Complete Works of Henrik Ibsen (15 page)

Read Complete Works of Henrik Ibsen Online

Authors: Henrik Ibsen

Translated by Charles Archer

In 1851, Ibsen moved to Bergen to work at the Det norske Theater to assist as a ‘dramatic author’. In the course of his six years in Bergen, he wrote and had staged six of his plays. He also worked as a stage director and in this manner acquired insight into all facets of the theatre profession. In Bergen he met Suzannah Daae Thoresen, whom he later married and with whom he fathered his only son Sigurd.

Lady Inger of Oestraat

was written during Ibsen’s period as director at the Det norske Theater. In October 1854 he handed the completed script to Peter Blytt, claiming it was a manuscript of a historical drama sent to him by a friend in Christiania, who wished to remain anonymous and would like it to be performed on the Bergen stage, if it was considered worthy of acceptance. Having released two flops, Ibsen’s self-esteem was at a low level, explaining his concealment of his authorship. Blytt was enthusiastic about the script and the board of Det norske Theater agreed that the play was suitable for the projected gala performance on January 2, 1855 on the occasion of the theatre’s fifth anniversary.

In working on this play, Ibsen used several historical sources, with particular interest in the Danish-Norwegian union. Two publications by Danish historians are thought to have played a special role in Ibsen’s play: Caspar Paludan-Müller’s work Gr

evens feide: skildret efter trykte og utrykte Kilder

(“The Count’s Feud, from printed and unprinted sources”), published in two volumes in 1853/54, and volume one of

Samlinger til det Norske Folks Sprog og Historie

(“Collections on the Language and History of the Norwegian People”), published in 1833. The former contains a description of Ingerd Ottisdatter’s attempt to start a Norwegian rising in the cause of independence in 1527-28. The latter contains a collection of letters from 1525-29, collected and edited by Professor Gr. F. Lundh. However, Ibsen’s treatment of the historical material is very free, with some critics arguing that it is not in the least an historical work.

Just before the first night, Ibsen involuntarily revealed himself to be the author of the play. An anecdote records that there was an incident during rehearsals when he rushed out of the wings, interrupted Jacob Prom, the actor playing Niels Lykke, in one of his longer speeches, and delivered it himself in the way he thought it should be delivered. This took place without Ibsen looking at the prompter’s script and in such a way that those present could have no doubt that he was the author.

Lady Inger of Oestraat

was performed as planned at Det norske Theater on January 2, 1855, but this production was not a success and the public showed less interest than expected, resulting in the play being performed only twice.

The play was inspired by the life of Inger, Lady of Austraat and reflects the birth of Romantic Nationalism in the Norway of that period, which had a strongly anti-Danish sentiment. The drama concerns the Scandinavia of 1510–1540 as the Kalmar Union collapsed, when the impact of the Reformation was becoming evident in Norway and a last desperate struggle was being mounted to maintain Norwegian independence. Its initial sentiments were so strongly anti-Danish that Ibsen ultimately had to tone them down.

The Det norske Theater in Bergen is regarded as the first pure Norwegian stage theatre. It opened in 1850 and closed in 1863, due to bankruptcy.

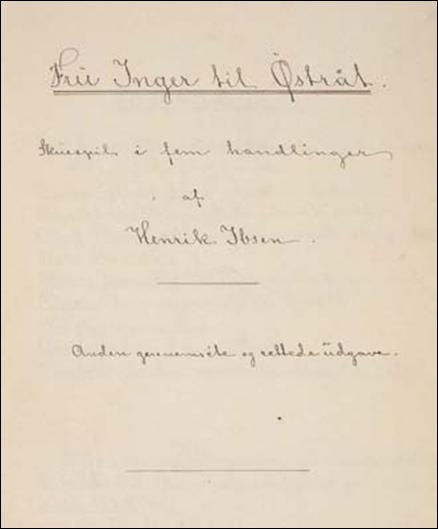

The title page of the manuscript

Agnes Mowinckel playing the part of Lady Inger in 1921

LADY INGER OTTISDAUGHTER ROMER, widow of High Steward Nils Gyldenlove.

