Come as You Are (3 page)

Authors: Emily Nagoski

That’s actually the bad news.

The good news is that when you understand how your sexual response mechanism works, you can begin to take control of your environment and your brain in order to maximize your sexual potential, even in a broken world. And when you change your environment and your brain, you can change—and heal—your sexual functioning.

This book contains information that I have seen transform women’s sexual wellbeing. I’ve seen it transform men’s understanding of their

women partners. I’ve seen same-sex couples look at each other and say, “Oh. So

that’s

what was going on.” Students, friends, blog readers, and even fellow sex educators have read a blog post or heard me give a talk and said, “Why didn’t anyone tell me this before? It explains

everything

!”

I know for sure that what I’ve written in this book can help you. It may not be enough to heal all the wounds inflicted on your sexuality by a culture in which it sometimes feels nearly impossible for a woman to “do” sexuality right, but it will provide powerful tools in support of your healing.

How do I know?

Evidence, of course!

At the end of one semester, I asked my 187 students to write down one really important thing they learned in my class. Here’s a small sample of what they wrote:

I am normal!

I AM NORMAL

I learned that everything is NORMAL, making it possible to go through the rest of my life with confidence and joy.

I learned that I am normal! And I learned that some people have spontaneous desire and others have responsive desire and this fact helped me really understand my personal life.

Women vary! And just because I do not experience my sexuality in the same way as many other women, that does not make me abnormal.

Women’s sexual desire, arousal, response, etc., is incredibly varied.

The one thing I can count on regarding sexuality is that people vary, a lot.

That everyone is different and everything is normal; no two alike.

No two alike!

And many more. More than half of them wrote some version of “I am normal.”

I sat in my office and read those responses with tears in my eyes. There was something urgently important to my students about feeling “normal,” and somehow my class had cleared a path to that feeling.

The science of women’s sexual wellbeing is young, and there is much still to be learned. But this young science has already discovered truths about women’s sexuality that have transformed my students’ relationships with their bodies—and it has certainly transformed mine. I wrote this book to share the science, stories, and sex-positive insights that prove to us that, despite our culture’s vested interest in making us feel broken, dysfunctional, unlovely, and unlovable, we are in fact fully capable of confident, joyful sex.

• • •

The promise of

Come as You Are

is this: No matter where you are in your sexual journey right now, whether you have an awesome sex life and want to expand the awesomeness, or you’re struggling and want to find solutions, you will learn something that will improve your sex life and transform the way you understand what it means to be a sexual being. And you’ll discover that, even if you don’t yet feel that way, you are already sexually whole and healthy.

The science says so.

I can prove it.

I

. I’ll use “they” as a singular pronoun, rather than “he or she” throughout the book. It’s simpler, as well as more inclusive of folks outside the gender binary.

part 1

the (not-so-basic) basics

one

anatomy

NO TWO ALIKE

Olivia likes to watch herself in the mirror when she masturbates.

Like many women, Olivia masturbates lying on her back and rubbing her clitoris with her hand. Unlike many women, she props herself up on one elbow in front of a full-length mirror and watches her fingers moving in the folds of her vulva.

“I started when I was a teenager,” she told me. “I had seen porn on the Internet, and I was curious about what I looked like, so I got a mirror and started pulling apart my labia so I could see my clit, and what can I say? It felt good, so I started masturbating.”

It’s not the only way she masturbates. She also enjoys the “pulse” spray on her showerhead, she has a small army of vibrators at her command, and she spent several months teaching herself to have “breath” orgasms, coming without touching her body at all.

This is the kind of thing women tell you when you’re a sex educator.

She also told me that looking at her vulva convinced her that her sexuality was more like a man’s, because her clitoris is comparatively large—“like a baby carrot, almost”—which, she concluded, made her more masculine; it must be bigger because she had more testosterone, which in turn made her a horny lady.

I told her, “Actually there’s no evidence of a relationship between an adult woman’s hormone levels, genital shape or size, and sexual desire or response.”

“Are you sure about that?” she asked.

“Well, some women have ‘testosterone-dependent’ desire,” I said, pondering, “which means they need a certain very low minimum of T, but that’s not the same as ‘high testosterone.’ And the distance between the clitoris and the urethra predicts how reliably orgasmic a woman is during intercourse, but that’s a whole other thing. I’d be fascinated to see a study that directly asked the question, but the available evidence suggests that variation in women’s genital shapes, sizes, and colors doesn’t predict anything in particular about her level of sexual interest.”

“Oh,” she said. And that single syllable said to me: “Emily, you have missed the point.”

Olivia is a psychology grad student—a former student of mine, an activist around women’s reproductive health issues, and now doing her own research, which is how we got started on this conversation—so I got excited about the opportunity to talk about the science. But with that quiet, “Oh,” I realized that this wasn’t about the science for Olivia. It was about her struggle to embrace her body and her sexuality just as it is, when so much of her culture was trying to convince her there is something wrong with her.

So I said, “You know, your clitoris is totally normal. Everyone’s genitals are made of all the same parts, just organized in different ways. The differences don’t necessarily mean anything, they’re just varieties of beautiful and healthy. Actually,” I continued, “that could be the most important thing you’ll ever learn about human sexuality.”

“Really?” she asked. “Why?”

This chapter is the answer to that question.

Medieval anatomists called women’s external genitals the “pudendum,” a word derived from the Latin

pudere

, meaning “to make

ashamed.” Our genitalia were thus named “from the shamefacedness that is in women to have them seen.”

1

Wait:

what

?

