Counternarratives

Authors: John Keene

For Rudolph P. Byrd

and Gerard Fergerson

and in tribute and thanks

to Samuel R. Delany

CONTENTS

On Brazil, or Dénouement: The

Londônias-Figueiras

An Outtake from the

Ideological Origins of the American Revolution

A Letter on the Trials of the

Counterreformation in New Lisbon

I

COUNTER

NARRATIVES

Perhaps, then, after all, we have no idea

of what history is: or are in flight

from the demon we have summoned.

James Baldwin

The social situation of philosophy is slavery.

Fred Moten

So it is better to speak

remembering

we were never meant to survive.

Audre Lorde

MANNAHATTA

T

h

e canoe scudded to a stop at the steep, rocky shore.

There was no slip, so he tossed the rope, which he had knotted to a crossbar and

weighted with a pierced plumb square just larger than his fist, forward into the

foliage. Carefully he clambered toward the spray of greenery, the fingers of the

thicket and its underbrush clasping the soles of his boots, his stockinged calves,

his ample linen breeches. A thousand birds proclaimed his ascent up the incline; the

bushes shuddered with the alarm of creatures stirred from their lees; insects rose

in a screen before his eyes, vanishing. When he had secured the boat and settled

onto a sloping meadow, he sat, to wet his throat with water from his winesack, and

orient himself, and rest. Only then did he look back.

The ship, the

Jonge Tobias,

which had borne him and the others

across more nautical miles than he had thought to tally, was no longer visible, its

brown hulk hidden by the river's curve and the outcropping topped by fortresses of

trees. The water, fluttering like a silk shroud, now white, now silver, now azure,

ferried his eyes all the way over itself eastâhe knew from the captain's compass and

his own canny sense of space, innate since he could first recallâto the banks of a

vaster, still not fully charted island, its outlines an ocher shimmer in the morning

light, etching themselves on his memory like auguries. Closer, at the base of the

hill, fish and eels drew quick seams along the river's nervous surface. From

hideouts in the rushes frogs serenaded. Once, in Santo Domingo where he had been

born and spent half his youth before working on ships to purchase his freedom, he

peered into a furnace where a man who could have been his brother was turning a bell

of glass, and he had felt the blaze's gaping mouth, the sear of its tongue nearly

devouring him as the blown bowl miraculously fulfilled its shape. Now the sun, as if

the forebear of that transformative fire, burned its presence into the sky's blue

banner, its hot rays falling everywhere, gilding the landscape around him. He was

used to days and nights in the tropics, but nevertheless crawled beneath the shade

of a sweet gum bower. He turned down the wide brim of his hat, shifted his sack to

his left side, near the tree's gray base, opened his collar to cool himself, and

waited.

The first time he had done this, at another, more southerly landing

nearer the dock and the main trading post, one of the people who had long lived here

had revealed himself, emerging from an invisible door in a row of bayberries,

speakingâyes, repeatingâa soft but welcoming melody. Jan, as Captain Mossel and the

crew on the ship called him, or Juan, as he was known in Santo Domingo, or João as

he had once been called by his Lusitanian sailor father and those like him among

whom he worked, the kingdoms of the Iberians being the same in those days, and

before that Mââ, the name his mother had summoned forth from her people and sworn

him never to reveal to another soul, not so distant, it struck him, from the

Makadewa

as the envoy of the first people had begun to call himâhad

stilled his ear like a tuning fork until he captured it, and with the key of

this language that most of the Dutch on the ship assured him they could not fully

hear, he had himself unlocked a door. Pelts for hatchets, axes, knives, guns, more

efficient than flints or polished clubs in felling a cougar, a sycamore, an enemy.

He had wrung a peahen's neck and roasted an entire hog, but despite having heard

several times the call to revolt, he had never revealed a single secret or

shibboleth, nor had he killed or been party to killing another man. So long as the

circumstances made it possible to avoid doing either, he would. Someday, perhaps

soon, he knew, his fate might change, unless he overturned it.

The envoy had, through gestures, his stories, later meals and the voices

that spoke through fire and smoke, opened a portal onto his world. Jan knew for his

own sake, his survival, he must remember it, enter it. He had already begun to

answer to the wind, the streams, the bluffs. As he now sat in the grass, observing

the light playing through the canopies, the shadows sliding across themselves along

the sedge in distinct shades, all still darker than his own dark hands, cheeks, a

mantis trudging along the half-bridge of a gerardia stalk, he could see another

window inside that earlier one, beckoning. He would study it as he had been studying

each tree, each bush, each bank of flowers here and wherever on this island he had

set foot. He would understand that window, climb through it.

