Contested Will (17 page)

Authors: James Shapiro

Delia Bacon had more to fear from William Smith, an Englishman. Shortly after her

Putnam's

piece appeared in 1856 Smith published a brief pamphlet,

Was Lord Bacon the Author of

Shakespeare's

Plays, in which he argued that the plays pointed to the life of Bacon, not Shakespeare: âThe history of Bacon is just such as we should have drawn of Shakespeare, if we had been required to depict him from the internal evidence of his works.' Smith elaborated on this a year later in a book,

Bacon and Shakespeare

, which claimed, among other things, that the plays were meant to be read, not staged; that the Sonnets were autobiographical

(and pointed to Francis Bacon's early life); that a comparison of the works of Bacon and Shakespeare showed striking similarities; and that the works were a product of an aristocrat whose âdaily walk, letters, and conversation, constitute the beau ideal of such a man as we might suppose the author of the plays to have been'.

Accusations flew that Smith had stolen Delia Bacon's conclusions. Hawthorne, in introducing Bacon's book in 1857, intimated as much. Smith wrote to Hawthorne protesting how wrong this was, and Hawthorne wrote back, apologising. But the

Athenaeum

, which had run a piece as early as March 1855 paraphrasing an account of Delia Bacon's ideas that had recently appeared in Norton's

Literary Gazette

of New York, asked incredulously, âWill Mr. Smith assert that up to September 1856 he was unacquainted with Miss Bacon's theory? If so, we will make another assertion: namely, that Mr. Smith was the only man in England pretending to Shakespeare lore who enjoyed that amount of happy ignorance.' Smith responded that he had been thinking along these lines for some years. He probably had. But it's highly unlikely that Smith's pamphlet or book would have generated anywhere near the kind of interest that Bacon's article and book did â not only because Bacon had behind her some very powerful and visible literary figures, but also because her work (far more than his) was swept along on the powerful tide of the Higher Criticism.

With Hawthorne's quiet subvention

The Philosophy of the Plays of Shakspere Unfolded

, a rambling and almost unreadable book, was at last published in 1857, with five hundred copies for sale in England and another five hundred shipped over to America. The impossibly long title she had earlier proposed to her publishers was scrapped, though it more accurately conveys her argument:

The Advancement of Learning to Its True Sphere as Propounded by Francis Bacon and Other Writers of the Globe School, including the Part of Sir Walter Ralegh

. Hawthorne had been unable to prevail upon her to submit to editing (âMiss Bacon', he later wrote, âthrust the whole bulk of inspiration and nonsense into the press in a

lump; and there tumbled out a ponderous octavo volume, which fell with a dead thump at the feet of the public'). It was the last thing Delia Bacon would ever publish and the first that bore her name. Her plans to remain in England for another year âto prosecute the subject in a very different manner from any that I have been able to adopt hitherto' in âorder to make my second volume sustain the promise of this' were never realised. Her health, both mental and physical, had declined markedly during the previous year or so, much of it spent impoverished and in isolation. Shortly after the book came out she lost her wits, was briefly institutionalised in Warwickshire and then brought home to America, where she spent the last two years of her life in an asylum.

While Bacon had Hawthorne to thank for seeing her book at last into print, it was Hawthorne who unfortunately shaped for posterity the unshakable image of Bacon as a madwoman in the attic, a gothic figure who might have stepped out of the pages of his fiction. In 1863 he published an essay about her, âMemories of a Gifted Woman', that left readers with an indelible image of Delia Bacon haunting Shakespeare's grave, eager to unearth the long sought-for evidence that would prove her theory once and for all, daring the warning carved on Shakespeare's gravestone, âcurst be he that moves my bones':

