Complete Works of Henrik Ibsen (113 page)

Read Complete Works of Henrik Ibsen Online

Authors: Henrik Ibsen

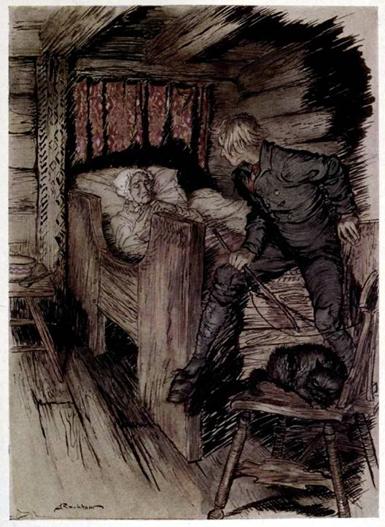

[ÅSE’s room. Evening. The room is lighted by a wood fire on the open hearth. A cat is lying on a chair at the

foot of the bed.]

[ÅSE lies in the bed, fumbling about restlessly with her hands on the coverlet.]

ÅSE

Oh, Lord my God, isn’t he coming?

The time drags so drearily on.

I have no one to send with a message;

and I’ve much, oh so much, to say.

I haven’t a moment to lose now!

So quickly! Who could have foreseen!

Oh me, if I only were certain

I’d not been too strict with him!

PEER GYNT

[enters]

Good evening!

ÅSE

The Lord give you gladness!

You’ve come then, my boy, my dear!

But how dare you show face in the valley?

You know your life’s forfeit here.

PEER

Oh, life must e’en go as it may go;

I felt that I must look in.

ÅSE

Ay, now Kari is put to silence,

and I can depart in peace!

PEER

Depart? Why, what are you saying?

Where is it you think to go?

ÅSE

Alas, Peer, the end is nearing;

I have but a short time left.

PEER

[writhing, and walking towards the back of the room]

See there now! I’m fleeing from trouble;

I thought at least here I’d be free — !

Are your hands and your feet a-cold, then?

ÅSE

Ay, Peer; all will soon be o’er. —

When you see that my eyes are glazing,

you must close them carefully.

And then you must see to my coffin;

and be sure it’s a fine one, dear.

Ah no, by-the-bye —

PEER

Be quiet!

There’s time yet to think of that.

ÅSE

Ay, ay.

[Looks restlessly around the room.]

Here you see the little

they’ve left us! It’s like them, just.

PEER

[with a writhe]

Again!

[Harshly.]

Well, I know it was my fault.

What’s the use of reminding me?

ÅSE

You! No, that accursed liquor,

from that all the mischief came!

Dear my boy, you know you’d been drinking;

and then no one knows what he does;

and besides, you’d been riding the reindeer;

no wonder your head was turned!

PEER

Ay, ay; of that yarn enough now.

Enough of the whole affair.

All that’s heavy we’ll let stand over

till after — some other day.

[Sits on the edge of the bed.]

Now, mother, we’ll chat together;

but only of this and that, —

forget what’s awry and crooked,

and all that is sharp and sore. —

Why see now, the same old pussy;

so she is alive then, still?

ÅSE

She makes such a noise o’ nights now;

you know what that bodes, my boy!

The Death of Aas

PEER

[changing the subject]

What news is there here in the parish?

ÅSE

[smiling]

There’s somewhere about, they say,

a girl who would fain to the uplands —

PEER

[hastily]

Mads Moen, is he content?

ÅSE

They say that she hears and heeds not

the old people’s prayers and tears.

You ought to look in and see them; —

you, Peer, might perhaps bring help —

PEER

The smith, what’s become of him now?

ÅSE

Don’t talk of that filthy smith.

Her name I would rather tell you,

the name of the girl, you know —

PEER

No, now we will chat together,

but only of this and that, —

forget what’s awry and crooked,

and all that is sharp and sore.

Are you thirsty? I’ll fetch you water.

Can you stretch you? The bed is short.

Let me see; — if I don’t believe, now,

It’s the bed that I had when a boy!

Do you mind, dear, how oft in the evenings

you sat at my bedside here,

and spread the fur-coverlet o’er me,

and sang many a lilt and lay?

ÅSE

Ay, mind you? And then we played sledges

when your father was far abroad.