He stood and unsheathed his knife. Then he removed a roll of twine from

his bag. Using the tools, he marked several nearby spots, hatching the tree and

tightly knotting several lengths of string about the branches, creating signs, in

the shape of lozenges, squares, half-circles, that would be visible right up to

sunset. In nearby branches he created several more. There was always the possibility

that one of the first people, whom he expected to appear at any moment,

though none did, or some nonhuman creature, or a spirit in any form, would untie the

markers, erase the hatchings, thereby erasing this spot's specificity, for him,

returning it to the anonymity that every step here, as on every ship he had sailed

on, every word he had never before spoken, every face he had never seen until he

did, once held. If that were to be the case, so be it. Yet he vowed not to forget

this little patch where a new recognition had dawned in him. If he had to commit

every scent, every sound, even the blades of grass to memory, he would. He walked

around, bending down, looking at a squirrel that had been looking intently at him. .

. .

Despite having no timepiece, he knew it was time to return. A breeze, as

if seconding this impulse, sighed

Rodrigues

. He began sifting through his

store of images for a story to recount to them, shielding this place and its

particularities from their imaginations. He broke off two branches big enough to

serve as stakes and carried them with him down to the bank and the canoe. Using his

knife and fingers, and, once he had created an opening, the thinner end of his

paddle, he dug a hole, and pounded the first stake into it. Using the twine he

created a cross with the other branch, then strung a series of knots around it, from

the base to the top, wishing he had brought beads or pieces of colored cloth, or

anything that would snare the gaze from a distance. He stepped back to inspect it.

He was not sure he would be able to spy it from the water, though it commanded the

eye from where he stood. But, he reminded himself, once he returned to the ship, it

would be for the last time, and he would have months, years even, to find and

reconstruct this cross again, to place a new one. The first people would guide him

to it, too, if they happened upon it. He replaced his knife and the twine, collected

his anchor, then hoisted himself back into the canoe, paddle in one hand, in the

other his ballast. He pushed off from the shore, out into the river, and as he

glanced at the cross, it appeared to flare, momentarily, before it disappeared like

everything else around it into the island's dense verdant hide. It was, despite his

observations of the area, the one thing that he recalled so clearly he could have

described it down to the grain of the wood when he slid into his hammock that night,

and, when he returned a week later, his canoe and a skiff laden with ampler sacks,

of flints, candles, seeds, a musket, his sword, a small tarp to protect him from the

rain, enough hatchets and knives to ensure his work as trader, and translator, never

to return to the

Jonge Tobias,

or any other ship, nor to the narrow alleys

of Amsterdam or his native Hispaniola, the very first thing he saw.

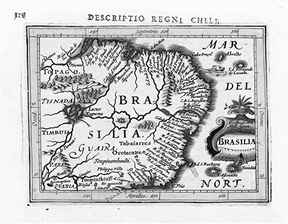

ON BRAZIL, OR DÃNOUEMENT:

THE

LONDÃNIAS-FIGUEIRAS

On Brazil

STAFF REPORT

The nude, headless body of a male was discovered shortly

after dawn in an alley off Rua dos Cães, at the edge of the new and unauthorized

favela of N., on the periphery of the industrial suburb of Diadema, by an

officer from the São Paulo Metropolitan Police department. The department and

the São Paulo State Police have opened a joint investigation. . . .

According to Chief Detective S.A. Brito Viana,

authorities still have not confirmed widespread rumors that identification

found on the body indicates the deceased is banking heir Sergio Inocêncio Maluuf

Figueiras, 27, who has been listed as missing since the early summer. . . .

On Brazil

F

rom the 1610s, the

Londônias were the proprietors of an expanding sugar

engenho

in the

northeasternmost corner of the captaincy of Sergipe D'El-Rei. The plantation

began some meters inland from the southern sandy banks of the Rio São Francisco

and fanned out verdantly for many hectares.

The first Londônia in New Lisbon, José Simeão, had arrived in the Royal

Captaincy of Bahia in the last quarter of the previous century after receiving a

judgment of homicide in the continental courts. Before this personal calamity, he

had spent several decades serving as a sutler to the King's army. Because his first

wife had died during childbirth while he was posted in Galicia, once he arrived in

the land of the

pau brasil

, he promptly remarried. His new wife, an

adolescent named Maria Amada, came from the interior of Portugal's abundantly

expanding territories, and was a productâaccording to Arturo Figueiras Pereira

Goldensztajn's introduction to the

Crônicas da Familia

Figueiras-Londônia-Figueiras

âof one of the earliest New World experiments:

the coupling of the European and the Indian. José Simeão and his wife settled in the

administrative capital, São Salvador; he worked as a victualler and part-time

tailor, drawing upon skills acquired in his youth, and she produced several

children, only one of whomâFrancisco, who was known as “Inocêncio” because of his

marked simplicity of expressionâlived to adulthood.

