Complete Works of Wilkie Collins (244 page)

Read Complete Works of Wilkie Collins Online

Authors: Wilkie Collins

Mr. Nixon, to whom Leonard immediately sent word of what had happened, volunteered to go to Bayswater the same evening, and make an attempt to see Mr. Treverton on Mr. and Mrs. Frankland’s behalf. He found Timon of London more approachable than he had anticipated. The misanthrope was, for once in his life, in a good humor. This extraordinary change in him had been produced by the sense of satisfaction which he experienced in having just turned Shrowl out of his situation, on the ground that his master was not fit company for him after having committed such an act of folly as giving Mrs. Frankland back her forty thousand pounds.

“I told him,” said Mr. Treverton, chuckling over his recollection of the parting scene between his servant and himself — ”I told him that I could not possibly expect to merit his continued approval after what I had done, and that I could not think of detaining him in his place under the circumstances. I begged him to view my conduct as leniently as he could, because the first cause that led to it was, after all, his copying the plan of Porthgenna, which guided Mrs. Frankland to the discovery in the Myrtle Room. I congratulated him on having got a reward of five pounds for being the means of restoring a fortune of forty thousand; and I bowed him out with a polite humility that half drove him mad. Shrowl and I have had a good many tussles in our time; he was always even with me till to-day, and now I’ve thrown him on his back at last!”

Although Mr. Treverton was willing to talk of the defeat and dismissal of Shrowl as long as the lawyer would listen to him, he was perfectly unmanageable on the subject of Mrs. Frankland, when Mr. Nixon tried to turn the conversation to that topic. He would hear no messages — he would give no promise of any sort for the future. All that he could be prevailed on to say about himself and his own projects was that he intended to give up the house at Bayswater, and to travel again for the purpose of studying human nature, in different countries, on a plan that he had not tried yet — the plan of endeavoring to find out the good that there might be in people as well as the bad. He said the idea had been suggested to his mind by his anxiety to ascertain whether Mr. and Mrs. Frankland were perfectly exceptional human beings or not. At present, he was disposed to think that they were, and that his travels were not likely to lead to anything at all remarkable in the shape of a satisfactory result. Mr. Nixon pleaded hard for something in the shape of a friendly message to take back, along with the news of his intended departure. The request produced nothing but a sardonic chuckle, followed by this parting speech, delivered to the lawyer at the garden gate.

“Tell those two superhuman people,” said Timon of London, “that I may give up my travels in disgust when they least expect it; and that I may possibly come back to look at them again — I don’t personally care about either of them — but I should like to get one satisfactory sensation more out of the lamentable spectacle of humanity before I die.”

THE DAWN OF A NEW LIFE.

FOUR days afterward, Rosamond and Leonard and Uncle Joseph met together in the cemetery of the church of Porthgenna.

The earth to which we all return had closed over Her: the weary pilgrimage of Sarah Leeson had come to its quiet end at last. The miner’s grave from which she had twice plucked in secret her few memorial fragments of grass had given her the home, in death, which, in life, she had never known. The roar of the surf was stilled to a low murmur before it reached the place of her rest; and the wind that swept joyously over the open moor paused a little when it met the old trees that watched over the graves, and wound onward softly through the myrtle hedge which held them all embraced alike in its circle of lustrous green.

Some hours had passed since the last words of the burial service had been read. The fresh turf was heaped already over the mound, and the old head-stone with the miner’s epitaph on it had been raised once more in its former place at the head of the grave. Rosamond was reading the inscription softly to her husband. Uncle Joseph had walked a little apart from them while she was thus engaged, and had knelt down by himself at the foot of the mound. He was fondly smoothing and patting the newly laid turf — as he had often smoothed Sarah’s hair in the long-past days of her youth — as he had often patted her hand in the after-time, when her heart was weary and her hair was gray.

