Complete Works of Henrik Ibsen (123 page)

Read Complete Works of Henrik Ibsen Online

Authors: Henrik Ibsen

THE BUTTON-MOULDER

Good morning, Peer Gynt! Where’s the list of your sins?

PEER

Do you think that I haven’t been whistling and shouting as hard as I could?

THE BUTTON-MOULDER

And met no one at all?

PEER

Not a soul but a tramping photographer.

THE BUTTON-MOULDER

Well, the respite is over.

PEER

Ay, everything’s over.

The owl smells the daylight. just list to the hooting!

THE BUTTON-MOULDER

It’s the matin-bell ringing —

PEER

[pointing]

What’s that shining yonder?

THE BUTTON-MOULDER

Only light from a hut.

PEER

And that wailing sound — ?

THE BUTTON-MOULDER

But a woman singing.

PEER

Ay, there — there I’ll find

the list of my sins —

THE BUTTON-MOULDER

[seizing him]

Set your house in order!

[They have come out of the underwood, and are standing near the hut. Day is dawning.]

PEER

Set my house in order? It’s there! Away!

Get you gone! Though your ladle were huge as a coffin,

it were too small, I tell you, for me and my sins!

THE BUTTON-MOULDER

Well, to the third cross-road, Peer; but then — !

[Turns aside and goes.]

PEER

[approaches the hut]

Forward and back, and it’s just as far.

Out and in, and it’s just as strait.

[Stops.]

No! — like a wild, an unending lament,

is the thought: to come back, to go in, to go home.

[Takes a few steps on, but stops again.]

Roundabout, said the Boyg!

[Hears singing in the hut.]

Ah, no; this time at least

right through, though the path may be never so strait!

[He runs towards the hut; at the same moment

SOLVEIG appears in the doorway, dressed for church, with psalm-book

wrapped in a kerchief, and a staff in her hand. She stands there

erect and mild.]

PEER

[flings himself down on the threshold]

Hast thou doom for a sinner, then speak it forth!

SOLVEIG

He is here! He is here! Oh, to God be the praise!

[Stretches out her arms as though groping for him.]

PEER

Cry out all my sins and my trespasses!

SOLVEIG

In nought hast thou sinned, oh my own only

boy.

[Gropes for him again, and finds him.]

THE BUTTON-MOULDER

[behind the house]

The sin-list, Peer Gynt?

PEER

Cry aloud my crime!

SOLVEIG

[sitsdown beside him]

Thou hast made all my life as a beautiful song.

Blessed be thou that at last thou hast come!

Blessed, thrice blessed our Whitsun-morn meeting!

PEER

Then I am lost!

SOLVEIG

There is one that rules all things.

PEER

[laughs]

Lost! Unless thou canst answer riddles.

SOLVEIG

Tell me them.

PEER

Tell them! Come on! To be sure!

Canst thou tell where Peer Gynt has been since we parted?

SOLVEIG

Been?

PEER

With his destiny’s seal on his brow;

been, as in God’s thought he first sprang forth!

Canst thou tell me? If not, I must get me home, —

go down to the mist-shrouded regions.

SOLVEIG

[smiling]

Oh, that riddle is easy.

PEER

Then tell what thou knowest!

Where was I, as myself, as the whole man, the true man?

where was I, with God’s sigil upon my brow?

SOLVEIG

In my faith, in my hope, and in my love.

PEER

[starts back]

What sayest thou — ? Peace! These are juggling words.

Thou art mother thyself to the man that’s there.

SOLVEIG

Ay, that I am; but who is his father?

Surely he that forgives at the mother’s prayer.

PEER

[a light shines in his face; he cries:]

My mother; my wife; oh, thou innocent woman! —

in thy love — oh, there hide me, hide me!

[Clings to her and hides his face in her lap. A long silence. The sun rises.]

SOLVEIG

[sings softly]

Sleep thou, dearest boy of mine!

I will cradle thee, I will watch thee —

The boy has been sitting on his mother’s lap.

They two have been playing all the life-day long.

The boy has been resting at his mother’s breast

all the life-day long. God’s blessing on my joy!

The boy has been lying close in to my heart

all the life-day long. He is weary now.

Sleep thou, dearest boy of mine!

I will cradle thee, I will watch thee.

THE BUTTON-MOULDER’S VOICE

[behind the house]

We’ll meet at the last cross-road again, Peer;

and then we’ll see whether — ; I say no more.

SOLVEIG

[sings louder in the full daylight]

I will cradle thee, I will watch thee;

Sleep and dream thou, dear my boy!

THE END

Translated by William Archer

Completed in early May 1869,

The League of Youth

was Ibsen’s first play in colloquial prose, designating a turning point in his style towards realism and away from verse. In the spring of 1868 Ibsen left Rome and settled in Berchtesgaden in the Bavarian Alps, and it was here that he laid the plans for

The League of Youth

. He started actually writing the play in Dresden, where the family moved to at the beginning of October the same year.

