme vulnerability. For Raleigh, this place is occupied by his son, who is at once the emblem of his greatest strength and the seed of his undoing. To all things outward, the boy will bring doom, and though he is a child of love, he remains the living proof of lust—the wild heat of a man willing to risk everything to answer the call of his body. But this lust is nevertheless love, and such a love as seldom speaks more purely of a man’s worth. For one does not cavort with a lady of the Queen unless one is ready to destroy one’s position, one’s honor, one’s name. These women are the Queen’s person, and no man, not even the most favored man, can approach or possess without royal consent. And yet, he shows no signs of contrition; he makes good on all he has done. For disgrace need not bring shame. He loves the woman, he will continue to love her, she will become the very substance of his life. And in this first, prophetic exile, his son is born.

The boy grows. And he grows wild. The father can do no more than dote and fret, prescribe warnings, be warmed by the fire of his flesh and blood. He writes an extraordinary poem of admonition to the boy, at once an ode to chance and a raging against the inevitable, telling him that if he does not mend his ways he will wind up at the end of a rope, and the boy sallies off to Paris with Ben Jonson on a colossal binge. There is nothing the father can do. It is all a question of waiting. When he is at last allowed to leave the Tower, he takes the boy along with him. He needs the comfort of his son, and he needs to feel himself the father. But the boy is murdered in the jungle. Not only does he come to the end his father had predicted for him, but the father himself has become the unwitting executioner of his own son.

And the death of the son is the death of the father. For this man will die. The journey has failed, the thought of grace does not even enter his head. England means the axe—and the gloating triumph of the King. The very wall has been reached. And yet, he goes back. To a place where the only thing that waits for him is death. He goes back when everything tells him to run for life—or to die by his own hand. For if nothing else, one can always choose one’s moment. But he goes back. And the question therefore is: why cross an entire ocean only to keep an appointment with death?

We may well speak of madness, as others have. Or we may well speak of courage. But it hardly matters what we speak. For it is here that words begin to fail. And if we ever manage to say what we want to say, it will nevertheless be said in the knowledge of this failure. All this, therefore, is speculation.

If there is such a thing as an art of living, then the man who lives life as an art will have a sense of his own beginning and his own end. And beyond that, he will know that his end is in his beginning, and that each breath he draws can only bring him nearer to that end. He will live, but he will also die. For no work remains unfinished, even the one that has been abandoned.

Most men abandon their lives. They live until they do not live, and we call this death. For death is a very wall. A man dies, and therefore he no longer lives. But this does not mean it is death. For death is only in the seeing of death, and in the living of death. And we may truly say that only the man who lives his life to the fullest of life will be able to see his own death. And we may truly say what we will say. For it is here that words begin to fail.

Each man approaches the wall. One man turns his back, and in the end he is struck from behind. Another goes blind at the very thought of it and spends his life groping ahead in fear. And another sees it from the very beginning, and though his fear is no less, he will teach himself to face it, and go through life with open eyes. Every act will count; even to the last act, because nothing will matter to him anymore. He will live because he is able to die. And he will touch the very wall.

Therefore Raleigh. Or the art of living as the art of death. Therefore England—and therefore the axe. For the subject is not only life and death. It is death. And it is life. And we may truly say what we will say.

1975

Northern Lights

The paintings of Jean-Paul Riopelle

PROGRESS OF THE SOUL

At the limit of a man, the earth will disappear. And each thing seen of earth will be lost in the man who comes to this place. His eyes will open on earth, and whiteness will engulf the man. For this is the limit of earth — and therefore a place where no man can be.

Nowhere. As if this were a beginning. For even here, where the land escapes all witness, a landscape will emerge. That is to say, there is never nothing where a man has come, even in a place where all has disappeared. For he cannot be anywhere until he is nowhere, and from the moment he begins to lose his bearings, he will find where he is.

Therefore, he goes to the limit of earth, even as he stands in the midst of life. And if he stands in this place, it is only by virtue of a desire to be here, at the limit of himself, as if this limit were the core of another, more secret beginning of the world. He will meet himself in his own disappearance, and in this absence he will discover the earth — even at the limit of earth.

THE BODY’S SPACE

There is no need, then, except the need to be here. As if he, too, could cross into life and take his stand among the things that stand among him: a single thing, even the least thing, of all the things he is not. There is this desire, and it is inalienable. As if, by opening his eyes, he might find himself in the world.

A forest. And within that forest, a tree. And upon that tree, a leaf. A single leaf, turning in the wind. This leaf, and nothing else. The thing to be seen.

To be seen: as if he could be here. But the eye has never been enough. It cannot merely see, nor can it tell him how to see. For when a single leaf turns, it is the entire forest that turns around it. And he who turns around himself.

He wants to see what is. But no thing, not even the least thing, has ever stood still for him. For a leaf is not only a leaf: it is the earth, it is the sky, it is the tree it hangs from in the light of any given hour. But it is also a leaf. That is to say, it is what moves.

