Complete Works of Henrik Ibsen (201 page)

Read Complete Works of Henrik Ibsen Online

Authors: Henrik Ibsen

Helmer

. And can you tell me what I have done to forfeit your love?

Nora

. Yes, indeed I can. It was to-night, when the wonderful thing did not happen; then I saw you were not the man I had thought you.

Helmer

. Explain yourself better — I don’t understand you.

Nora

. I have waited so patiently for eight years; for, goodness knows, I knew very well that wonderful things don’t happen every day. Then this horrible misfortune came upon me; and then I felt quite certain that the wonderful thing was going to happen at last. When Krogstad’s letter was lying out there, never for a moment did I imagine that you would consent to accept this man’s conditions. I was so absolutely certain that you would say to him: Publish the thing to the whole world. And when that was done —

Helmer

. Yes, what then? — when I had exposed my wife to shame and disgrace?

Nora

. When that was done, I was so absolutely certain, you would come forward and take everything upon yourself, and say: I am the guilty one.

Helmer

. Nora — !

Nora

. You mean that I would never have accepted such a sacrifice on your part? No, of course not. But what would my assurances have been worth against yours? That was the wonderful thing which I hoped for and feared; and it was to prevent that, that I wanted to kill myself.

Helmer

. I would gladly work night and day for you, Nora — bear sorrow and want for your sake. But no man would sacrifice his honour for the one he loves.

Nora

. It is a thing hundreds of thousands of women have done.

Helmer

. Oh, you think and talk like a heedless child.

Nora

. Maybe. But you neither think nor talk like the man I could bind myself to. As soon as your fear was over — and it was not fear for what threatened me, but for what might happen to you — when the whole thing was past, as far as you were concerned it was exactly as if nothing at all had happened. Exactly as before, I was your little skylark, your doll, which you would in future treat with doubly gentle care, because it was so brittle and fragile. (

Getting up

.) Torvald — it was then it dawned upon me that for eight years I had been living here with a strange man, and had borne him three children — . Oh! I can’t bear to think of it! I could tear myself into little bits!

Helmer

(

sadly

). I see, I see. An abyss has opened between us — there is no denying it. But, Nora, would it not be possible to fill it up?

Nora

. As I am now, I am no wife for you.

Helmer

. I have it in me to become a different man.

Nora

. Perhaps — if your doll is taken away from you.

Helmer

. But to part! — to part from you! No, no, Nora, I can’t understand that idea.

Nora

(

going out to the right

). That makes it all the more certain that it must be done. (

She comes back with her cloak and hat and a small bag which she puts on a chair by the table

.)

Helmer

. Nora, Nora, not now! Wait till tomorrow.

Nora

(

putting on her cloak

). I cannot spend the night in a strange man’s room.

Helmer

. But can’t we live here like brother and sister — ?

Nora

(

putting on her hat

). You know very well that would not last long. (

Puts the shawl round her

.) Good-bye, Torvald. I won’t see the little ones. I know they are in better hands than mine. As I am now, I can be of no use to them.

Helmer

. But some day, Nora — some day?

Nora

. How can I tell? I have no idea what is going to become of me.

Helmer

. But you are my wife, whatever becomes of you.

Nora

. Listen, Torvald. I have heard that when a wife deserts her husband’s house, as I am doing now, he is legally freed from all obligations towards her. In any case I set you free from all your obligations. You are not to feel yourself bound in the slightest way, any more than I shall. There must be perfect freedom on both sides. See, here is your ring back. Give me mine.

Helmer

. That too?

Nora

. That too.

Helmer

. Here it is.

Nora

. That’s right. Now it is all over. I have put the keys here. The maids know all about everything in the house — better than I do. Tomorrow, after I have left her, Christine will come here and pack up my own things that I brought with me from home. I will have them sent after me.

Helmer

. All over! All over! — Nora, shall you never think of me again?

Nora

. I know I shall often think of you and the children and this house.

Helmer

. May I write to you, Nora?

Nora

. No — never. You must not do that.

Helmer

. But at least let me send you —

Nora

. Nothing — nothing —

Helmer

. Let me help you if you are in want.

Nora

. No. I can receive nothing from a stranger.

Helmer

. Nora — can I never be anything more than a stranger to you?

Nora

(

taking her bag

). Ah, Torvald, the most wonderful thing of all would have to happen.

Helmer

. Tell me what that would be!

Nora

. Both you and I would have to be so changed that — . Oh, Torvald, I don’t believe any longer in wonderful things happening.