The coverlet served for sledge-apron,

and the floor for an ice-bound fiord.

PEER

Ah, but the best of all, though, —

mother, you mind that too? —

the best was the fleet-foot horses —

ÅSE

Ay, think you that I’ve forgot? —

It was Kari’s cat that we borrowed;

it sat on the log-scooped chair —

PEER

To the castle west of the moon, and

the castle east of the sun,

to Soria-Moria Castle

the road ran both high and low.

A stick that we found in the closet,

for a whip-shaft you made it serve.

ÅSE

Right proudly I perked on the box-seat —

PEER

Ay, ay; you threw loose the reins,

and kept turning round as we travelled,

and asked me if I was cold.

God bless you, ugly old mother, —

you were ever a kindly soul — !

What’s hurting you now?

ÅSE

My back aches,

because of the hard, bare boards.

PEER

Stretch yourself; I’ll support you.

There now, you’re lying soft.

ÅSE

[uneasily]

No, Peer, I’d be moving!

PEER

Moving?

ÅSE

Ay, moving; ‘tis ever my wish.

PEER

Oh, nonsense! Spread o’er you the bed-fur.

Let me sit at your bedside here.

There; now we’ll shorten the evening

with many a lilt and lay.

ÅSE

Best bring from the closet the prayer-book:

I feel so uneasy of soul.

PEER

In Soria-Moria Castle

the King and the Prince give a feast.

On the sledge-cushions lie and rest you;

I’ll drive you there over the heath —

ÅSE

But, Peer dear, am I invited?

PEER

Ay, that we are, both of us.

[He throws a string round the back of the chair on which the cat is lying, takes up a stick, and seats

himself at the foot of the bed.]

Gee-up! Will you stir yourself, Black-boy?

Mother, you’re not a-cold?

Ay, ay; by the pace one knows it,

when Grane begins to go!

ÅSE

Why, Peer, what is it that’s ringing — ?

PEER

The glittering sledge-bells, dear!

ÅSE

Oh, mercy, how hollow it’s rumbling!

PEER

We’re just driving over a fiord.

ÅSE

I’m afraid! What is that I hear rushing

and sighing so strange and wild?

PEER

It’s the sough of the pine-trees, mother,

on the heath. Do you but sit still.

ÅSE

There’s a sparkling and gleaming afar now;

whence comes all that blaze of light?

PEER

From the castle’s windows and doorways.

Don’t you hear, they are dancing?

ÅSE

Yes.

PEER

Outside the door stands Saint Peter,

and prays you to enter in.

ÅSE

Does he greet us?

PEER

He does, with honor,

and pours out the sweetest wine.

ÅSE

Wine! Has he cakes as well, Peer?

PEER

Cakes? Ay, a heaped-up dish.

And the dean’s wife is getting ready

your coffee and your dessert.

ÅSE

Oh, Christ; shall we two come together?

PEER

As freely as ever you will.

ÅSE

Oh, deary, Peer, what a frolic

you’re driving me to, poor soul!

PEER

[cracking his whip]

Gee-up; will you stir yourself, Black-boy!

ÅSE

Peer, dear, you’re driving right?

PEER

[cracking his whip again]

Ay, broad is the way.

ÅSE

This journey,

it makes me so weak and tired.

PEER

There’s the castle rising before us;

the drive will be over soon.

ÅSE

I will lie back and close my eyes then,

and trust me to you, my boy!

PEER

Come up with you, Grane, my trotter!

In the castle the throng is great;

they bustle and swarm to the gateway.

Peer Gynt and his mother are here!

What say you, Master Saint Peter?

Shall mother not enter in?

You may search a long time, I tell you,

ere you find such an honest old soul.

Myself I don’t want to speak of;

I can turn at the castle gate.

If you’ll treat me, I’ll take it kindly;

if not, I’ll go off just as pleased.

I have made up as many flim-flams

as the devil at the pulpit-desk,

and called my old mother a hen, too,

because she would cackle and crow.

But her you shall honour and reverence,

and make her at home indeed;

there comes not a soul to beat her

from the parishes nowadays. —

Ho-ho; here comes God the Father!

Saint Peter! you’re in for it now!

[In a deep voice.]