ELINA GYLDENLOVE, her daughter.

NILS LYKKE, Danish knight and councilor.

OLAF SKAKTAVL, an outlawed Norwegian noble.

NILS STENSSON.

JENS BIELKE, Swedish commander.

BIORN, major-domo at Ostrat.

FINN, a servant.

EINAR HUK, bailiff at Ostrat.

Servants, peasants, and Swedish men-at-arms.

The action takes place at Ostrat Manor, on the Trondhiem Fiord,

the year 1528.

[PRONUNCIATION of NAMES. — Ostrat=Ostrot; Inger=Ingher (g nearly as

in “ringer”); Gyldenlove=Ghyldenlove; Elina (Norwegian, Eline)=

Eleena; Stennson=Staynson; Biorn=Byorn; Jens Bielke=Yens Byelke;

Huk=Hook. The final e’s and the o’s pronounced much as in German.]

Producer’s Notes:

1. Diacritical Marks in Characters’ names:

Romer, umlaut (diaresis) above the “o”

Ostrat, umlaut above the “O”, ring above the “a”

Gyldenlove, umlaut above the “o”

Biorn, umlaut above the “o”

2. All the text inside parentheses in the original is printed in italics, save for the characters’ names. I’ve eliminated the usual markings indicating

italics

for the sake of readability. — D. L.

(A room at Ostrat. Through an open door in the back, the Banquet Hall is seen in faint moonlight, which shines fitfully through a deep bow-window in the opposite wall. To the right, an entrance- door; further forward, a curtained window. On the left, a door leading to the inner rooms; further forward a large, open fireplace, which casts a glow over the room. It is a stormy evening.)

(BIORN and FINN are sitting by the fireplace. The latter is occupied in polishing a helmet. Several pieces of armour lie near them, along with a sword and shield.)

FINN (after a pause). Who was Knut* Alfson?

* Pronounce

Knoot

.

BIORN. My Lady says he was the last of Norway’s knighthood.

FINN. And the Danes killed him at Oslo-fiord?

BIORN. Ask any child of five, if you know not that.

FINN. So Knut Alfson was the last of our knighthood? And now he’s dead and gone! (Holds up the helmet.) Well then, hang thou scoured and bright in the Banquet Hall; for what art thou now but an empty nut-shell? The kernel — the worms have eaten that many a winter agone. What say you, Biorn — may not one call Norway’s land an empty nut- shell, even like the helmet here; bright without, worm-eaten within?

BIORN. Hold your peace, and mind your work! — Is the helmet ready?

FINN. It shines like silver in the moonlight.

BIORN. Then put it by. ——

—— See here; scrape the rust off

the sword.

FINN (turning the sword over and examining it). Is it worth

while?

BIORN. What mean you?

FINN. The edge is gone.

BIORN. What’s that to you? Give it me. ——

—— Here, take the shield.

FINN (as before). There’s no grip to it!

BIORN (mutters). If once I got a grip on

you

——

(FINN hums to himself for a while.)

BIORN. What now?

FINN. An empty helmet, an edgeless sword, a shield without a grip — there’s the whole glory for you. I see not that any can blame Lady Inger for leaving such weapons to hang scoured and polished on the walls, instead of rusting them in Danish blood.

BIORN. Folly! Is there not peace in the land?

FINN. Peace? Ay, when the peasant has shot away his last arrow, and the wolf has reft the last lamb from the fold, then is there peace between them. But ‘tis a strange friendship. Well well; let that pass. It is fitting, as I said, that the harness hang bright in the hall; for you know the old saw: “Call none a man but the knightly man.” Now there is no knight left in our land; and where no man is, there must women order things; therefore ——

BIORN. Therefore — therefore I order you to hold your foul prate!