The first draft was begun on October 21st. At this point the title was “The League of Youth or Our Lord & Co.”, but Frederik Hegel, his publisher, persuaded him to drop the sub-title, fearing allegations of blasphemy. Ibsen wrote three drafts of the play before he was satisfied. The final draft was finished on February 28, 1869, after which he spent nine weeks writing the fair copy.

Widely considered as one of Ibsen’s most popular plays in nineteenth-century Norway, the drama is rooted in controversial events of the time, exhibiting witty dialogue and cynical humour. It introduces the character Stensgaard, who poses as a political idealist and gathers a new party around him, the ‘League of Youth’, aiming to eliminate corruption among the old guard and bring his new young group to power. In scheming to be elected, he immerses himself in social and sexual intrigue, culminating in so much confusion that at the end of the play all the women he has planned to marry reject him, his plans for election fail and he is run out of town.

The initial performance received loud applause and glowing reviews by critics in the newspapers. However, by the second performance, Conservatives felt it was an attack on their party and Liberals also believed it was an attack on their party. When both sides showed up for the second performance, a loud ruckus forced the manager to plead for calm and there were continual interruptions. When the play finished, the gas lights were turned off to force the disgruntled mob out of the theatre, with violence continuing into the streets.

It was thought at the time that Ibsen may have modelled his character Stensgaard on the rival dramatist and Liberal party leader Bjornstjerne Bjornson, though Ibsen denied any connection and wrote a letter of apology to Bjornson; still, it would be eleven years before their former friendship would be resumed.

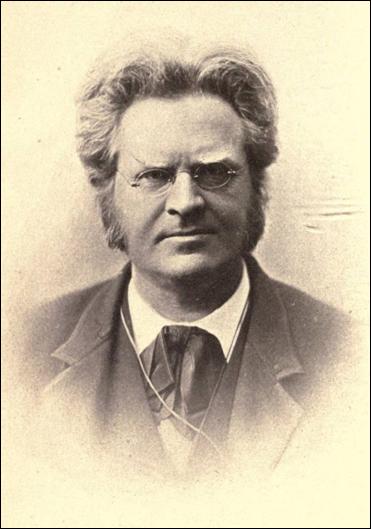

Bjornstjerne Bjornson (1832–1910) was a Norwegian writer and the 1903 Nobel Prize in Literature winner. Bjornson’s friendship with Ibsen was sorely tested when reports claimed that the foolish figure of Stensgaard was based on the former.

CHAMBERLAIN BRATSBERG, owner of the iron-works.

ERIK BRATSBERG, his son, a merchant.

THORA, his daughter.

SELMA, Erik’s wife.

DOCTOR FIELDBO, physician at the Chamberlain’s works.

STENSGÅRD, a lawyer.

MONS MONSEN, of Stonelee.

BASTIAN MONSEN, his son.

RAGNA, his daughter.

HELLE, student of theology, tutor at Stonelee.

RINGDAL, manager of the iron-works.

ANDERS LUNDESTAD, landowner.

DANIEL HEIRE.

MADAM RUNDHOLMEN, widow of a storekeeper and publican.

ASLAKSEN, a printer

A MAID-SERVANT AT THE CHAMBERLAIN’S.

A WAITER.

A WAITRESS AT MADAM RUNDHOLMEN’S.

Townspeople, Guests at the Chamberlain’s, etc. etc.

The action takes place in the neighborhood of the iron-works, not far from a market town in Southern Norway.

[The Seventeenth of May. A Popular fete in the Chamberlain’s grounds. Music and dancing in the background. Coloured lights among the trees. In the middle, somewhat towards the back, a rostrum. To the right, the entrance to a large refreshment-tent; before it, a table with benches. In the foreground on the left, another table, decorated with flowers and surrounded with lounging-chairs.]

[A Crowd of People. LUNDESTAD, with a committee-badge at his button-hole, stands on the rostrum. RINGDAL, also with a committee-badge, at the table on the left.]

LUNDESTAD.

. . . Therefore, friends and fellow citizens,I drink to our freedom! As we have inherited it from our fathers, so will we preserve it for ourselves and for our children! Three cheers for the day! Three cheers for the Seventeenth of May!

THE CROWD.

Hurrah! hurrah! hurrah!

RINGDAL

[as LUNDESTAD descends from the rostrum.]

And one cheer more for old Lundestad!

SOME OF THE CROWD

[hissing.]

Ss! Ss!

MANY VOICES

[drowning the others.]

Hurrah for Lundestad! Long live old Lundestad! Hurrah!

[The CROWD gradually disperses. MONSEN, his son BASTIAN, STENSGARD, and ASLAKSEN make their way forward, through the throng.]

