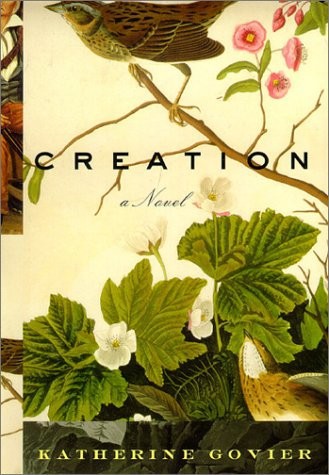

Creation

Authors: Katherine Govier

Tags: #Fiction, #Historical, #FIC000000, #FIC019000, #FIC014000, #FIC041000

This edition first published in the United States in 2003 by

The Overlook Press, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc.

New York

for individual orders, bulk and special sales, contact

salesoverlookny.com

N

EW

Y

ORK

:

141 Wooster Street

New York, NY 10012

Copyright © 2002 Katherine Govier

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

ISBN 9781468303933

For R., E., and N.

CONTENTS

Copyright

Goodbye to Land

Flight

A Name

The Gulf

The Surveyor

The Hold

Obstinate Creatures

Fogbound

The Killing

Dominion

Song

At Last the Wind

Baffled

Desire

The Country So Wild and Grand

America My Country

Fame

The Laughing Song

Colour

Fugitives

Labyrinth

Voluptuary

Lost

Hope

The Strait

Captive

Wild

Background

Counting

The Human Fascination with Birds

Accidental

Epilogue

Illustration Credits

Acknowledgements

Praise for Creation

J

ust suppose.

That it is a bright, cold May morning in the year 1833, and two men alight from the stagecoach in a little town on the Maine seacoast.

They are father and son, judging by their flowing chestnut locks and aquiline features, by their matching one-handed swoop off the high step. The older man slings his gun over the shoulder of his fringed jacket; he must be a frontiersman, a hunter. But he has a certain vibrancy, as if his whole body were a violin freshly strung, and his deep, gentle eyes take everything in. The son, of more solid flesh, has a fine-looking pointer at his heels.

They send their luggage on and climb to a vantage point on the granite rocks of Eastport. There is birdsong: the Cardinal’s whistle, the low warble of the Snow Bunting, the trill of the Pine Warbler. Side by side they look over Passamaquoddy Bay. Chunks of ice still float in the harbour among the muffin-shaped islands. They seem to listen to the air, to the wind; they scan the hills with eagle eyes, as if they might coax the spirits of the place out of hiding. At last, the father gestures below. They set off walking toward the harbour.

The schooner

Ripley

out of Baltimore is not there, but it will arrive any day, says the dray man they accost on the wharf. A certain gentleman has hired it for the season. He plans to sail west and north, around the tip of Nova Scotia, through the Cape of Canso and up into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and from there up the wild north shore of Labrador where only the fishing boats go. He is a famous gentleman. That is to say the dray man himself has not

heard of him, but the newspapers write about him.

What do they say, these newspapers? asks the older man.

Ah, they say that he is a great American and that we ought to be proud. He is a painter of birds. He is making a giant book that will have in it every bird in our land.

But that gentleman is me! exclaims the newcomer, and the three slap their knees and laugh.

THE TRAVELLERS HAVE

come a month ahead of time. There is so much to do. The schooner, when it arrives, must be fitted with a wooden floor in the hold and a table nailed down for the artist to do his work. They find the captain.

Emery — spry, greying, moustached — invites them into his clapboard house at the edge of town. From the parlour he can look over the harbour. With the brass spyglass that sits on the mantle, he scans the port. He has been on the seas most of his life and was once captured by Spanish pirates off Puerto Rico. He eats tobacco as another man might eat a handful of nuts. He will hire the crew. There is a pilot from Newfoundland he knows, and a local boy, Coolidge, good on the water.

In the market, father and son and the three young gentlemen who have joined them from Boston buy oilskin jackets and trousers and white woollen toques with an oilskin awning that hangs down the back to keep the rain from sliding down their necks. They cavort in their outfits and flirt with the ladies who sell knitted goods. By the time a week has passed, they have charmed nearly everyone in town.

The gentlemen roar with laughter over their dinners in the public house. The artist has forsworn grog and snuff, but it does nothing to diminish his fun. He pulls out his flute and plays an air; his son plays fiddle, and the young gentlemen all sing and pull the bar-maids from behind the counter to waltz around the room. Sometimes the artist takes out a piece of paper from his waistcoat and scribbles figures:

victualled for five months, $350 each month

. He checks his multiplication. He writes,

potatoes, rice, beans, beef, pork, butter, cheese

. Other times he falls silent and gazes, abstracted, at a

wall. He goes to the harbour, under the moonlight, and looks to see if the ice is all gone.