“Have done with these jack-in-office airs, sir;

Mother Åse shall enter free!”

[Laughs loudly, and turns towards his mother.]

Ay, didn’t I know what would happen?

Now they dance to another tune!

[Uneasily.]

Why, what makes your eyes so glassy?

Mother! Have you gone out of your wits — ?

[Goes to the head of the bed.]

You mustn’t lie there and stare so — !

Speak, mother; it’s I, your boy!

[Feels her forehead and hands cautiously; then throws the string on the chair, and says softly:]

Ay, ay! — You can rest yourself, Grane;

for even now the journey’s done.

[Closes her eyes, and bends over her.]

For all of your days I thank you,

for beatings and lullabies! —

But see, you must thank me back, now —

[Presses his cheek against her mouth]

There; that was the driver’s fare.

THE COTTAR’S WIFE

[entering]

What? Peer! Ah, then we are over

the worst of the sorrow and need!

Dear Lord, but she’s sleeping soundly —

or can she be — ?

PEER

Hush; she is dead.

[KARI weeps beside the body; PEER GYNT walks up and down the room for some time; at last he stops beside the bed.]

PEER

See mother buried with honour.

I must try to fare forth from here.

KARI

Are you faring afar?

PEER

To seaward.

KARI

So far!

PEER

Ay, and further still.

[He goes.]

* * * * *

[On the south-west coast of Morocco. A palm-grove. Under an awning, on ground covered with matting, a

table spread for dinner. Further back in the grove hammocks are

slung. In the offing lies a steam-yacht, flying the Norwegian and

American colours. A jolly-boat drawn up on the beach. It is towards

sunset.]

[PEER GYNT, a handsome middle-aged gentleman, in an elegant travelling-dress, with a gold-rimmed double eyeglass hanging at his waistcoat, is doing the honours at

the head of the table. MR. COTTON, MONSIEUR BALLON, HERR VON

EBERKOPF, and HERR TRUMPETERSTRALE, are seated at the table

finishing dinner.]

PEER GYNT

Drink, gentlemen! If man is made

for pleasure, let him take his fill then.

You know ‘tis written: Lost is lost,

and gone is gone — . What may I hand you?

TRUMPETERSTRALE

As host you’re princely, Brother Gynt!

PEER

I share the honour with my cash,

with cook and steward —

MR. COTTON

Very well;

let’s pledge a toast to all the four!

MONSIEUR BALLON

Monsieur, you have a gout, a ton

that nowadays is seldom met with

among men living en garcon, —

a certain — what’s the word — ?

VON EBERKOPF

A dash,

a tinge of free soul-contemplation,

and cosmopolitanisation,

an outlook through the cloudy rifts

by narrow prejudice unhemmed,

a stamp of high illumination,

an Ur-Natur, with lore of life,

to crown the trilogy, united.

Nicht wahr, Monsieur, ‘twas that you meant?

MONSIEUR BALLON

Yes, very possibly; not quite

so loftily it sounds in French.

VON EBERKOPF

Ei was! That language is so stiff. —

But the phenomenon’s final cause

if we would seek —

PEER

It’s found already.

The reason is that I’m unmarried.

Yes, gentlemen, completely clear

the matter is. What should a man be?

Himself, is my concise reply.

He should regard himself and his.

But can he, as a sumpter-mule

for others’ woe and others’ weal?

VON EBERKOPF

But this same in-and-for-yourself-ness,

I’ll answer for’t, has cost you strife —

PEER

Ay yes, indeed; in former days;

but always I came off with honour.

Yet one time I ran very near

to being trapped against my will.

I was a brisk and handsome lad,

and she to whom my heart was given,

she was of royal family —

MONSIEUR BALLON

Of royal — ?

PEER

[carelessly]

One of those old stocks,

you know the kind —

TRUMPETERSTRALE

[thumping the table]

Those noble-trolls!

PEER

[shrugging his shoulders]

Old fossil Highnesses who make it

their pride to keep plebeian blots

excluded from their line’s escutcheon.

MR. COTTON

Then nothing came of the affair?

MONSIEUR BALLON

The family opposed the marriage?

PEER

Far from it!

MONSIEUR BALLON

Ah!

PEER

[with forbearance]

You understand

that certain circumstances made for

their marrying us without delay.