(Rises.)

It grows late. Go hang helm and harness in the hall again.

FINN (in a low voice). Nay, best let it be till tomorrow.

BIORN. What, do you fear the dark?

FINN. Not by day. And if so be I fear it at even, I am not the only one. Ah, you look; I tell you in the housefolk’s room there is talk of many things. (Lower.) They say that night by night a tall figure, clad in black, walks the Banquet Hall.

BIORN. Old wives’ tales!

FINN. Ah, but they all swear ‘tis true.

BIORN. That I well believe.

FINN. The strangest of all is that Lady Inger thinks the same ——

BIORN (starting). Lady Inger? What does she think?

FINN. What Lady Inger thinks no one can tell. But sure it is that she has no rest in her. See you not how day by day she grows thinner and paler? (Looks keenly at him.) They say she never sleeps — and that it is because of the dark figure ——

(While he is speaking, ELINA GYLDENLOVE has appeared in the half-open door on the left. She stops and listens, unobserved.)

BIORN. And you believe such follies?

FINN. Well, half and half. There be folk, too, that read things another way. But that is pure malice, for sure. — Hearken, Biorn — know you the song that is going round the country?

BIORN. A song?

FINN. Ay, ‘tis on all folks’ lips. ‘Tis a shameful scurril thing, for sure; yet it goes prettily. Just listen (sings in a low voice):

Dame Inger sitteth in Ostrat fair,

She wraps her in costly furs —

She decks her in velvet and ermine and vair,

Red gold are the beads that she twines in her hair —

But small peace in that soul of hers.

Dame Inger hath sold her to Denmark’s lord.

She bringeth her folk ‘neath the stranger’s yoke —

In guerdon whereof ——

——

(BIORN enraged, seizes him by the throat. ELINA GYLDENLOVE

withdraws without having been seen.)

BIORN. And I will send you guerdonless to the foul fiend, if

you prate of Lady Inger but one unseemly word more.

FINN (breaking from his grasp). Why — did

I

make the song?

(The blast of a horn is heard from the right.)

BIORN. Hush — what is that?

FINN. A horn. So we are to have guests to-night.

BIORN (at the window). They are opening the gate. I hear the clatter of hoofs in the courtyard. It must be a knight.

FINN. A knight? A knight can it scarce be.

BIORN. Why not?

FINN. You said it yourself: the last of our knighthood is dead and gone. (Goes out to the right.)

BIORN. The accursed knave, with his prying and peering! What avails all my striving to hide and hush things? They whisper of her even now —— ; ere long will all men be clamouring for ——

ELINA (comes in again through the door on the left; looks round her, and says with suppressed emotion). Are you alone, Biorn?

BIORN. Is it you, Mistress Elina?

ELINA. Come, Biorn, tell me one of your stories; I know you have more to tell than those that ——

BIORN. A story? Now — so late in the evening —— ?

ELINA. If you count from the time when it grew dark at Ostrat,

it is late indeed.

BIORN. What ails you? Has aught crossed you? You seem so

restless.

ELINA. May be so.

BIORN. There is something the matter. I have hardly known you

this half year past.

ELINA. Bethink you: this half year past my dearest sister Lucia

has been sleeping in the vault below.

BIORN. That is not all, Mistress Elina — it is not that alone that makes you now thoughtful and white and silent, now restless and ill at ease, as you are to-night.

ELINA. You think so? And wherefore not? Was she not gentle and pure and fair as a summer night? Biorn, I tell you, Lucia was dear to me as my life. Have you forgotten how many a time, as children, we sat on your knee in the winter evenings? You sang songs to us, and told us tales ——

BIORN. Ay, then your were blithe and gay.