Helmer

. But I will believe in it. Tell me? So changed that — ?

Nora

. That our life together would be a real wedlock. Good-bye. (

She goes out through the hall

.)

Helmer

(

sinks down on a chair at the door and buries his face in his hands

). Nora! Nora! (

Looks round, and rises

.) Empty. She is gone. (

A hope flashes across his mind

.) The most wonderful thing of all — ?

(

The sound of a door shutting is heard from below

.)

TS

Translated by William Archer

First staged in 1882,

Ghosts

was written in 1881 and once more presents a scathing commentary on 19th-century morality.

Originally written in Danish, with the title “Gengangere” that literally translates as “again walkers”, the title can also refer to people that frequently appear in the same places. As early as November 1880, whilst still living in Rome, Ibsen was meditating on a new play to follow the sensation caused by

A Doll’s House

. When visiting Sorrento in the summer of 1881, the playwright was hard at work upon this new drama, which was finished by the end of November and published in Copenhagen on 13 December. Its world stage première was on 20 May

The play involves Helen Alving, who is about to dedicate an orphanage she has built in the memory of her dead husband, Captain Alving. She reveals to Pastor Manders, her spiritual advisor, that she has ‘hidden the evils of her marriage’ and has built the orphanage to deplete her husband’s wealth so that their son, Oswald, might not inherit anything from him. Pastor Manders had previously advised her to return to her husband despite his philandering and she had followed his advice in the belief that her love for her husband would eventually reform him. However, her husband’s wicked ways continued until his death and Mrs. Alving was unable to leave him for fear of being shunned by the community. During the action of the play she discovers that her son Oswald, whom she had sent away so that he would not be corrupted by his father, is suffering from inherited syphilis and has fallen in love with Regina Engstrand, Mrs. Alving’s maid. Tragedy further strikes when it is also revealed that Regina is the illegitimate daughter of Captain Alving and therefore Oswald’s own half-sister.

In many ways

Ghosts

forms a sequel of sorts to

A Doll’s House

. Instead of the general query, “Did Nora return to her children?”, Ibsen puts the stress on the problem of what would have happened to Nora’s children had she and Helmer persisted in living the life of lies they were accustomed to. The moral corruption of Oswald Alving, his degenerate relationship with the serving maid, who proves to be in the end his half-sister, are the direct product of the moral unsavoriness of Captain Alving, whose past life has been covered through the moral smugness of his wife, acting under the advice of the conventional minister, Pastor Manders. If Dr. Rank, in

A Doll’s House

, was suffering from the sins of his fathers, Oswald Alving is the product of the moral degeneracy of his father and the moral weakness of his mother. Thus, Ibsen’s

Ghosts

becomes an answer to the question whether Nora had a right to leave her children when she did.

Much like its predecessor,

Ghosts

was deliberately sensational, offending many critics with what was regarded at the time as shocking indecency, due to the handling of themes such as infidelity, venereal disease and, worst of all, incest. One English critic later described the play as “a dirty deed done in public”, whilst another newspaper critic labelled the work as, “Revoltingly suggestive and blasphemous ... Characters either contradictory in themselves, uninteresting or abhorrent”. Meanwhile,

Ghosts

also scandalised the Norwegian society of the day and Ibsen was strongly criticised. In 1898 when the playwright was presented to King Oscar II of Sweden and Norway, at a dinner in Ibsen’s honour, the King told Ibsen that

Ghosts

was not a good play. After a pause, Ibsen exploded, “Your Majesty, I had to write

Ghosts

!”

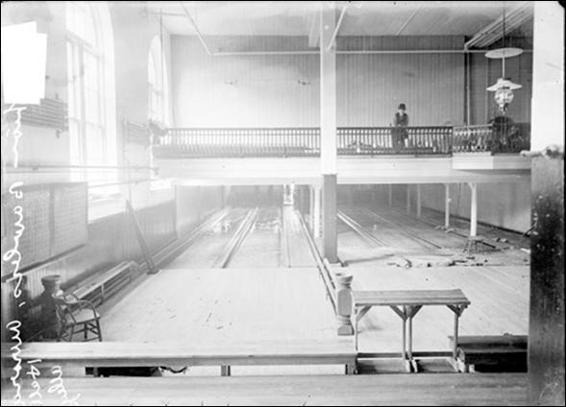

The first edition

‘Ghosts’ was not performed in the theatre until May 1882, when a Danish touring company produced it in the Aurora Turner Hall in Chicago. The hall was later converted into a bowling alley.