MONSEN.

‘Pon my soul, it’s time he was laid on the shelf!

ASLAKSEN.

It was the local situation he was talking about! Ho-ho!

MONSEN.

He has made the same speech year after year as long as I can remember. Come over here.

STENSGARD.

No, no, not that way, Mr. Monsen. We are quite deserting your daughter.

MONSEN.

Oh, Ragna will find us again.

BASTIAN.

She’s all right; young Helle is with her.

STENSGARD.

Helle?

MONSEN.

Yes, Helle. But

[nudging STENSGARD familiarly]

you have me here, you see, and the rest of us. Come on! Here we shall be out of the crowd, and can discuss more fully what —

[Has meanwhile taken a seat beside the table on the left.]

RINGDAL

[approaching.]

Excuse me, Mr. Monsen — that table is reserved —

STENSGARD.

Reserved? For whom?

RINGDAL

For the Chamberlain’s party.

STENSGARD.

Oh, confound the Chamberlain’s party! There’s none of them here.

RINGDAL

No, but we expect them every minute.

STENSGARD.

Then let them sit somewhere else.

[Takes a chair.]

LUNDESTAD

[laying his hand on the chair.]

No, the table is reserved, and there’s an end of it.

MONSEN

[rising.]

Come, Mr. Stensgard; there are just as good seats over there.

[Crosses to the right.]

Waiter! Ha, no waiters either. The Committee should have seen to that in time. Oh, Aslaksen, just go in and get us four bottles of champagne. Order the dearest; tell them to put it down to Monsen!

[ASLAKSEN goes into the tent; the three others seat themselves.]

LUNDESTAD

[goes quietly over to them and addresses STENSGARD.]

I hope you won’t take it ill —

MONSEN.

Take it ill! Good gracious, no! Not in the least.

LUNDESTAD

[Still to STENSGARD.]

It’s not my doing; it’s the Committee that decided —

MONSEN.

Of course. The Committee orders, and we must obey.

LUNDESTAD

[as before.]

You see, we are on the Chamberlain’s own ground here. He has been so kind as to throw open his park and garden for this evening; so we thought —

STENSGARD.

We’re extremely comfortable here, Mr. Lundestad — if only people would leave us in peace — the crowd, I mean.

LUNDESTAD

[unruffled.]

Very well; then it’s all right.

[Goes towards the back.]

ASLAKSEN

[entering from the tent.]

The waiter is just coming with the wine.

[Sits.]

MONSEN.

A table apart, under special care of the Committee! And on our Independence Day of all others! There you have a specimen of the way things go.

STENSGARD.

But why on earth do you put up with all this, you good people?

MONSEN.

The habit of generations, you see.

ASLAKSEN.

You’re new to the district, Mr. Stensgard. If only you knew a little of the local situation —

A WAITER

[brings champagne.]

Was it you that ordered — ?

ASLAKSEN.

Yes, certainly; open the bottle.

THE WAITER

[pouring out the wine.]

It goes to your account, Mr. Monsen?

MONSEN.

The whole thing; don’t be afraid.

[The WAITER goes.]

MONSEN

[clinks glasses with STENSGARD.]

Here’s welcome among us, Mr. Stensgard! It gives me great pleasure to have made your acquaintance; I cannot but call it an honour to the district that such a man should settle here. The newspapers have made us familiar with your name, on all sorts of public occasions. You have great gifts of oratory, Mr. Stensgard, and a warm heart for the public weal. I trust you will enter with life and vigour into the — h’m, into the —

ASLAKSEN.

The local situation.

MONSEN.

Oh yes, the local situation. I drink to that.

[They drink.]

STENSGARD.

Whatever I do, I shall certainly put life and vigour into it.

MONSEN.

Bravo! Hear, hear! Another glass in honour of that promise.

STENSGARD.

No, stop; I’ve already —

MONSEN.

Oh, nonsense! Another glass, I say — to seal the bond! They clink glasses and drink. During what follows BASTIAN keeps on filling the glasses as soon as they are empty.

MONSEN.

However — since we have got upon the subject — I must tell you that it’s not the Chamberlain himself that keeps everything under his thumb. No, sir — old Lundestad is the man that stands behind and drives the sledge.

STENSGARD.

So I am told in many quarters. I can’t understand how a Liberal like him —

MONSEN.

Lundestad? Do you call Anders Lundestad a Liberal? To be sure, he professed Liberalism in his young days, when he was still at the foot of the ladder. And then he inherited his seat in Parliament from his father. Good Lord! everything runs in families here.

STENSGARD.

But there must be some means of putting a stop to all these abuses.

ASLAKSEN.

Yes, damn it all, Mr. Stensgard — see if you can’t put a stop to them!

STENSGARD.

I don’t say that I —

ASLAKSEN.

