Constant Touch (11 page)

Authors: Jon Agar

Tags: #science, #engineering and technology, #telecommunications, #electronics and communications, #telephone and wireless technology, #internet, #mobile telephones

Of much greater significance was the adoption of the International Mobile Equipment Identity (IMEI) code. While the SIM card would be tied to the person, the fifteen-digit IMEI number was tied to the device. Try it yourself. Tap in *#06# and, on almost all cellphones, your IMEI will be displayed. (Why not write it down now in a safe place!) If a phone is stolen then it can be blocked by using the IMEI to disable the SIM card. Unblocking â the changing of a IMEI number, quite different from the harmless âunlocking' which frees a phone from being tied to one company's service â by anyone other than manufacturers is illegal in most countries.

Meanwhile the information held by mobile phone operators, and even the personal data stored on the SIM card, have become detective tools and forensic evidence. In 1993, the hiding place of the cocaine baron Pablo Escobar was found by tracking his mobile radio calls. In October 2002, similar surveillance probably contributed to the arrest of al-Qaeda suspect Abu

Qatada. In 2010 the chance eavesdropping of the cellphone of Osama bin Laden's courier, Ibrahim Saeed Ahmed, led American investigators to the Peshawar district of Pakistan. Further intensive, and deeply secretive, probing located the al-Qaeda leader's compound in Abbotabad. Navy SEALS shot bin Laden dead in a raid on 2Â May 2011.

Just one other, less serious example must serve as an illustration. In July 2001, after four years on the run, the authorities finally caught up in the Philippines with Alfred Sirven, a French businessman wanted as part of the investigations into the Elf Aquitaine corruption scandal. At the moment of arrest, Sirven realised the potentially incriminating evidence he held on his person. James Tasoc, of the National Bureau of Investigation in the Philippines, described what happened next: âHe munched up the chip of his mobile like chewing gum. He broke it with his teeth.'

While the uses of mobile phones for criminal activity and detection are revealing, we should not forget a much more everyday role: many mobile phones are carried as part of the complex strategies that we all develop of dealing with the risks and dangers of modern life. So a phone is bought by parents for a son or daughter who is leaving home as a student, or for a teenager who is starting to stay out late at night, as an act of reassurance: should they ever be in trouble, they will not lack the means of contact. The diminishing guardianship of

family life is replaced by the constant touch of the mobile phone. Again, the fear of car breakdowns in remote places has often been cited by women as a major reason for owning a cellphone. (Notice how the two technologies of mobility interact again.) Likewise, in countries such as Sweden, the United Kingdom or Germany, where most of the population already own a mobile phone, further expansion of the market has depended on sales pitches that play on fear. Early adopters of the mobile needed little persuasion, and the young took to the chatty communicability of mobile phones like ducks to water. But selling to an older market, which can be either more technophobic or wiser in their purchases, has relied on presenting the mobile phone as a safety technology of last resort. This was why my parents bought one. While anyone who has been saved a walk along the hard shoulder of a motorway at night to find a landline telephone will know the true benefits of the mobile phone as a tool of safety, sometimes the device seems to be merely talismanic. Like a statuette of St Christopher, possession alone seems to ward off danger. A colleague of mine tells a story of one of his parents, who carried a mobile phone in their car. On one occasion a passenger needed to make a phone call and asked to use the mobile. Unsure about the method of operation, the passenger enquired how to work it. âOh, I don't know,' came the reply. âI always have it turned off. It's only for emergencies.'

Women

were targeted in mobile phone advertising in the 1980s. Note how âpeace of mind' is promised if âyou're always in touch'. However, exploiting fear of crime was an old tactic, as the next illustration demonstrates. (BTÂ Archives)

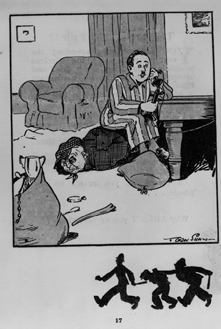

âWhy aren't YOU on the phone?', issued by the telephone development association, c. 1905 â evidence that fear of crime has been used to sell telephones since the early days. Thank heavens that âobliging constables' would save us from âmarauding humanity'! (BT Archives)

