Complete Works of Henrik Ibsen (286 page)

Read Complete Works of Henrik Ibsen Online

Authors: Henrik Ibsen

Brack.

[In the arm-chair, calls out gaily.]

Every blessed evening, with all the pleasure in life, Mrs. Tesman! We shall get on capitally together, we two!

Hedda.

[Speaking loud and clear.]

Yes, don’t you flatter yourself we will, Judge Brack? Now that you are the one cock in the basket —

A shot is heard within.

Tesman, mrs

.

Elvsted

, and

Brack

leap to their feet.

Tesman.

Oh, now she is playing with those pistols again.

He throws back the curtains and runs in, followed by

Mrs

.

Elvsted

.

Hedda

lies stretched on the sofa, lifeless. Confusion and cries.

Berta

enters in alarm from the right.

Tesman.

[Shrieks to

Brack

.]

Shot herself! Shot herself in the temple! Fancy that!

Brack.

[Half-fainting in the arm-chair.]

Good God! — people don’t do such things.

ER

Translated by Edmund Gosse and William Archer

In July 1891, Ibsen returned to Christiania after 27 years abroad and

The Master Builder

was written the following year, though he was influenced by his previous experiences with 18-year-old Emilie Bardach. Bardach inspired the character Hilde Wangel, though she is presented as far more calculating and coquettishly in the play than she was most likely to have acted towards Ibsen. A friend of the playwright once wrote of Ibsen’s encounter with Bardach: “Ibsen related how he had met in the Tyrol, where she was staying with her mother, a Viennese girl of very remarkable character, who had at once made him her confidant. The gist of it was that she was not interested in the idea of marrying some decently brought-up young man; most likely she would never marry. What tempted, fascinated and delighted her was to lure other women’s husbands away from them. She was a demonic little wrecker; she often seemed to him like a little bird of prey, who would gladly have included him among her victims. He had studied her very, very closely.”

On August 9, 1892 Ibsen began work on what was to be the final version of the play, published by Gyldendalske Boghandels Forlag in Christiania on December 12th and in Copenhagen on December 14th

The Master Builder

was a reading in Norwegian at the Theatre Royal in the Haymarket in London on December 7th 1892, five days before the play was even published, as part of William Heinemann’s strategy to secure the copyright for himself. The first professional staging of the play was on January 19, 1893 at the Lessing-Theater in Berlin, with the director Emanuel Reicher playing the title role.

The action concerns Halvard Solness, the master builder of the title, who has become the most successful builder in his home town by a fortunate series of coincidences. He had previously conceived these events and wished for them to come to pass, but never actually did anything about them. By the time his wife’s ancestral home was destroyed by a fire in a clothes cupboard, he had already imagined how he could cause such an accident and then profit from it by dividing the land on which the house stood into plots and covering it with homes for sale. Between this fortuitous occurrence and some chance misfortunes of his competitors Solness comes to believe that he has only to wish for something to happen in order for it to come about. He rationalises this as a particular gift from God, bestowed so that, through his unnatural success, he can carry out His ordained work of church building. The plot also concerns the destructive outcome of a middle-aged, professional man’s infatuation with a young and flirtatious woman.

The first edition

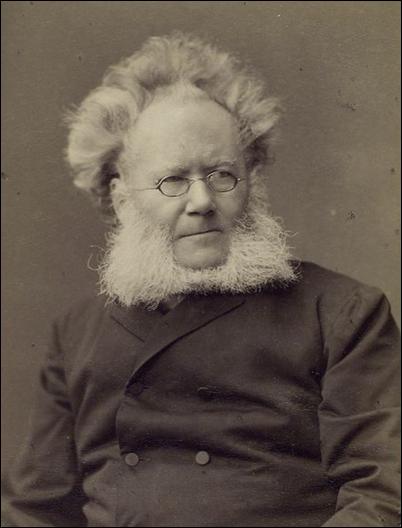

Ibsen, close to the time of writing this play

With

The Master Builder

— or

Master Builder Solness

, as the title runs in the original — we enter upon the final stage in Ibsen’s career. “You are essentially right,” the poet wrote to Count Prozor in March 1900, “when you say that the series which closes with the Epilogue (

When We Dead Awaken

) began with

Master Builder Solness

.”

“Ibsen,” says Dr. Brahm, “wrote in Christiania all the four works which he thus seems to bracket together —

Solness

,

Eyolf

,

Borkman

, and

When We Dead Awaken

. He returned to Norway in July 1891, for a stay of indefinite length; but the restless wanderer over Europe was destined to leave his home no more.... He had not returned, however, to throw himself, as of old, into the battle of the passing day. Polemics are entirely absent from the poetry of his old age. He leaves the State and Society at peace. He who had departed as the creator of Falk

[in

Love’s Comedy

]

now, on his return, gazes into the secret places of human nature and the wonder of his own soul.”