Groping her way up the aisle and towards the chancel, she sat down on the elevated part of the pavement above Shakespeare's grave. If the divine poet really wrote the inscription there, and cared as much about the quiet of his bones as its deprecatory earnestness would imply, it was time for those crumbling relics to bestir themselves under her sacrilegious feet. But they were safe. She made no attempt to disturb them; though, I believe, she looked narrowly into the crevices between Shakespeare's and the two adjacent stones, and in some way satisfied herself that her single strength would suffice to lift the former, in case of need. She threw the feeble ray of her lantern up towards the bust, but could not make it visible beneath the darkness of the vaulted roof. Had she been subject to superstitious terrors, it is impossible to conceive of a situation that could better entitle her to feel them, for if Shakespeare's

ghost would rise at any provocation, it must have shown itself then; but it is my sincere belief, that, if his figure appeared within the scope of her dark lantern, in his slashed doublet and gown, and with his eyes bent on her beneath the high, bald forehead, just as we see him in the bust, she would have met him fearlessly and controverted his claims to the authorship of the plays, to his very face.

Hawthorne didn't know it, but Bacon had designs not only on Shakespeare's grave but also upon his monument. She would have taken that secret to the grave had she not confided in her brother, who then shared this bit of information with her physician: âher hallucination about Shakespeare has been, I believe, constant'. He adds:

She believes then, I suppose, believes now that the old tomb in the Church at Stratford-on-Avon, if she could be persuaded to take it down, would give conclusive evidence that the authorship of those plays which have been the world's admiration belong to Lord Bacon, Sir Walter Ralegh, and others, and withal a key to the hidden meaning of the Shakespearean Scriptures.

In this respect, too, she would anticipate future tomb-raiders eager to prove that someone other than Shakespeare had written the plays.

Shakespeare scholars have too often found it more convenient to invoke Hawthorne's gothic vision than to take seriously Emerson's posthumous verdict: âOur wild Whitman ⦠and Delia Bacon, with genius, but mad ⦠are the sole producers that America has yielded in ten years.' It was easier to dismiss her as a madwoman (this âeccentric American spinster' really â

was

mad', Samuel Schoenbaum insisted), one who led MacWhorter on, and us too, than to admit that she had merely taken mainstream assumptions and biographical claims a step or two further â albeit a dangerously mistaken one â than the scholars themselves had been willing to go. The intensity of the personal attacks begs the question of what was so threatening about her. Schoenbaum called Delia Bacon the first of the deviants â a term rich in religious,

psychological, even sexual connotations. Perhaps it wasn't her difference that proved so unnerving, but rather the extent to which her theory built on shared, if unspoken, beliefs.

One of these had to do with the extent to which the personality and temperament of the author of

The Tempest

closely resembled that of Francis Bacon. One of the last things Delia Bacon wrote was an unpublished âauthor's apology and claim', now, along with most of her surviving letters and papers, housed in the Folger Shakespeare Library. The long and rambling essay ends with Horatio's words to a dying Hamlet and a hopeful declaration: âRest Rest, perturbed spirit! Delia Bacon. Stratford-on-Avon. The Shakespeare Problem Solved.' But it is

The Tempest

that powerfully holds her imagination in this, her own version of Prospero's great speech on how âour revels now are ended':

The solving of these enigmas, the unraveling of this work, is going to make work and sport for us all; it is going to make a name â a scientific name, a common name, and a proper name, for us all. The name for us each, and the name for us all, scientifically defined, is at the bottom of it. We shall never solve the enigma, we shall never read these plays, till we come to that. â

Untie the spell

' is the word. That is the word on the

Isle of Prosper-O

, that magic isle ⦠This discovery was not made, could not have been made, by one impatient for the world's acknowledgements, or by one who loved best, or prized most, the sympathy, the approbation, or â the wisdom of the living. It was made, it had to be, by one instructed, not theoretically only, in the esoteric doctrine of the Elizabethan Age.

Her words and Prospero's â and, for her, Francis Bacon's â merge, are one. Delia Bacon had concluded her great task. She had also touched upon something that deeply resonated with many Victorian readers, a sense that the personality of the author of this last great play was much like that of the serene, learned, bookish Francis Bacon.