Phone hacking: a very British scandal

The

full extent of phone hacking in Britain only became apparent in 2011 when a full-blown controversy over illegal practices broke out. What was revealed was a queasy and disturbing set of relationships between newspapers, celebrities, politicians and police. It started, as with the earlier case of Princess Diana's âSquidgy' tapes, with royalty. In November 2005, the

News of the World

, a Sunday tabloid which was part of Rupert Murdoch's News International empire, the biggest-selling newspaper in the country and jocularly known as

News of the Screws

for its coverage of salacious gossip, published a story on Prince William's injured knee. Buckingham Palace suspected phone hacking as the source of the story and called in the police. In 2006 the newspaper's royal editor, Clive Goodman, and its private investigator Glenn Mulcaire, suspected of doing the dirty work, were arrested and charged. For many months the newspaper held the line that this was a limited case of rogue reporting. A perfunctory police investigation seemed to confirm this account. In the meantime Andy Coulson, the then editor of the

News of the World

was appointed as the new prime minister David Cameron's director of communications and planning.

However,

by 2010 it was clear that many celebrities, national figures and others had had their phones hacked in the early- to mid-2000s. In the analogue days of the Squidgy tapes this would have been done by simply eavesdropping using radio scanners. In the second-generation, digital era of mobile phones the hacking was typically achieved by targeting voicemail, exploiting the fact that many people did not change the factory settings of PINs (â1234', for example). A complementary technique was known as âdouble whacking', in which one person engaged a phone number while another person rang in; the second caller would be directed to the voicemail account, which could then be hacked. Mulcaire specialised in the use of another method: he called phone service providers using a unique retrieval number and then used a new PIN.

A small industry of private investigators grew up from the late 1990s, hacking voicemails and selling the information on to willing journalists. One journalist, James Hipwell, who worked the City Desk, located next to the showbiz journalists, on the

Daily Mirror

, described phone hacking as a âbog-standard journalistic tool for gathering information'. Dominic Mohan, showbusiness editor of the

Sun

, even jokily thanked Vodafone's âlack of security' during a speech to other members of the press. Nevertheless this was insider knowledge that stood in stark contrast to public denial that the practice was widespread, or anything more than

a ârogue reporter'. Despite repeated attempts to bury the story, in mid-2011, parliamentary questioning â led by Labour MP Tom Watson and investigative journalism by the

Guardian

and the

New York Times

â uncovered the shocking extent of the misdeeds. Hacking was one of a number of so-called âblack arts', that also extended to such practices as âblagging' (the impersonation of others in order to secure personal information), bribery and harassment. The suspicions hinted at collusion at high levels between senior News International executives, journalists and editors, private investigators and senior police officers. The tipping point came in July 2011 when it was claimed that the murdered schoolgirl Milly Dowler's phone had been hacked â and, it seemed, voicemails deleted, offering cruel and false hope to her parents. Coulson and Rebekah Brooks, chief executive of News International and former editor of the

News of the World

, were forced to resign. The

News of the World

, with advertisers deserting, folded. The last edition, on 7 July 2011, confessed in an editorial âQuite simply, we lost our way ⦠Phones were hacked, and for that this newspaper is truly sorry.'

The phone-hacking scandal prompted a wide-ranging inquiry into press ethics, chaired by Lord Leveson, which began in November 2011. A host of witnesses were brought forward and their testimony recorded and probed. The public heard âhow the details of private lives, known only to the witnesses testifying (in other words, the

targets of voicemail hacking) and their most trusted confidants and friends, became the subject of articles in the press', while through the technique of voicemail hacking âjournalists and press photographers were able to record moments that were intensely private, such as relationship breakdown, or family grief'. Sienna Miller, star of

Layer Cake

and

Factory Girl

,

explained [to the Leveson Inquiry] how she was the subject of many articles either speculating on or reporting the state of her relationship with the actor Jude Law. In many cases, the information that had formed the basis of these articles had been known only to Ms Miller, Mr Law and a very small number of confidants who had not shared the information further. Ms Miller gave a graphic description of the fall-out from the voicemail hacking which News International has, of course, admitted took place. This included the corrosive loss of trust in aspects of family life, in relationships and in friendships, Ms Miller assuming, understandably, that her inner circle was the source of stories in the press. She described herself as âtorn between feeling completely paranoid that either someone close to [her] (a trusted family member or friend) was selling this information to the media or that someone was somehow hacking [her] telephone.'