But, truth to tell, the whole affair

was, first to last, distasteful to me.

I’m finical in certain ways,

and like to stand on my own feet.

And when my father-in-law came out

with delicately veiled demands

that I should change my name and station,

and undergo ennoblement,

with much else that was most distasteful,

not to say quite inacceptable, —

why then I gracefully withdrew,

point-blank declined his ultimatum —

and so renounced my youthful bride.

[Drums on the table with a devout air.]

Yes, yes; there is a ruling Fate!

On that we mortals may rely;

and ‘tis a comfortable knowledge.

MONSIEUR BALLON

And so the matter ended, eh?

PEER

Oh no, far otherwise I found it;

for busy-bodies mixed themselves,

with furious outcries, in the business.

The juniors of the clan were worst;

with seven of them I fought a duel.

That time I never shall forget,

though I came through it all in safety.

It cost me blood; but that same blood

attests the value of my person,

and points encouragingly towards

the wise control of Fate aforesaid.

VON EBERKOPF

Your outlook on the course of life

exalts you to the rank of thinker.

Whilst the mere commonplace empiric

sees separately the scattered scenes,

and to the last goes groping on,

you in one glance can focus all things.

One norm to all things you apply.

You point each random rule of life,

till one and all diverge like rays

from one full-orbed philosophy. —

And you have never been to college?

PEER

I am, as I’ve already said,

exclusively a self-taught man.

Methodically naught I’ve learned;

but I have thought and speculated,

and done much desultory reading.

I started somewhat late in life,

and then, you know, it’s rather hard

to plough ahead through page on page,

and take in all of everything.

I’ve done my history piecemeal;

I never have had time for more.

And, as one needs in days of trial

some certainty to place one’s trust in,

I took religion intermittently.

That way it goes more smoothly down.

One should not read to swallow all,

but rather see what one has use for.

MR. COTTON

Ay, that is practical!

PEER

[lights a cigar]

Dear friends,

just think of my career in general.

In what case came I to the West?

A poor young fellow, empty-handed.

I had to battle sore for bread;

trust me, I often found it hard.

But life, my friends, ah, life is dear,

and, as the phrase goes, death is bitter.

Well! Luck, you see, was kind to me;

old Fate, too, was accommodating.

I prospered; and, by versatility,

I prospered better still and better.

In ten years’ time I bore the name

of Croesus ‘mongst the Charleston shippers.

My fame flew wide from port to port,

and fortune sailed on board my vessels —

MR. COTTON

What did you trade in?

PEER

I did most in Negro slaves for Carolina,

and idol-images for China.

MONSIEUR BALLON

Fi donc!

TRUMPETERSTRALE

The devil, Uncle Gynt!

PEER

You think, no doubt, the business hovered

on the outer verge of the allowable?

Myself I felt the same thing keenly.

It struck me even as odious.

But, trust me, when you’ve once begun,

it’s hard to break away again.

At any rate it’s no light thing,

in such a vast trade-enterprise,

that keeps whole thousands in employ,

to break off wholly, once for all.

That “once for all” I can’t abide,

but own, upon the other side,

that I have always felt respect

for what are known as consequences;

and that to overstep the bounds

has ever somewhat daunted me.

Besides, I had begun to age,

was getting on towards the fifties; —

my hair was slowly growing grizzled;

and, though my health was excellent,

yet painfully the thought beset me:

Who knows how soon the hour may strike,

the jury-verdict be delivered

that parts the sheep and goats asunder?

What could I do? To stop the trade

with China was impossible.

A plan I hit on — opened straightway

a new trade with the self-same land.

I shipped off idols every spring,

each autumn sent forth missionaries,

supplying them with all they needed,

as stockings, Bibles, rum, and rice —

MR. COTTON

Yes, at a profit?

PEER

Why, of course.

It prospered. Dauntlessly they toiled.

For every idol that was sold

they got a coolie well baptised,

so that the effect was neutralised.

The mission-field lay never fallow,

for still the idol-propaganda

the missionaries held in check.

MR. COTTON

Well, but the African commodities?

PEER

There, too, my ethics won the day.

I saw the traffic was a wrong one

for people of a certain age.

One may drop off before one dreams of it.