Francisco Inocêncio followed his father's path into the military.

Instead of provisioning, he became an infantryman. By the time he was 25, he had

taken part in several campaigns against Indians, infidels, foreigners, and

seditionists in the western and southern regions of the King's territories. His

outward placidity translated, in the midst of battle, into a steadfastness that even

his opponents quickly came to admire. Facing arrows or shot, he neither faltered nor

flinched; when his flatboat capsized, he calmly surfaced on the riverbank, pike in

hand. A commission and promotions were soon won. But there is only so much gore that

sanity can bear. He eventually resigned to settle in the remote northernmost region

of São Cristovão, Sergipe D'El-Rei, near the Captaincy of Pernambuco, where he set

up a small estate. Not long thereafter he married the widow of a local

apothecary.

Though his wife was not beyond her childbearing years, Francisco

Inocêncio adopted her son, José, who was thenceforth known as José Inocêncio, and

her daughter, Clara. From his mother, they say, José Inocêncio inherited a will of

lead and a satin tongue. These gifts led to his greatest achievement, which was to

ally himself with and then marry into the prominent and clannish Figueiras family,

which had acquired deeds of property not only in the capital city but throughout the

sugar-growing interior. The Figueirases were also involved in trade, as agents of

the crown, in sugar and indigo processing, and in the nascent banking system. As a

result, they were rumored to be

conversos

. In any case, the royal court

benefited greatly from their ingenuity, as did the colonial ruling class, of which

Londônia soon became a member. To the connected and ruthless flow the spoils.

Within a decade, José Inocêncio had quadrupled the acreage of his

father's estate, acquiring in the process several defaulted or failed plantations,

some, according to his rivals, by shrewd or otherwise extralegal maneuvers. He had

plunged into this business with the same zeal with which his father had once

defended the crown, which is to say, relentlessly.

José Inocêncio was entering the sugar trade as ships were

disgorging wave upon wave of Africans onto the colony's shores, and he viewed this

as a rising historical and economic trend, the product of the natural order. The

mortality rate for slaves was extraordinarily high in 17th-century Brazil. It was

higher still on Londônia's plantation. He could not abide indolence or anything less

than an adamantine endurance, so he devised a work schedule to ensure his manpower

was engaged productively at every moment of daylight. Nightfall barely served as a

respite. Those who did not fall dead fled. He was thought of by his fellow planters

as “innovative,” “decisive,” “driven,” a man of action whose deeds matched his few

words; in the face of such immediacy and success who needs a philosophy or

faith?

On the estate itself, things were moving in the opposite direction. The

final straw came when he ordered Kimunda, a frail cane cutter who had collapsed from

hemorrhages while on his way to the most distant field, tied to an ass and dragged

until he regained consciousness. As stated in the schedule, which each slave was

supposed to have memorized, Kimunda was expected to work his section of the field

from sun-up to midday, circumstances be damned. The result was that a cabal from the

Zoogoo region mounted an insurrection, seizing swords and knives and attempting to

lay their hands on gunpowder. José Inocêncio quelled it with singular severity.

Sometimes the fact of the lesson is more important than what is actually learned.

Half a dozen of the plotters, including Cesarão, a particularly defiant African who

had become the

de facto

leader of the coup, after torching a field of cane

and a dry dock, escaped across the river into the wilds of what is now the Brazilian

state of Alagoas.

José Inocêncio swiftly rebuilt his operation. He viewed himself as a man

of estimable greatness, of destiny. It is undeniable that he had possessed what

might be classed as an exemplary case of proto-capitalist consciousness, for

afterwards he sought out as diverse and well-seasoned a workforce as possible.

Growing markets have no margin for mercy. Several years before his death, he

received a litany of honors from the crown.

The Londônias-Figueiras

T

h

e Londônia family: Londônia's eldest son José

Ezéquiel strongly resembles his mother in appearance, his father in canniness

and business acumen. Short, heavy-set, with a broad jawline covered by a thick,

black, immaculately groomed beard, like most of the Figueiras clan. He is

described in some tendentious contemporary accounts, according to Figueiras

Pereira Goldensztajn, as almost “rabbinical” in mien. Eventually he inherits his

father's estates, and his branch of the family gradually expands them along with

his mortgage empire until the collapse of the sugar economy, despite which these

Londônias head a new feudal hierarchy in the region for generations.