Yes, you! You are just the man. You have the gift of gab, as the saying goes; and what’s more: you have the pen of a ready writer. My paper’s at your disposal, you know.

MONSEN.

If anything is to be done, it must be done quickly. The preliminary election comes on in three days now.

STENSGARD.

And if you were elected, your private affairs would not prevent your accepting the charge?

MONSEN.

My private affairs would suffer, of course; but if it appeared that the good of the community demanded the sacrifice, I should have to put aside all personal considerations.

STENSGARD.

Good; that’s good. And you have a party already: that I can see clearly.

MONSEN.

I flatter myself the majority of the younger, go-ahead generation —

ASLAKSEN.

H’m, h’m! ‘ware spies!

[DANIEL HEIRE enters from the tent; he peers about shortsightedly, and approaches.]

HEIRE.

May I beg for the loan of a spare seat; I want to sit over there.

MONSEN.

The benches are fastened here, you see; but won’t you take a place at this table?

HEIRE.

Here? At this table? Oh, yes, with pleasure.

[Sits.]

Dear, dear! Champagne, I believe.

MONSEN.

Yes; won’t you join us in a glass?

HEIRE.

No, thank you! Madam Rundholmen’s champagne — Well, well, just half a glass to keep you company. If only one had a glass, now.

MONSEN.

Bastian, go and get one.

BASTIAN.

Oh, Aslaksen, just go and fetch a glass.

[ASLAKSEN goes into the tent. A pause.]

HEIRE.

Don’t let me interrupt you, gentlemen. I wouldn’t for the world — ! Thanks, Aslaksen.

[Bows to STENSGARD.]

A strange face — a recent arrival! Have I the pleasure of addressing our new legal luminary, Mr. Stensgard?

MONSEN.

Quite right.

[Introducing them.]

Mr. Stensgard, Mr. Daniel Heire —

BASTIAN.

Capitalist.

HEIRE.

Ex-capitalist, you should rather say. It’s all gone now; slipped through my fingers, so to speak. Not that I’m bankrupt — for goodness’ sake don’t think that.

MONSEN.

Drink, drink, while the froth is on it.

HEIRE.

But rascality, you understand — sharp practice and so forth — I say no more. Well, well, I am confident it is only temporary. When I get my outstanding law-suits and some other little matters off my hands, I shall soon be on the track of our aristocratic old Reynard the Fox. Let us drink to that — You won’t, eh?

STENSGARD.

I should like to know first who your aristocratic old Reynard the Fox may be.

HEIRE.

Hee-hee; you needn’t look so uncomfortable, man. You don’t suppose I’m alluding to Mr. Monsen. No one can accuse Mr. Monsen of being aristocratic. No; it’s Chamberlain Bratsberg, my dear young friend.

STENSGARD.

What! In money matters the Chamberlain is surely above reproach.

HEIRE.

You think so, young man? H’m; I say no more.

[Draws nearer.]

Twenty years ago I was worth no end of money. My father left me a great fortune. You’ve heard of my father, I daresay? No? Old Hans Heire? They called him Gold Hans. He was a shipowner: made heaps of money in the blockade time; had his window-frames and door-posts gilded; he could afford it — I say no more; so they called him Gold Hans.

ASLAKSEN.

Didn’t he gild his chimney-pots too?

HEIRE.

No; that was only a penny-a-liner’s lie; invented long before your time, however. But he made the money fly; and so did I in my time. My visit to London, for instance — haven’t you heard of my visit to London? I took a prince’s retinue with me. Have you really not heard of it, eh? And the sums I have lavished on art and science! And on bringing rising talent to the front!

ASLAKSEN

[rises.]

Well, good-bye, gentlemen.

MONSEN.

What? Are you leaving us?

ASLAKSEN.

Yes; I want to stretch my legs a bit.

[Goes.]

HEIRE

[speaking low.]

He was one of them — just as grateful as the rest, hee-hee! Do you know, I kept him a whole year at college?

STENSGARD.

Indeed? Has Aslaksen been to college?

HEIRE.

Like young Monsen. He made nothing of it; also like — I say no more. Had to give him up, you see; he had already developed his unhappy taste for spirits —

MONSEN.

But you’ve forgotten what you were going to tell Mr. Stensgard about the Chamberlain.

HEIRE.

Oh, it’s a complicated business. When my father was in his glory, things were going downhill with the old Chamberlain — this one’s father, you understand; he was a Chamberlain too.

BASTIAN.

Of course; everything runs in families here.

HEIRE.

Including the social graces — I say no more. The conversion of the currency, rash speculations, extravagances he launched out into, in the year 1816 or thereabouts, forced him to sell some of his land.

STENSGARD.

And your father bought it?

HEIRE.

Bought and paid for it. Well, what then? I come into my property; I make improvements by the thousand —