Complete Works of Wilkie Collins (367 page)

Read Complete Works of Wilkie Collins Online

Authors: Wilkie Collins

“I am afraid he has brought you bad news?”

“Horrible news, Walter! Let us go back to London — I don’t want to stop here — I am sorry I ever came. The misfortunes of my youth are very hard upon me,” he said, turning his face to the wall, “very hard upon me in my later time. I try to forget them — and they will not forget ME!”

“We can’t return, I am afraid, before the afternoon,” I replied. “Would you like to come out with me in the meantime?”

“No, my friend, I will wait here. But let us go back to-day — pray let us go back.”

I left him with the assurance that he should leave Paris that afternoon. We had arranged the evening before to ascend the Cathedral of Notre Dame, with Victor Hugo’s noble romance for our guide. There was nothing in the French capital that I was more anxious to see, and I departed by myself for the church.

Approaching Notre Dame by the river-side, I passed on my way the terrible dead-house of Paris — the Morgue. A great crowd clamoured and heaved round the door. There was evidently something inside which excited the popular curiosity, and fed the popular appetite for horror.

I should have walked on to the church if the conversation of two men and a woman on the outskirts of the crowd had not caught my ear. They had just come out from seeing the sight in the Morgue, and the account they were giving of the dead body to their neighbours described it as the corpse of a man — a man of immense size, with a strange mark on his left arm.

The moment those words reached me I stopped and took my place with the crowd going in. Some dim foreshadowing of the truth had crossed my mind when I heard Pesca’s voice through the open door, and when I saw the stranger’s face as he passed me on the stairs of the hotel. Now the truth itself was revealed to me — revealed in the chance words that had just reached my ears. Other vengeance than mine had followed that fated man from the theatre to his own door — from his own door to his refuge in Paris. Other vengeance than mine had called him to the day of reckoning, and had exacted from him the penalty of his life. The moment when I had pointed him out to Pesca at the theatre in the hearing of that stranger by our side, who was looking for him too — was the moment that sealed his doom. I remembered the struggle in my own heart, when he and I stood face to face — the struggle before I could let him escape me — and shuddered as I recalled it.

Slowly, inch by inch, I pressed in with the crowd, moving nearer and nearer to the great glass screen that parts the dead from the living at the Morgue — nearer and nearer, till I was close behind the front row of spectators, and could look in.

There he lay, unowned, unknown, exposed to the flippant curiosity of a French mob! There was the dreadful end of that long life of degraded ability and heartless crime! Hushed in the sublime repose of death, the broad, firm, massive face and head fronted us so grandly that the chattering Frenchwomen about me lifted their hands in admiration, and cried in shrill chorus, “Ah, what a handsome man!” The wound that had killed him had been struck with a knife or dagger exactly over his heart. No other traces of violence appeared about the body except on the left arm, and there, exactly in the place where I had seen the brand on Pesca’s arm, were two deep cuts in the shape of the letter T, which entirely obliterated the mark of the Brotherhood. His clothes, hung above him, showed that he had been himself conscious of his danger — they were clothes that had disguised him as a French artisan. For a few moments, but not for longer, I forced myself to see these things through the glass screen. I can write of them at no greater length, for I saw no more.

The few facts in connection with his death which I subsequently ascertained (partly from Pesca and partly from other sources), may be stated here before the subject is dismissed from these pages.

His body was taken out of the Seine in the disguise which I have described, nothing being found on him which revealed his name, his rank, or his place of abode. The hand that struck him was never traced, and the circumstances under which he was killed were never discovered. I leave others to draw their own conclusions in reference to the secret of the assassination as I have drawn mine. When I have intimated that the foreigner with the scar was a member of the Brotherhood (admitted in Italy after Pesca’s departure from his native country), and when I have further added that the two cuts, in the form of a T, on the left arm of the dead man, signified the Italian word “Traditore,” and showed that justice had been done by the Brotherhood on a traitor, I have contributed all that I know towards elucidating the mystery of Count Fosco’s death.

The body was identified the day after I had seen it by means of an anonymous letter addressed to his wife. He was buried by Madame Fosco in the cemetery of Pere la Chaise. Fresh funeral wreaths continue to this day to be hung on the ornamental bronze railings round the tomb by the Countess’s own hand. She lives in the strictest retirement at Versailles. Not long since she published a biography of her deceased husband. The work throws no light whatever on the name that was really his own or on the secret history of his life — it is almost entirely devoted to the praise of his domestic virtues, the assertion of his rare abilities, and the enumeration of the honours conferred on him. The circumstances attending his death are very briefly noticed, and are summed up on the last page in this sentence — ”His life was one long assertion of the rights of the aristocracy and the sacred principles of Order, and he died a martyr to his cause.”