ELINA. Ah, then, Biorn! Then I lived a glorious life in the fable-land of my own imaginings. Can it be that the sea-strand was naked then as now? If it were so, I did not know it. It was there I loved to go, weaving all my fair romances; my heroes came from afar and sailed again across the sea; I lived in their midst, and set forth with them when they sailed away. (Sinks on a chair.) Now I feel so faint and weary; I can live no longer in my tales. They are only — tales. (Rises hastily.) Biorn, do you know what has made me sick? A truth; a hateful, hateful truth, that gnaws me day and night.

BIORN. What mean you?

ELINA. Do you remember how sometimes you would give us good counsel and wise saws? Sister Lucia followed them; but I — ah, well-a-day!

BIORN (consoling her). Well, well —— !

ELINA. I know it — I was proud and self-centred! In all our games, I would still be the Queen, because I was the tallest, the fairest, the wisest! I know it!

BIORN. That is true.

ELINA. Once you took me by the hand and looked earnestly at me, and said: “Be not proud of your fairness, or your wisdom; but be proud as the mountain eagle as often as you think: I am Inger Gyldenlove’s daughter!”

BIORN. And was it not matter enough for pride?

ELINA. You told me so often enough, Biorn! Oh, you told me so many tales in those days. (Presses his hand.) Thanks for them all! Now, tell me one more; it might make me light of heart again, as of old.

BIORN. You are a child no longer.

ELINA. Nay, indeed! But let me dream that I am. — Come, tell on!

(Throws herself into a chair. BIORN sits in the chimney-corner.)

BIORN. Once upon a time there was a high-born knight ——

ELINA (who has been listening restlessly in the direction of the hall, seizes his arm and breaks out in a vehement whisper). Hush! No need to shout so loud; I can hear well!

BIORN (more softly). Once upon a time there was a high-born

knight, of whom there went the strange report ——

(ELINA half-rises and listens in anxious suspense in the

direction of the hall.)

BIORN. Mistress Elina, what ails you?

ELINA (sits down again). Me? Nothing. Go on.

BIORN. Well, as I was saying, when he did but look straight in a woman’s eyes, never could she forget it after; her thoughts must follow him wherever he went, and she must waste away with sorrow.

ELINA. I have heard that tale ——

—— And, moreover, ‘tis no tale you are telling, for the knight you speak of is Nils Lykke, who sits even now in the Council of Denmark ——

BIORN. May be so.

ELINA. Well, let it pass — go on!

BIORN. Now it happened once ——

ELINA (rises suddenly). Hush; be still!

BIORN. What now? What is the matter?

ELINA. It

is

there! Yes, by the cross of Christ it

is

there!

BIORN (rises). What is there? Where?

ELINA. It is she — in the hall. (Goes hastily towards the hall.)

BIORN (following). How can you think —— ? Mistress Elina, go to your chamber!

ELINA. Hush; stand still! Do not move; do not let her see you! Wait — the moon is coming out. Can you not see the black-robed figure —— ?

BIORN. By all the holy —— !

ELINA. Do you see — she turns Knut Alfson’s picture to the wall.

Ha-ha; be sure it looks her too straight in the eyes!

BIORN. Mistress Elina, hear me!

ELINA (going back towards the fireplace). Now I know what I know!

BIORN (to himself). Then it is true!

ELINA. Who was it, Biorn? Who was it?

BIORN. You saw as plainly as I.

ELINA. Well? Whom did I see?

BIORN. You saw your mother.

ELINA (half to herself). Night after night I have heard her steps in there. I have heard her whispering and moaning like a soul in pain. And what says the song —— Ah, now I know! Now I know that ——

BIORN. Hush!

(LADY INGER GYLDENLOVE enters rapidly from the hall, without noticing the others; she goes to the window, draws the curtain, and gazes out as if watching for some one on the high road; after a while, she turns and goes slowly back into the hall.)

ELINA (softly, following her with her eyes). White as a corpse —— !

(An uproar of many voices is heard outside the door on the right.)

BIORN. What can this be?