These

expressions of feelings of violation, anxiety and intrusion were echoed in other testimony, not only from celebrities:

Although the targets included a large number of celebrities, sports stars and people in positions of responsibility, they also included many other ordinary individuals who happened to know a celebrity or sports star, or happened to be employed by them. Other victims had no association with anyone in the public eye at all, but were, like the Dowlers, in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Leveson finally reported his findings and recommendations in November 2012. Even then Leveson's weighty tome â a full 1,987 pages â drew back from full disclosure of many of the cases of alleged phone interception in order not to prejudice ongoing criminal proceedings. While Leveson noted that âit is still not clear just how widespread the practice of phone hacking was, or the extent to which it may have extended beyond one title; and, in the light of the limitations which necessarily impact on this aspect of the Inquiry because of the ongoing investigation and impending prosecutions, it is simply not possible to be definitive', nevertheless the evidence presented âpoints to phone hacking being a common and known practice at the NoTW and elsewhere'. On the specific case of

the Milly Dowler phone the facts remained murky. The phone had certainly been hacked and presumably voicemails listened to. But the deletions, which raised false hopes and were the direct cause of the spike in public revulsion of the practice of phone hacking, may have been caused by something as simple as a technical system update. Nevertheless, on the behaviour of the

News of the World

, Leveson spoke brutally:

In truth, at no stage did anybody drill down into the facts to answer the myriad of questions that could have been asked and which could be encompassed by the all-embracing question âWhat the hell was going on?' These questions included what Mr Mulcaire had been doing for such rewards and for whom; what oversight had been exercised in relation to the use of his services; why had Mr Goodman felt it justifiable to involve himself in phone hacking; why had he argued that he should be able to return to employment and why was he being (or why had [he] been) paid off. On any showing, these questions were there to be asked and simple denials should not have been considered sufficient. This suggests a cover-up by somebody and at more than one level. Although this conclusion might be parsiÂmonious, it is more than sufficient to throw clear light on the culture, practices and ethics existing and

operating at the

News of the World

at the material time.

Throughout the same period and, as far as is known, entirely unconnected with the phone-hacking scandal, the surveillance of mobile phone records by the British secret state had increased; this took place legally and, one hopes, under ultimate political control. Occasional glimpses can be made of this shadowy world. For example, in 2008 it was revealed that the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ, the United Kingdom's electronic intelligence agency) recorded mobile phone exchanges between the Omagh bombers, responsible for a devastating explosion in a Northern Irish town, in 1998. In the 2000s there existed a voluntary agreement that mobile companies would store details of times, dates, duration and location of calls, as well as websites visited and email addresses used, for twelve months. The data were made available to police and security services. Indeed the then Home Secretary, Jacqui Smith, claimed that âdata about calls ⦠is used as important evidence in 95 per cent of serious crime cases and almost all security service operations since 2004'. From 2008 there have been attempts to push legislation through Parliament that would make such surveillance compulsory and extend its reach.

Of course, if the bulk of the British population â celebs as well as civilians â had not been in the habit of keeping

in constant touch then surveillance, either by opportunistic crooks or by authorised guardians of collective security, would not be worthwhile. The ubiquity of mobile phones was the first condition that made the phone-hacking scandal possible. But a second point relates to our intimate relationship with this personal technology. We use cellphones as if in a private bubble, even when in public. It is a double shock when our calls, made in private spaces, are eavesdropped. âWhile phone hacking itself is a “silent crime” inasmuch as the victim will usually be unaware of, or not even suspect, the covert assault on his or her privacy', noted Leveson, âits consequences â both direct and indirect â have often been serious and wide-ranging'. The force of this assault is directly in proportion to our mistaken sense of privacy.