III

The summer and autumn passed after my return from Paris, and brought no changes with them which need be noticed here. We lived so simply and quietly that the income which I was now steadily earning sufficed for all our wants.

In the February of the new year our first child was born — a son. My mother and sister and Mrs. Vesey were our guests at the little christening party, and Mrs. Clements was present to assist my wife on the same occasion. Marian was our boy’s godmother, and Pesca and Mr. Gilmore (the latter acting by proxy) were his godfathers. I may add here that when Mr. Gilmore returned to us a year later he assisted the design of these pages, at my request, by writing the Narrative which appears early in the story under his name, and which, though first in order of precedence, was thus, in order of time, the last that I received.

The only event in our lives which now remains to be recorded, occurred when our little Walter was six months old.

At that time I was sent to Ireland to make sketches for certain forthcoming illustrations in the newspaper to which I was attached. I was away for nearly a fortnight, corresponding regularly with my wife and Marian, except during the last three days of my absence, when my movements were too uncertain to enable me to receive letters. I performed the latter part of my journey back at night, and when I reached home in the morning, to my utter astonishment there was no one to receive me. Laura and Marian and the child had left the house on the day before my return.

A note from my wife, which was given to me by the servant, only increased my surprise, by informing me that they had gone to Limmeridge House. Marian had prohibited any attempt at written explanations — I was entreated to follow them the moment I came back — complete enlightenment awaited me on my arrival in Cumberland — and I was forbidden to feel the slightest anxiety in the meantime. There the note ended. It was still early enough to catch the morning train. I reached Limmeridge House the same afternoon.

My wife and Marian were both upstairs. They had established themselves (by way of completing my amazement) in the little room which had been once assigned to me for a studio, when I was employed on Mr. Fairlie’s drawings. On the very chair which I used to occupy when I was at work Marian was sitting now, with the child industriously sucking his coral upon her lap — while Laura was standing by the well-remembered drawing-table which I had so often used, with the little album that I had filled for her in past times open under her hand.

“What in the name of heaven has brought you here?” I asked. “Does Mr. Fairlie know —

— ?”

Marian suspended the question on my lips by telling me that Mr. Fairlie was dead. He had been struck by paralysis, and had never rallied after the shock. Mr. Kyrle had informed them of his death, and had advised them to proceed immediately to Limmeridge House.

Some dim perception of a great change dawned on my mind. Laura spoke before I had quite realised it. She stole close to me to enjoy the surprise which was still expressed in my face.

“My darling Walter,” she said, “must we really account for our boldness in coming here? I am afraid, love, I can only explain it by breaking through our rule, and referring to the past.”

“There is not the least necessity for doing anything of the kind,” said Marian. “We can be just as explicit, and much more interesting, by referring to the future.” She rose and held up the child kicking and crowing in her arms. “Do you know who this is, Walter?” she asked, with bright tears of happiness gathering in her eyes.

“Even MY bewilderment has its limits,” I replied. “I think I can still answer for knowing my own child.”

“Child!” she exclaimed, with all her easy gaiety of old times. “Do you talk in that familiar manner of one of the landed gentry of England? Are you aware, when I present this illustrious baby to your notice, in whose presence you stand? Evidently not! Let me make two eminent personages known to one another: Mr. Walter Hartright — THE HEIR OF LIMMERIDGE.”

So she spoke. In writing those last words, I have written all. The pen falters in my hand. The long, happy labour of many months is over. Marian was the good angel of our lives — let Marian end our Story.

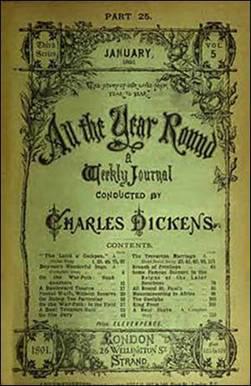

This 1862 novel focuses upon the issue of illegitimacy. Originally serialised in Charles Dickens’ magazine

All the Year Round

, the story begins in 1846 in West Somersetshire, the country residence of the happy Vanstone family. When Andrew Vanstone is killed suddenly in an accident and his wife follows shortly thereafter, it is revealed that they were not married at the time of their daughters’ births, making their daughters “Nobody’s Children” in the eyes of English law and robbing them of their inheritance. Andrew Vanstone’s elder brother Michael gleefully takes possession of his brother’s fortune, leaving his nieces to make their own way in the world. Norah, the elder sister, accepts her misfortune gracefully, but the headstrong Magdalen is determined to have her revenge. Using her dramatic talent and assisted by wily swindler Captain Wragge, Magdalen plots to regain her rightful inheritance.

A copy of the magazine in which the novel first appeared