Londônia's youngest son Gustavoâemerald eyes, skin white as moonstone, a

swan's neck, impressive height: all recessive traits, all valued highly by the Court

society in Lisbon. Fluent in gestures, languages, charms. A career in royal law is

predicted for him. By the age of twenty-four, he has infected several women in his

social set before dying of the same blood-borne illness himself.

Maria Piedade, the only Londônia daughter, finding no adequate suitors,

married back into another branch of the Figueiras family.

Th

e other children, as was common even among the rich in those days,

died before reaching adolescence, except for the middle son, Lázaro Inocêncio, who

possessed his father's tendency towards resolute action, his high self-regard, his

inflexibility.

Lázaro Inocêncio

A

fter two

years at the Jesuit college in Salvador, where his classmates alternately

nicknamed him “the Colonel” because of his assurance and hair-trigger temper,

and “Guiné” as a result of his thick, expressive features, swift tan, and

woollen locks, he chose a career that placed him near a center of power. He was

by birth a Figueiras, nothing less was expected. He gained a commission in the

King's forces, serving as vice-commander of a regiment based in Itaparica.

During the final Portuguese invasion to recapture the capital city of Salvador,

in 1625, he held steadfast against repeated charges. After the commanding

officer had taken shot to the chest, Lázaro led his men in a daring advance

through the rump of the lower city that resulted in the capture of a small

batallion.

Despite the fact that his captives were all found mortally wounded, as

soon as the Dutch retreated he was duly commended and promoted. His sense of

superiority and bellicosity, however, caused problems in the context of the general

state of peace. Continued battles with his superiors led him to abruptly resign his

commission. A star does not orbit its moons. He returned to Salvador, and in a

moment of even greater rashness, married the sickly daughter of an immigrant

physician. He found the situation of his marriage and his estrangement from the army

intolerable, and headed south, his goal the distant coastal city of Paranaguá,

essentially abandoning his ill wife, who was, unknown to him, with child.

Fortunately for heroes fate's hand is surest. In 1630 a fleet led by the

Dutchman Corneliszoon Loncq seized Pernambuco. Londônia, who had gotten no further

than the town of Vila Velha, north of Rio de Janeiro, was located and recalled. His

commission involved his resuming leadership of the remnants of his former

regimentâSouza, Antunes, de Mello, Madeiraâwhich was now under the general command

of Fonte da Ré. The Portuguese forces were intent on retaining their patrimony, so

adequate plans were being drawn up. Lázaro Inocêncio, however, pressed to

participate in the first battles in Olinda. A farsighted man, Fonte da Ré recognized

the looming catastrophe and ignored Londônia's agitation to take the field.

But Londônia did have a reputation for bravery, so Fonte da Ré, after

receiving word that an official fleet was already bound toward the seized northern

capital, ordered his commander to head west, up the Rio São Francisco, moving in a

pincer movement into the rear flank of Pernambuco. He was to press into the leaner,

bottom portion of that colony, then head back southeastwards, tracking the southern

rim of the unforgiving sertão, then moving north again towards Olinda, which was

under Dutch control. Rivercraft awaited him on the Sergipe d'El Rei side, provisions

at the post west of the thriving town of Penedo in Pernambuco. He was not to attack

any Portuguese colonials unless they declared allegiance to Nassau. In order to

preserve manpower, he was not to engage in any other combat unless absolutely

necessary. This course of action would keep him out of the main campaign, Fonte da

Ré hoped, until Londônia's enthusiasm could be put to direct use in a clean-up

operation. Two other batallions were added to his command.

After a journey by horse along the coastline to the mouth of the São

Francisco, Londônia and his men set off on pettiaugers up the deep and refractory

river. On the northern shores, past the sandy banks and the falls, settlements and

plantations periodically appeared. The aroma of cane and the sight, from his boat,

of

engenhos

and mills, goaded him like a spur. There was no genius

comparable to that of his people; the greedy Dutch must pay. Within a day he and his

men had passed Penedo and reached a small Portuguese outpost from which they would

proceed into the interior.

As they moved inland on foot, Londônia's men realized he was as

unfamiliar as they with the difficult, nearly impassably dense forest terrain.

Unlike them, however, he was indefatigable. He wanted to drive forward, forward. A

few of his men, however, began to fall by the wayside, to fevers and periodic

attacks by Indians, who had been living somewhat undisturbed in the vicinity.

Londônia demanded that his soldiers not flag: here we see history repeating itself,

though in a guise bearing professional validation. One mutineer he shot outright,

another he threatened with similar summary judgment. On they proceeded, through

forest to clearings of scrub-land and then to forest again: soon, hunger, thirst and

questions about the validity of the mission enjoined the men. Though they marched, there were no Dutch to be found anywhere.