Dr. Brahm, however, seems to be mistaken in thinking that Ibsen returned to Norway with no definite intention of settling down. Dr. Julius Elias (an excellent authority) reports that shortly before Ibsen left Munich in 1891, he remarked one day, “I must get back to the North!” “Is that a sudden impulse?” asked Elias. “Oh no,” was the reply; “I want to be a good head of a household and have my affairs in order. To that end I must consolidate may property, lay it down in good securities, and get it under control — and that one can best do where one has rights of citizenship.” Some critics will no doubt be shocked to find the poet whom they have written down an “anarchist” confessing such bourgeois motives.

After his return to Norway, Ibsen’s correspondence became very scant, and we have no letters dating from the period when he was at work on

The Master Builder

. On the other hand, we possess a curious lyrical prelude to the play, which he put on paper on March 16, 1892. It is said to have been his habit, before setting to work on a play, to “crystallise in a poem the mood which then possessed him;” but the following is the only one of these keynote poems which has been published. I give it in the original language, with a literal translation:

DE SAD DER, DE TO —

De sad der, de to, i saa lunt et hus

ved host og i venterdage,

Saa braendte huset.

Alt ligger i grus.

De to faar i asken rage.

For nede id en er et smykke gemt, —

et smykke, som aldrig kan braende.

Og leder de trofast, haender det nemt

at det findes af ham eller hende.

Men finder de end, brandlidte to,

det dyre, ildfaste smykke, —

aldrig han finder sin braendte tro,

han aldrig sin braendte lykke.

THEY SAT THERE, THE TWO —

They sat there, the two, in so cosy a house, through autumn

and winter days.

Then the house burned down.

Everything

lies in ruins.

The two must grope among the ashes.

For among them is hidden a jewel — a jewel that never can burn.

And if they search faithfully, it may easily happen that he

or she may find it.

But even should they find it, the burnt-out two — find this

precious unburnable jewel — never will she find her burnt faith,

he never his burnt happiness.

This is the latest piece of Ibsen’s verse that has been given to the world; but one of his earliest poems — first printed in 1858 — was also, in some sort, a prelude to

The Master Builder

. Of this a literal translation may suffice. It is called,

BUILDING-PLANS

I remember as clearly as if it had been to-day the evening

when, in the paper, I saw my first poem in print.

There I

sat in my den, and, with long-drawn puffs, I smoked and I

dreamed in blissful self-complacency.

“I will build a cloud-castle.

It shall shine all over the

North.

It shall have two wings: one little and one great.

The great wing shall shelter a deathless poet; the little

wing shall serve as a young girl’s bower.”

The plan seemed to me nobly harmonious; but as time went on

it fell into confusion.

When the master grew reasonable, the

castle turned utterly crazy; the great wing became too little,

the little wing fell to ruin.

Thus we see that, thirty-five years before the date of

The Master Builder

, Ibsen’s imagination was preoccupied with a symbol of a master building a castle in the air, and a young girl in one of its towers.

There has been some competition among the poet’s young lady friends for the honour of having served as his model for Hilda. Several, no doubt, are entitled to some share in it. One is not surprised to learn that among the papers he left behind were sheaves upon sheaves of letters from women. “All these ladies,” says Dr. Julius Elias, “demanded something of him — some cure for their agonies of soul, or for the incomprehension from which they suffered; some solution of the riddle of their nature. Almost every one of them regarded herself as a problem to which Ibsen could not but have the time and the interest to apply himself. They all thought they had a claim on the creator of Nora.... Of this chapter of his experience, Fru Ibsen spoke with ironic humour. ‘Ibsen (I have often said to him), Ibsen, keep these swarms of over-strained womenfolk at arm’s length.’ ‘Oh no (he would reply), let them alone. I want to observe them more closely.’ His observations would take a longer or shorter time as the case might be, and would always contribute to some work of art.”

The principal model for Hilda was doubtless Fraulein Emilie Bardach, of Vienna, whom he met at Gossensass in the autumn of 1889. He was then sixty-one years of age; she is said to have been seventeen. As the lady herself handed his letters to Dr. Brandes for publication, there can be no indiscretion in speaking of them freely. Some passages from them I have quoted in the introduction to

Hedda Gabler

— passages which show that at first the poet deliberately put aside his Gossensass impressions for use when he should stand at a greater distance from them, and meanwhile devoted himself to work in a totally different key. On October 15, 1889, he writes, in his second letter to Fraulein Bardach: “I cannot repress my summer memories, nor do I want to. I live through my experiences again and again. To transmute it all into a poem I find, in the meantime, impossible. In the meantime? Shall I succeed in doing so some time in the future? And do I really wish to succeed? In the meantime, at any rate, I do not.... And yet it must come in time.” The letters number twelve in all, and are couched in a tone of sentimental regret for the brief, bright summer days of their acquaintanceship. The keynote is struck in the inscription on the back of a photograph which he gave her before they parted:

An die Maisonne eines Septemberlebens — in Tirol

,(1) 27/9/89. In her album he had written the words:

Hohes, schmerzliches Gluck —

um das Unerreichbare zu ringen!(2)

in which we may, if we like, see a foreshadowing of the Solness frame of mind. In the fifth letter of the series he refers to her as “an enigmatic Princess”; in the sixth he twice calls her “my dear Princess”; but this is the only point at which the letters quite definitely and unmistakably point forward to