His name — the name the world knows, two centuries later — is John James Audubon. He is here, with his great hopes and his desires and his premonitions of doom, preparing for his mid-life voyage. He is halfway through his masterpiece: a catalogue of every bird in North America, represented the same size as in life, and observed by him in nature. It has taken seven years thus far, and will take him six more to finish. He has done this without patrons, selling subscriptions to the book himself, collecting the dues, finding birds in the wild and sending his paintings across the sea to London to be engraved and printed, and then hand-painted.

The great man is as generous with his words as he is with his colours. He tells his stories in many places and in many different ways. He will leave, aside from his great book of pictures and the volumes of words that accompany it, his journals, and many letters.

In fact, in a life so well documented, these next few months form a rare gap. It is as if the dark cloud and fog he sails into transcends mere weather and becomes a state of mind. As if Labrador itself (or its weather) swallows the story. Strange.

Is it because he goes north and off the map?

Because he leaves the sacred ground of his own country and journeys to the least known part of the little-known continent?

Or is it because something happened there, an adventure so grisly the artist had no words to describe it? That he wrote about it and afterwards had second thoughts and destroyed his words?

Or — here we get to the nub of it — is there another reason, a reason to do with his human attachments? Those he loves and especially those who love him. With desire, possession, betrayal, the women and the children he leaves on shore? A reason rising out of old passions or new intimations? Has what happened on this voyage been ripped from the record because someone did not want history to know?

We do know, sitting as we do in their future, that the great man’s son, young Johnny, the one so quick to learn the masts and ropes from the Yankee sailors, will have a wife a few years hence and that

this wife will have a child. And that eventually, when the artist and his wife, and all their children are dead, this granddaughter, Maria, will come into possession of his letters and diaries. She will appoint herself keeper of secrets and protector of reputations. And what she reads about her famous grandfather’s life, and particularly this summer of 1833, will displease her. She will excise huge portions of the journals. She will publish the bowdlerized version and destroy the original. Letters will be lost, burned, turned into dust.

Hence this hole, this gap.

A gap is an opening, a window, an opportunity.

JUST SUPPOSE WE CAN STEP IN.

Let that gap become our present. Knowing future and past, we can live there suspended, masters in our little world of the now. The moment is our only dwelling and we create it with our own understanding. Audubon is a man but more than a man; he is a character, and as a character he becomes a vessel to fill with our imagination. This is, after all, how we understand the world, by investing ourselves in a creature moving through it. It is how he understands birds as well, with that intense subjectivity and identification that endures in his work.

Facts are deceiving. We may know them, but never all of them. Only the bits and pieces that survive the voyage. In real life, the story is never finished. Discoveries may be made to shed light on it; for instance, in some attic, some cellar, the lost pages of the diary may be discovered — Maria may have repented of her decision to destroy them.

Fiction is another story. We can be sure of it, for we make it up; it is complete and finished. We can embrace it, because it is what we know.

EVERY DAY THERE ARE

letters in the mail at the hotel. It is by letter that he keeps himself tied to the world. Lucy admonishes him: “Do not sit in wet clothes. Watch out for Johnny. You know he is too wild.”

The day before departure, he writes back to everyone.

“There are no post offices in the wilderness before me,” he writes

Havell, his engraver in London. He writes to his older son, Victor, also in London, that in his absence, Victor must be vigilant to see that work continues, and subscriptions come in.

He writes to Lucy: “dearest best beloved Friend my own love and true consoler in every adversity. … the most agonizing day I ever felt —”

NOW IT IS THE VERY DAY:

June 6. A festive atmosphere has taken hold of the town. The tailor, the publican and the knitting women, in fact most of the population of Eastport, have downed tools and filtered to the docks to see off the schooner and its crew. The Stars and Stripes are snapping in the wind. Girls in freshly ironed frocks present little baskets of warm bread, and their brothers run up and down the rocky incline of the shore in excitement. The battery of the garrison fires four reports. The cannon on the revenue cutter salutes. The shots echo from the cliffs.

On deck and holding the mast, John James Audubon lets the wind run through his hair. He has such hopes for this journey; will they be fulfilled? The birds — will they show themselves to him? He hopes to find new species, big ones to fill his pages, thirty inches wide by forty inches tall. Such ideas he has: winged creatures, huge and splendidly feathered. It will be a royal court of birds there; it will be the nursery of the entire world of water birds.

The anchor is shipped. The sails are set. The schooner moves gently out of the harbour. The boats that have rowed out to it turn back to the shore. The crowds on the wharf cheer. Then, all but the most loyal turn their backs, roll up their pennants and go about their business.

But not us. We can go with him to sea.

AND JUST SUPPOSE THAT ANOTHER MAN,

in another port, is saying goodbye to land. Captain Henry Wolsey Bayfield is not famous, although as the highest ranking naval officer at the Quebec garrison, he is respected by all the British officers and French

noblesse

. He dines at the

table d’hôte

in the finest hotels, where the officer on his left may have a tattoo on his neck from his time living

in Tahiti with the mutineers of the

Bounty

, and the lady on his right may be an opera singer from New York. He is such a favourite of the governor general’s wife that he has to limit his acceptances to two a week because the parties interfere with his work.

Still, there is no one to bid farewell.