Complete Works of Wilkie Collins (2151 page)

Read Complete Works of Wilkie Collins Online

Authors: Wilkie Collins

His father found him, one morning, when he was quite a lad, sitting before a little picture on which he had been engaged for some time, weeping over his inability to paint some tangled grass and weeds occupying the foreground of his composition, and only wanting to complete it. Effort after effort had been made, each less successful than the other, until at length he had abandoned his work in a fit of temporary despair. His father, with his usual kindness, took up the palette, and endeavoured to give some assistance; but with so little felicity, that the unfortunate piece of foreground looked worse than ever, under the treatment of the new hand; and as a last resource, he recommended his son to change the refractory object into a sand-bank, or a ditch, or a heap of old timber. The young student was not, however, of a disposition to retreat from a difficulty thus: he started up, dried his eyes, took his sketch- book, and left the house; returning in the evening with a drawing from Nature of a patch of grass, in which the position of every blade was separately copied. The next day he painted the foreground object he had designed with complete success, in a few hours; telling his father, when he showed him the finished picture, that he had been to Hampstead to make a study for his foreground, because he was determined never to strike out what he

wanted

to do, in his work, for the sake of putting in what he

could

do; and because he was ashamed to call himself a painter, as long as he was unable to paint grass as he ought.

His estimate of his own position and power in his pursuit was always free from the slightest influence of self-assumption; and his appreciation of the productions, and satisfaction at the success, of his contemporaries, was in all instances thoroughly generous and spontaneous. His presence — welcome everywhere — was particularly valued by the members of his profession; for they knew that his praise was disinterested, and his advice sincere. His grateful sense of the attention shown to his works was unalloyed by any passing feeling of discontent: he always believed that they had been duly appreciated both by the public and the patrons. To the general correctness of the settled judgment of the former, even where it might hardly agree with his own sentiments, he rarely demurred; and to the justice and liberality of the latter, he ever bore willing testimony. One of his greatest anxieties — as the reader already knows, from the perusal of his Journal for 1844 — was, that if ever his biography was written, one of its main objects should be the refutation, from his own case, of the thoughtless charges of neglect to contemporary native talent, too frequently preferred against the patrons of English Art.

His talents for society were varied and attractive in an uncommon degree. His rich vein of humour and anecdote, and his faculty of leading others imperceptibly to discuss the subjects which most interested them, fitted him to be the companion of men of widely differing mental peculiarities. His intellectual sympathies moved as harmoniously with the deliberative observation of Wilkie, as with the sensitive imagination of Allston. On one day the profound and philosophic Coleridge would sit by his easel, and pour forth mystic speculations to his attentive ear, — on another the happy retort or the brilliant jest was addressed to him, as to a congenial spirit, from the mirthful imagination of James Smith. Though much of his power of thus easily adapting his mind to the minds of others, and of attracting and preserving the steady friendship of men of opposite intellectual characters was attributable to his natural pliability of disposition, much must also be ascribed to his stores of information on general topics, by which he became fitted for the observation and discussion of other subjects besides his Art. His anxiety for knowledge, and his wish to contribute, as far as his own example would go, to maintain in the world a high character for his profession, led him at an early age to adopt such a judicious system of reading as should enable him to appear in society not only as an eminent painter, but also as an educated man.

Of other additional features in his social character which may require notice, a just estimate is formed in a paragraph of the “Art-Union Journal” for April, 1847, (inserted by another hand, to conclude a short memoir of his life, furnished by the writer of these pages,) which is well worthy of insertion, as displaying some evidence of the influence of his character on those whose personal intercourse with him gave them the capacity to judge it aright. The passage referred to is as follows:

“In common with all who personally knew Mr. Collins, we feel that we have lost a friend. His merits as an artist have been universally appreciated; but his intimate acquaintances only could rightly estimate the high qualities of his mind and heart; generous and encouraging to young talent, he was always eager to accord praise; neither jealousy nor envy ever gave the remotest taint to his character. Men of note in all professions were proud to be his associates, for he was fitted to take his place among the best of them: his gracious manner and most gentlemanly bearing. no less than his cultivated understanding, exciting the esteem and respect of all with whom he came in contact. It is not always that a public loss is a private affliction, — in that of Mr. Collins it is eminently so: for while no artist of our age and country has more largely contributed to uphold the importance and augment the dignity of the profession, no man was more thoroughly imbued with the gentle and kindly, yet manly, attributes which excite affection. In the Royal Academy, his absence will, we are sure, be keenly felt; for a nature such as his was peculiarly calculated to disarm animosity, soften down asperity, and carry conviction that measures which appear unwise, arbitrary, and selfish, were in reality designed to advance the general good.”