The Master Builder

. In the ninth letter (February 6, 1890) he says: “I feel it a matter of conscience to end, or at any rate, to restrict, our correspondence.” The tenth letter, six months later, is one of kindly condolence on the death of the young lady’s father. In the eleventh (very short) note, dated December 30, 1890, he acknowledges some small gift, but says: “Please, for the present, do not write me again.... I will soon send you my new play

[

Hedda Gabler

]

. Receive it in friendship, but in silence!” This injunction she apparently obeyed. When

The Master Builder

appeared, it would seem that Ibsen did not even send her a copy of the play; and we gather that he was rather annoyed when she sent him a photograph signed “Princess of Orangia.” On his seventieth birthday, however, she telegraphed her congratulations, to which he returned a very cordial reply. And here their relations ended.

That she was right, however, in regarding herself as his principal model for Hilda appears from an anecdote related by Dr. Elias.(3) It is not an altogether pleasing anecdote, but Dr. Elias is an unexceptionable witness, and it can by no means be omitted from an examination into the origins of

The Master Builder

. Ibsen had come to Berlin in February 1891 for the first performance of

Hedda Gabler

. Such experiences were always a trial to him, and he felt greatly relieved when they were over. Packing, too, he detested; and Elias having helped him through this terrible ordeal, the two sat down to lunch together, while awaiting the train. An expansive mood descended upon Ibsen, and chuckling over his champagne glass, he said: “Do you know, my next play is already hovering before me — of course in vague outline. But of one thing I have got firm hold. An experience: a woman’s figure. Very interesting, very interesting indeed. Again a spice of the devilry in it.” Then he related how he had met in the Tyrol a Viennese girl of very remarkable character. She had at once made him her confidant. The gist of her confessions was that she did not care a bit about one day marrying a well brought-up young man — most likely she would never marry. What tempted and charmed and delighted her was to lure other women’s husbands away from them. She was a little daemonic wrecker; she often appeared to him like a little bird of prey, that would fain have made him, too, her booty. He had studied her very, very closely. For the rest, she had had no great success with him. “She did not get hold of me, but I got hold of her — for my play. Then I fancy” (here he chuckled again) “she consoled herself with some one else.” Love seemed to mean for her only a sort of morbid imagination. This, however, was only one side of her nature. His little model had had a great deal of heart and of womanly understanding; and thanks to the spontaneous power she could gain over him, every woman might, if she wished it, guide some man towards the good. “Thus Ibsen spoke,” says Elias, “calmly and coolly, gazing as it were into the far distance, like an artist taking an objective view of some experience — like Lubek speaking of his soul-thefts. He had stolen a soul, and put it to a double employment. Thea Elvsted and Hilda Wangel are intimately related — are, indeed only different expressions of the same nature.” If Ibsen actually declared Thea and Hilda to be drawn from one model, we must of course take his word for it; but the relationship is hard to discern.

There can be no reasonable doubt, then, that the Gossensass episode gave the primary impulse to

The Master Builder

. But it seems pretty well established, too, that another lady, whom he met in Christiania after his return in 1891, also contributed largely to the character of Hilda. This may have been the reason why he resented Fraulein Bardach’s appropriating to herself the title of “Princess of Orangia.”

The play was published in the middle of December 1892. It was acted both in Germany and England before it was seen in the Scandinavian capitals. Its first performance took place at the Lessing Theatre, Berlin, January 19, 1893, with Emanuel Reicher as Solness and Frl. Reisenhofer as Hilda. In London it was first performed at the Trafalgar Square Theatre (now the Duke of York’s) on February 20, 1893, under the direction of Mr. Herbert Waring and Miss Elizabeth Robins, who played Solness and Hilda. This was one of the most brilliant and successful of English Ibsen productions. Miss Robins was almost an ideal Hilda, and Mr. Waring’s Solness was exceedingly able. Some thirty performances were give in all, and the play was reproduced at the Opera Comique later in the season, with Mr. Lewis Waller as Solness. In the following year Miss Robins acted Hilda in Manchester. In Christiania and Copenhagen the play was produced on the same evening, March 8, 1893; the Copenhagen Solness and Hilda were Emil Poulsen and Fru Hennings. A Swedish production, by Lindberg, soon followed, both in Stockholm and Gothenburg. In Paris

Solness le constructeur

was not seen until April 3, 1894, when it was produced by “L’OEuvre” with M. Lugne-Poe as Solness. The company, sometimes with Mme. Suzanne Despres and sometimes with Mme. Berthe Bady as Hilda, in 1894 and 1895 presented the play in London, Brussels, Amsterdam, Milan, and other cities. In October 1894 they visited Christiania, where Ibsen was present at one of their performances, and is reported by Herman Bang to have been so enraptured with it that he exclaimed, “This is the resurrection of my play!” On this occasion Mme. Bady was the Hilda. The first performance of the play in America took place at the Carnegie Lyceum, New York, on January 16, 1900, with Mr. William H. Pascoe as Solness and Miss Florence Kahn as Hilda. The performance was repeated in the course of the same month, both at Washington and Boston.