It is not enough, then, simply for him to open his eyes. If he is to see, he must begin by moving toward the thing that moves. For seeing is a process that engages the entire body. And though he begins as a witness of the thing he is not, once the first step has been taken, he becomes a participant in a motion that knows no boundaries between self and object.

Distances: what the quickness of the eye discovers, the body must then follow into experience. There is this distance to be crossed, and each time it is a new distance, a different space that opens before the eye. For no two leaves are alike. Therefore, he must feel his feet on the earth: and learn, with a patience that is the instinct of breath and blood, that this same earth is the destiny of the leaf as well.

DISAPPEARANCE

He begins at the beginning. And each time he begins, it is as if he had never lived before. Painting: or the desire to vanish in the act of seeing. That is to say, to see the thing that is, and each time to see it for the first time, as if it were the last time that he would ever see.

At the limit of himself: the pursuit of the nearly-nothing. To breathe in the whiteness of the farthest north. And all that is lost, to be born again from this emptiness in the place where desire carries him, and dismembers him, and scatters him back into earth.

For when he is here, he is nowhere. And time does not exist for him. He will suffer no duration, no continuity, no history: time is merely an alternation between being and not being, and at the moment he begins to feel time passing within him, he knows that he is no longer alive. The self flares up in an image of itself, and the body traces a movement it has traced a thousand times before. This is the curse of memory, or the separation of the body from the world.

If he is to begin, then, he must carry himself to a place beyond memory. Once a gesture has been repeated, once a road has been discovered, the act of living becomes a kind of death. The body must empty itself of the world in order to find the world, and each thing must be made to disappear before it can be seen. The impossible is that which allows him to breathe, and if there is life in him, it is only because he is willing to risk his life.

Therefore, he goes to the limit of himself. And at the moment he no longer knows where he is, the world can begin for him again. But there is no way of knowing this in advance, no way of predicting this miracle, and between each lapse, in each void of waiting, there is terror. And not only terror, but the death of the world in himself.

THE ENDS OF THE EARTH

Lassitude and fear. The endless beginning of time in the body of a man. Blindness, in the midst of life; blindness, in the solitude of a single body. Nothing happens. Or rather, everything begins to be nothing. And the world is so far from him that in each thing he sees of the world, he finds nothing but himself.

Emptiness and immobility, for as long as it takes to kill him. Here, in the midst of life, where the very density of things seems to suffocate the possibility of life, or here, in the place where memory inhabits him. There is no choice but to leave. To lock his door behind him and set out from himself, even to the ends of the earth.

The forest. Or a lapse in the heart of time, as if there were a place where a man could stand. Whiteness opens before him, and if he sees it, it will not be with the eye of a painter, but with the body of a man struggling for life. Gradually, all is forgotten, but not through any act of will: a man can discover the world only because he must — and for the simple reason that his life depends on it.

Seeing, therefore, as a way of being in the world. And knowledge as a force that rises from within. For after being nowhere at all, he will eventually find himself so near to the things he is not that he will almost be within them.

Relations. That is to say, the forest. He begins with a single leaf: the thing to be seen. And because there is one thing, there can be everything. But before there is anything at all, there must be desire, and the joy of a desire that propels him toward his very limit. For in this place, everything connects; and he, too, is part of this process. Therefore, he must move. And as he moves, he will begin to discover where he is.

NATURE

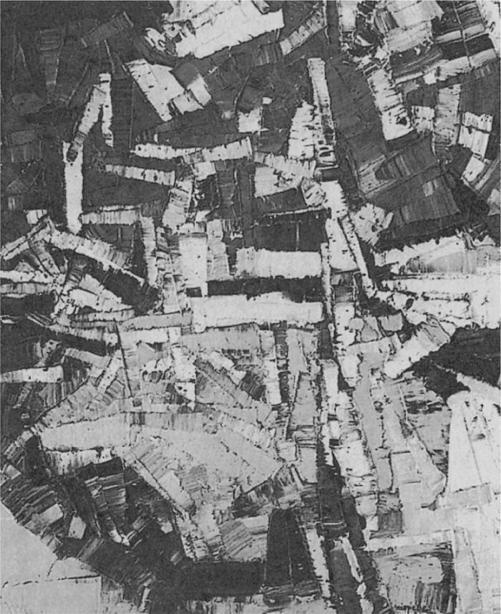

No painting captures the spirit of natural plentitude more truly than this one. Because this painter understands that the body is what sees, that there can be no seeing without motion, he is able to carry himself across the greatest distances — and come to a place of nearness and intimacy, where each thing can be set free to be what it is.

To look at one of these paintings is to enter it: to be whirled into a field of forces that is composed not only of things, but of the motion of things — of their dislocation and their harmony. For this is a man who knows the forest, and the almost inhuman energy to be found in these canvases does not speak of an abstract program to become one-with-nature, but rather, more basically, of a tangible need to be present, as if life could be lived only in the fullness of this desire. As a consequence, this work does not merely re-present the natural landscape. It is a record of an encounter, a process of penetration and mutual dependence, and, as such, a portrait of a man at the limit of himself.