Of the measure in which the subject of this Memoir was possessed of that higher and nobler part of personal character, which religious principle and domestic affection compose; and to which it may appear, in conclusion, a duty to advert, it is above the province of the Author of this narrative to inquire or to judge. The numerous passages in the Journals and Letters that have been inserted in these pages, as displaying how invariably their writer guided the course of all his most cherished mortal hopes by the light of his religion; and how intimately the happiness of his social life was dependent on the influences of his home, afford the best, because the truest, criterion of his character. By their testimony, his religious convictions and his moral disposition stand displayed — through any other medium they could only be described.

Here, though more may yet remain to be told, the further progress of this work must cease; for if the purpose of its contents is to be answered at all, it is to be answered by what they already present. Whether the Design in which these Memoirs originated, and by which they have been introduced to the reader, has been duly fulfilled; and whether, should such be the case, it can be hoped, that in these times of fierce political contention, and absorbing political anxiety, they should be important enough to awaken the attention, or even to amuse the leisure of others, are doubts which cannot now be resolved; and which, could they be penetrated, I should at this stage of my undertaking be little willing to approach. In proportion as this work may contain what is valuable or true, will be its chance that what is imperfect in it may be forgotten, for the sake of what is useful that may be retained. I can therefore only conclude my undertaking with the hope that I have not so miscalculated my power of turning to some worthy account a daily observation of the intellectual habits, and an intimate connection with the social life of an eminent Painter, as not to have produced something that may be encouraging and instructive, as an example to the student of Art; and interesting, perhaps new, as the narrative of a pictorial career, to the general reader. My labours are closed.

OR

NOTES IN CORNWALL TAKEN A-FOOT.

First published 1851, this was n illustrated travel book narrating Collins’ 1850 walking tour of Cornwall with his artist friend, Henry Brandling.

RAMBLES BEYOND RAILWAYS.

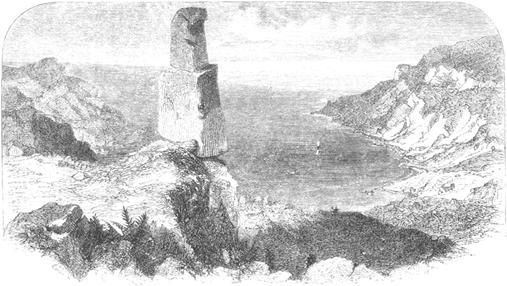

LAMORNA COVE.

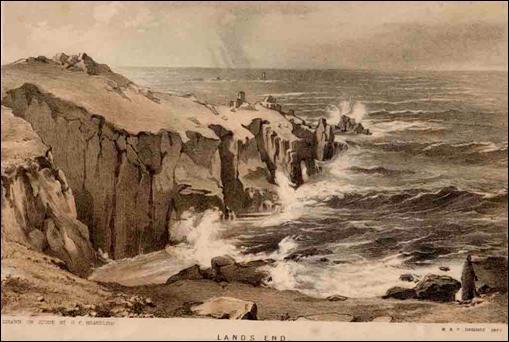

The Land’s End, Cornwall.

PREFACE

TO

THE PRESENT EDITION.

I visited Cornwall, for the first time, in the summer and autumn of 1850; and in the winter of the same year, I wrote this book.

At that time, the title attached to these pages was strictly descriptive of the state of the county, when my companion and I walked through it. But when, little more than a year afterwards, a second edition of this volume was called for, the all-conquering railway had invaded Cornwall in the interval, and had practically contradicted me on my own title-page.

To rechristen my work was out of the question — I should simply have destroyed its individuality. Ladies may, and do, often change their names for the better; but books enjoy no such privilege. In this embarrassing position, I ended by treating the ill-timed intrusion of the railway into my literary affairs, as a certain Abbé (who was also an author,) once treated the overthrow of the Swedish Constitution, in the reign of Gustavus the Third. Having written a profound work, to prove that the Constitution, as at that time settled, was secure from all political accidents, the Abbé was surprised in his study, one day, by the appearance of a gentleman, who disturbed him over the correction of his last proof-sheet. “Sir!” said the gentleman; “I have looked in to inform you that the Constitution has just been overthrown.” To which the Abbé replied: — ”Sir! they may overthrow the Constitution, but they can’t overthrow My Book” — and he quietly went on with his work.