The reasoning went like this: Women’s genitals are tucked away between their legs, as if they wanted to be hidden, whereas male genitals face forward, for all to see. And why would men’s and women’s genitals be different in this way? If you’re a medieval anatomist, steeped in a sexual ethic of purity, it’s because: shame.

Now, if we assume “shame” isn’t really why women’s genitals are under the body—and I hope it’s eye-rollingly obvious that it’s not—why, biologically, are male genitals in front and female genitals underneath?

The answer is, they’re actually not! The female equivalent to the penis—the clitoris—is positioned right up front, in the equivalent location to the penis. It’s less obvious than the penis because it’s smaller—and it’s smaller not because it’s shy or ashamed, but because females don’t have to transport our DNA from inside our own bodies to inside someone else’s body. And the female equivalent of the scrotum—the outer labia—is also located in very much the same place as the scrotum, but because the female gonads (the ovaries) are internal, rather than external like the testicles, the labia don’t extend much past the body, so they’re less obvious. Again, the ovaries are not internal because of shame, but because we’re the ones who get pregnant.

In short, female genitals appear “hidden” only if you look at them through the lens of cultural assumptions rather than through the eyes of biology.

We’ll see this over and over again throughout the book: Culture adopts a random act of biology and tries to make it Meaningful, with a capital “Mmmh.” We metaphorize genitals, seeing what they are like rather than what they are, we superimpose cultural Meaning on them, as Olivia superimposed the meaning of “masculine” on her largish clitoris, to conclude that her anatomy had some grand meaning about her as sexually masculine.

When you can see your body as it is, rather than what culture proclaims it to Mean, then you experience how much easier it is to live with and love your genitals, along with the rest of your sexuality, precisely as they are.

So in this chapter, we’ll look at our genitals through biological eyes, cultural lenses off. First, I’ll walk you through the ways that male and female genitals are made of exactly the same parts, just organized in different ways. I’ll point out where the biology says one thing and culture says something else, and you can decide which makes more sense to you. I’ll illustrate how the idea of all the same parts, organized in different ways extends far beyond our anatomy to every aspect of human sexual response, and I’ll argue that this might be the most important thing you’ll ever learn about your sexuality.

In the end, I’ll offer a new central metaphor to replace all the wacky, biased, or nonsensical ones that culture has tried to impose on women’s bodies. My goal in this chapter is to introduce an alternative way of thinking about your body and your sexuality, so that you can relate to your body on its own terms, rather than on terms somebody else chose for you.

the beginning

Imagine two fertilized eggs that have just implanted in a uterus. One is XX—genetically female—and the other is XY—genetically male. Fraternal twins, a sister and a brother. Faces, fingers, and feet—the siblings will develop all the same body parts, but the parts will be organized differently, to give them the individual bodies that will be instantly distinguishable from each other as they grow up. And just as their faces will each have two eyes, one nose, and a mouth, all arranged in more or less the same places, so their genitals will have all the same basic elements, organized in roughly the same way. But unlike their faces and fingers and feet, their genitals will develop before birth into configurations that their parents will automatically recognize as male or female.

All the same parts, organized in different ways.

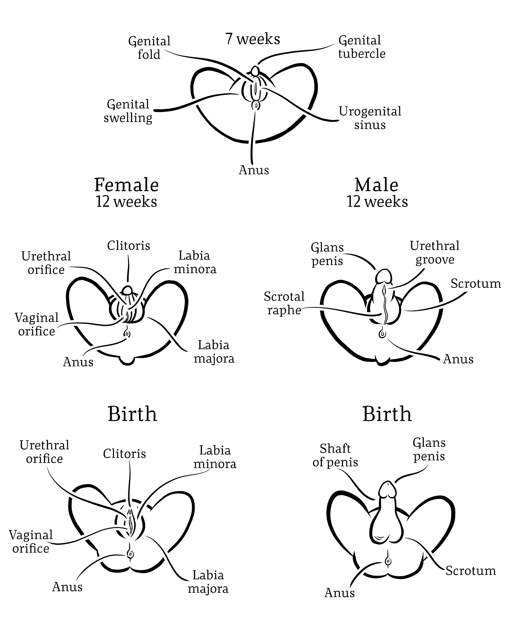

Every body’s genitals are the same until six weeks into gestation, when the universal genital hardware begins to organize itself into either the female configuration or the male configuration.

Here’s how it happens. About six weeks after the fertilized egg implants in the uterus, there is a wash of masculinizing hormones. The male

blastocyst (a group of cells that will form the embryo) responds to this by developing its “prefab” universal genital hardware into the male configuration of penis, testicles, and scrotum. The female blastocyst does not respond to the hormone wash at all, and instead develops its prefab universal genital hardware into the default, female configuration of clitoris, ovaries, and labia.

Welcome to the wonderful world of biological homology.

Homologues are traits that have the same biological origins, though they may have different functions. Each part of the external genitalia has a homologue in the other sex. I’ve mentioned two of them already: Both male and female genitals have a round-ended, highly sensitive, multichambered organ to which blood flows during sexual arousal. On females, it’s the clitoris; on males, it’s the penis. And each has an organ that is soft, stretchy, and grows coarse hair after puberty. On females, it’s the outer lips (labia majora); on males, it’s the scrotum. These parts don’t just look superficially alike; they are developed from the equivalent fetal tissue. If you look closely at a scrotum, you’ll notice a seam running up the center—the scrotal raphe. That’s where his scrotum would have split into labia if he had developed female genitals instead.