“Shall we add any new words to the old, worn letters as they stand now?” said Rosamond, when she had read the inscription to the end. “There is a blank space left on the stone. Shall we fill it, love, with the initials of my mother’s name, and the date of her death? I feel something in my heart which seems to tell me to do that, and to do no more.”

“So let it be, Rosamond,” said her husband. “That short and simple inscription is the fittest and the best.”

She looked away, as he gave that answer, to the foot of the grave, and left him for a moment to approach the old man. “Take my hand, Uncle Joseph,” she said, and touched him gently on the shoulder. “Take my hand, and let us go back together to the house.”

He rose as she spoke, and looked at her doubtfully. The musical box, inclosed in its well-worn leather case, lay on the grave near the place where he had been kneeling. Rosamond took it up from the grass, and slung it in the old place at his side, which it had always occupied when he was away from home. He sighed a little as he thanked her. “Mozart can sing no more,” he said. “He has sung to the last of them now!”

“Don’t say ‘to the last,’ yet,” said Rosamond, “don’t say ‘to the last,’ Uncle Joseph, while I am alive. Surely Mozart will sing to me, for my mother’s sake?”

A smile — the first she had seen since the time of their grief — trembled faintly round his lips. “There is comfort in that,” he said; “there is comfort for Uncle Joseph still, in hearing that.”

“Take my hand,” she repeated softly. “Come home with us now.”

He looked down wistfully at the grave. “I will follow you,” he said, “if you will go on before me to the gate.”

Rosamond took her husband’s arm, and guided him to the path that led out of the churchyard. As they passed from sight, Uncle Joseph knelt down once more at the foot of the grave, and pressed his lips on the fresh turf.

“Good-by, my child,” he whispered, and laid his cheek for a moment against the grass before he rose again.

At the gate, Rosamond was waiting for him. Her right hand was resting on her husband’s arm; her left hand was held out for Uncle Joseph to take.

“How cool the breeze is!” said Leonard. “How pleasantly the sea sounds! Surely this is a fine summer day?”

“The calmest and loveliest of the year,” said Rosamond. “The only clouds on the sky are clouds of shining white; the only shadows over the moor lie light as down on the heather. Oh, Lenny, it is such a different day from that day of dull oppression and misty heat when we found the letter in the Myrtle Room! Even the dark tower of our old house, yonder, looks its brightest and best, as if it waited to welcome us to the beginning of a new life. I will make it a happy life to you, and to Uncle Joseph, if I can — happy as the sunshine we are walking in now. You shall never repent, love, if I can help it, that you have married a wife who has no claim of her own to the honours of a family name.”

“I can never repent my marriage, Rosamond, because I can never forget the lesson that my wife has taught me.”

“What lesson, Lenny?”

“An old one, my dear, which some of us can never learn too often. The highest honours, Rosamond, are those which no accident can take away — the honours that are conferred by LOVE and TRUTH.”

THE END

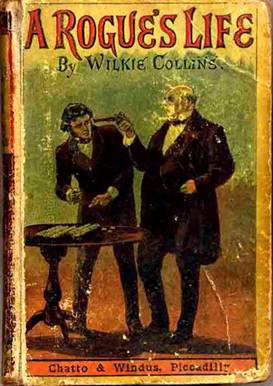

This short novel was originally published in

Household Words

in 1856.

It was republished in book form in 1879 after an invitation from George Bentley ‘to take a place in his new series of pretty volumes in red.’

Collins made minor changes to the text and noted in some ‘Introductory Words’ that it was written ‘at a very happy time in my past life...at Paris, when I had Charles Dickens for a near neighbour and a daily companion.’

He also revealed that he had intended, but never written, a further series of the Rogue’s adventures in Australia.

It tells the story of

Frank Softly, a poor young gentleman whose snobbish father sends him to boarding school to make useful connections, yet without success. He tries a variety of professions to earn his living but by the time he is 25 has failed at medicine, caricaturing, portrait painting, forging Old Masters and administering a scientific institution.

The 1890 Chatto & Windus edition

A ROGUE’S LIFE

CONTENTS