And then there were the thousand pitfalls

laid by the philanthropic camp;

besides, of course, the hostile cruisers,

and all the wind-and-weather risks.

All this together won the day.

I thought: Now, Peter, reef your sails;

see to it you amend your faults!

So in the South I bought some land,

and kept the last meat-importation,

which chanced to be a superfine one.

They throve so, grew so fat and sleek,

that ‘twas a joy to me, and them too.

Yes, without boasting, I may say

I acted as a father to them, —

and found my profit in so doing.

I built them schools, too, so that virtue

might uniformly be maintained at

a certain general niveau,

and kept strict watch that never its

thermometer should sink below it.

Now, furthermore, from all this business

I’ve beat a definite retreat; —

I’ve sold the whole plantation, and

its tale of live-stock, hide and hair.

At parting, too, I served around,

to big and little, gratis grog,

so men and women all got drunk,

and widows got their snuff as well.

So that is why I trust, — provided

the saying is not idle breath:

Whoso does not do ill, does good, —

my former errors are forgotten,

and I, much more than most, can hold

my misdeeds balanced by my virtues.

VON EBERKOPF

[clinking glasses with him]

How strengthening it is to hear

a principle thus acted out,

freed from the night of theory,

unshaken by the outward ferment!

PEER

[who has been drinking freely during the preceding passages]

We Northland men know how to carry

our battle through! The key to the art

of life’s affairs is simply this:

to keep one’s ear close shut against

the ingress of one dangerous viper.

MR. COTTON

What sort of viper, pray, dear friend?

PEER

A little one that slyly wiles you

to tempt the irretrievable.

[Drinking again.]

The essence of the art of daring,

the art of bravery in act,

is this: To stand with choice-free foot

amid the treacherous snares of life, —

to know for sure that other days

remain beyond the day of battle, —

to know that ever in the rear

a bridge for your retreat stands open.

This theory has borne me on,

has given my whole career its colour;

and this same theory I inherit,

a race-gift, from my childhood’s home.

MONSIEUR BALLON

You are Norwegian?

PEER

Yes, by birth;

but cosmopolitan in spirit.

For fortune such as I’ve enjoyed

I have to thank America.

My amply-furnished library

I owe to Germany’s later schools.

From France, again, I get my waistcoats,

my manners, and my spice of wit, —

from England an industrious hand,

and keen sense for my own advantage.

The Jew has taught me how to wait.

Some taste for dolce far niente

I have received from Italy, —

and one time, in a perilous pass,

to eke the measure of my days,

I had recourse to Swedish steel.

TRUMPETERSTRALE

[lifting up his glass]

Ay, Swedish steel — ?

VON EBERKOPF

The weapon’s wielder demands our homage first of all!

[They clink glasses and drink with him. The wine begins to go to his head.]

MR. COTTON

All this is very good indeed; —

but, sir, I’m curious to know

what with your gold. you think of doing.

PEER

[smiling]

Hm; doing? Eh?

ALL FOUR

[coming closer]

Yes, let us hear!

PEER

Well, first of all, I want to travel.

You see, that’s why I shipped you four,

to keep me company, at Gibraltar.

I needed such a dancing-choir

of friends around my gold-calf-altar —

VON EBERKOPF

Most witty!

MR. COTTON

Well, but no one hoists

his sails for nothing but the sailing.

Beyond all doubt, you have a goal;

and that is — ?

PEER

To be Emperor.

ALL FOUR

What?

PEER

[nodding]

Emperor!

THE FOUR

Where?

PEER

O’er all the world.

MONSIEUR BALLON

But how, friend — ?

PEER

By the might of gold!

That plan is not at all a new one;

it’s been the soul of my career.

Even as a boy, I swept in dreams

far o’er the ocean on a cloud.

I soared with train and golden scabbard, —

and flopped down on all-fours again.

But still my goal, my friends, stood fast. —

There is a text, or else a saying,

somewhere, I don’t remember where,

that if you gained the whole wide world,

but lost yourself, your gain were but

a garland on a cloven skull.

That is the text — or something like it;

and that remark is sober truth.

VON EBERKOPF

But what then is the Gyntish Self?

PEER

The world behind my forehead’s arch,

in force of which I’m no one else

than I, no more than God’s the Devil.