Hawthorne famously claimed of

The Philosophy of the Plays of Shakspere Unfolded

that âit has been the fate the of this remarkable book never to have had more than a single reader'. He was wrong.

Within a year of its publication and the dissemination of its argument in reviews and newspapers in England, Europe and the United States, the Baconian movement became international, with writers weighing in on the controversy in India, South Africa, France, Sweden, Serbia, Germany, Denmark, Poland, Austria, Italy, Hungary, Holland, Russia and Egypt. Word spread as far as the Mississippi River, where a pair of riverboat pilots vigorously argued the merits of Delia Bacon's case against Shakespeare. One of the pilots moved by her arguments was a young man named Samuel Clemens, soon to be known to the world by his pseudonym, Mark Twain.

On a chilly Friday afternoon in early January 1909, Mark Twain awaited a trio of weekend guests at Stormfield, his home in Redding, Connecticut. Twain had recently turned seventy-three. Though still spry, he was not in the best of health. He was a widower, his wife and best critic, Livia, having died five years earlier. Isabel Lyon, his forty-five-year-old secretary, did her best to fill Livia's place, while keeping Twain's two surviving children, Clara and Jean, distant from their father and Stormfield. Instead of family, the ageing Twain was surrounded by a doting secretary, a business manager, a resident biographer, stenographers and housekeepers â a host of retainers who called him, with no hint of irony, âthe King'. It cost a lot to maintain this entourage, which meant that Twain, who kept losing money on disastrous business ventures, then earning it back from books and lectures, had to keep writing.

A great final project continued to elude him; there would be no transcendent âlate phase' to his artistic career. Twain's best work, for which he hoped to be remembered, was becoming a thing of the increasingly distant past. His first bestseller,

The Innocents Abroad

, had been published forty years earlier. The torrent of great works that followed â including

Tom Sawyer

in 1876,

The Prince

and the Pauper

in 1881,

Life on the Mississippi

in 1883,

The

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

in 1884,

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court

in 1889 and

Pudd'nhead Wilson

in 1894 â had, by century's end, slowed to a trickle.

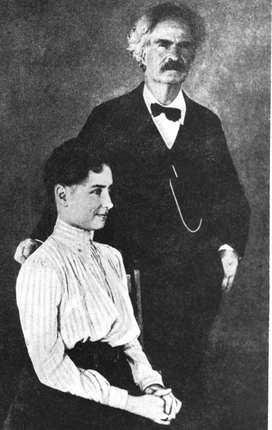

Helen Keller and Mark Twain, 1902, photograph by E. C. Kopp

Searching for something to write about, Twain turned to the subject he knew best, one that had always been at the centre of his fictional world: himself. He had been experimenting with autobiography for decades and now seized on a new approach, a kind of free association, recorded by a stenographer: âStart at no particular time of your life; wander at your free will all over your life: talk only about the things that interest you for the moment.' Twain even invited his recently appointed biographer, Albert Bigelow Paine, to

sit in while he dictated a half-million words in 250 or so sessions between 1906 and 1909. Twain was convinced that he had stumbled onto something original: âI intend that this autobiography shall become a model for all future autobiographies when it is published, after my death, and I also intend that it shall be read and admired a good many centuries because of its form and method.'

What he dictated wasn't all that revealing or even necessarily true. Paine, who was familiar with the basic facts of his subject's life, saw soon enough that âMark Twain's memory had become capricious and his vivid imagination did not always supply his story with details of crystal accuracy. But it was always a delightful story.' The experiment was a financial, though not critical, success: in 1906 Twain began selling five-thousand-word autobiographical instalments to

The North American Review

, a venture so profitable that he was able to purchase the 248-acre Redding estate and build a villa that he had initially considered naming âAutobiography House' before settling on âStormfield'. He was confident that he could churn out fifty thousand words a month of autobiographical dictation for the rest of his life.