Creation (4 page)

Authors: Katherine Govier

Tags: #Fiction, #Historical, #FIC000000, #FIC019000, #FIC014000, #FIC041000

There is a silence as both men look out to sea. Anonyme pecks restlessly at the fold of skin between Audubon’s thumb and forefinger.

“If you look long enough into the water,” says Godwin suddenly, “you can see there’s light down there.”

“Not here. There’s rocks. Maybe over a sand bottom you’d see light.”

“Aye, here too.”

“I doubt it. Where would the light come from?”

“Comes from below.”

“And what gives off this light, pray tell?”

Godwin scowls, wary of being patronized. “Why, the living things that’s there, I suppose.”

The idea strikes a chord. Audubon has a private theory that the down on herons’ bodies actually glows, allowing the birds to catch their prey in the dark. He has visions of night marshes illumined by the phosphorescent tails of herons. It is one of many scientific notions he has not had time to explore. Why shouldn’t life at the bottom of the sea be like the life in the air itself, producing light?

He does not confide this to Godwin. “Do you know the eastern seaboard?” he asks.

“Clear down to New Orleans. I worked there once.”

“I might have met you, then, when I embarked on the

Delos

for England?”

“Not in the port. I was a bodyguard then, for a man named Nolte.”

“Vincent Nolte? The cotton merchant?”

“Is there any other? Cotton, to start. Then it was sugar, and then it was arms,” says Godwin. “Used muskets. Bought them from the Prussians where they’d left them lying in the fields when they retreated in 1813. Sold them back to the French in ’29, to fight off their own people. Most of ’em were useless. Some rough visitors he had.”

Audubon steps away from Godwin, in the dark. It is bizarre that this pilot should bring up the name of Vincent Nolte. It strains even his credulity, he whose life has been shaped by chance encounters.

Of course it happens. This is the way life works in his adopted, his adored, country. People know people. Vincent Nolte more than most. He made a great fortune and lost it, and the last Audubon heard of him, he was on his way to making another.

There may be few roads in America but there is a skein of names connecting men to men. The high rub shoulders with the low. The famous make their way through crowds and wilderness alike, to fetch up at humble homesteads. Only this year Daniel Webster brought him a brace of ducks to be painted. He and Lucy encountered the great General Clark, who with Meriweather Lewis were the

first Americans to make the crossing west to the Pacific, resting in his wheelchair on his sister’s estate near Louisville. George Keats, brother of the poet John, came to Kentucky with money to invest — but Audubon does not like to think of it: Keats is another man whose debt he is in. Why, Lucy herself has links to the English intelligentsia; her family doctor in England was Erasmus, the grandfather of Charles Darwin the scientist. Everyone of significance has connections, and some people of no significance have them, and some, like himself, invent them.

He tells himself there should be no difficulty tonight, on shipboard, in an old acquaintance conjured. Yet he feels cornered and it seems as if the cold sinks deeper into his spine.

“We’re a long way north of New Orleans. I do not know this Gulf. But you do, then.”

“Aye. The Gulf, the Grand Banks, and all the way down north to the Labrador.”

“Down north?”

“Down north. Up south. It’s how we say it here. They say it’s on account of the maps the Portugee had when they first come for the cod. They say north down’s the way the ancients drew their maps. Or maybe not. Maybe it was just upside down.”

Godwin moves away and is gone into darkness.

This is not inspiring Audubon’s confidence.

T

HE MOONLIGHT DISAPPEARS

and the night goes on and on, black and blacker. The singing is over. The sea briefly gives back a star’s beam, and slops against the sides of the schooner. The mast creaks. The damp salt smell rises into his nostrils. It is quiet.

The bird’s eye is open. Audubon’s eyes are shut. He puts his thumb under the bird’s neck and his forefinger on its crown, and strokes its feathers. It responds by cawing and jumping off his hand. Gone.

“Goodnight, Anonyme,” he says.

He wants to sleep. But first he must speak to Lucy. He speaks to her each night before bed. He has done this in Edinburgh and Liverpool, in the Florida Everglades, wherever he has travelled. He will

do it in Labrador as well. He speaks aloud as is his habit, and only the raven and the tar on the nightwatch hear.

“Lucy,” he says. “My dearest friend and one true companion, my heart’s solace, it is cold and I am afraid. Were I a bird I could escape this place and come to you. Instead I stretch my arms to reach you in the dark. But no. The

Ripley

is hundreds of miles from you, from anywhere. And I must tell you a strange thing: our pilot was a bodyguard for Nolte —”

The ship turns at her anchor. The stars reel in and out of cloud. The rocks, when struck by a bit of moonlight, glistern. There is a scuffle down below as the young gentlemen tumble into their hammocks. The mast creaks, and the ropes rub against the timbers. He will sleep on deck.

“Anonyme?”

A caw from a coil of ropes gives his whereabouts. Audubon gets to his feet, wrapped in his buffalo robe, and looks from shore to islands and back. Earth here looks as treacherous as water. When they want to go on shore, how will they walk?

Will he die here?

No. He cannot.

If he dies, would the Work then be completed by his helpers, his family — his rivals, even? No, he must finish.

On the northern horizon, he notices a great swipe of shimmering pale green, a curtain that seems almost to hum.

Is it some enormous migration of birds? He hugs the robe around his shoulders. Dear God, is it the future, written in wings? Can he read it? It is not so strange a thing, to read the future in what your eyes take in.

H

E CAME TO LABRADOR ALMOST YOUNG

. He will leave almost old.

He arrived here quite sane. When he leaves, madness will have taken root. He will live another decade and a half, at the end of which he will sit slack-jawed in his chair, a great man but still a poor man, and he will not know his own son.

He came here a hunter and a singer of birds and he will leave here a mourner of birds.

He came to Labrador an honest husband who loves his wife and two sons, though not above all, and he will leave — but this part is unknown. A blank. A darkness. The shining green curtain, as astonishing as the landscape out of which it sprang, is gone.

H

e wakes on the deck well before dawn, at three a.m. Usually he is ready for breakfast but today he awakes with a sense of injury;

mal de mer

has seized him although the sea is quiet. The air temperature is forty-three degrees.

He drags himself down to his berth and calls the captain. He reminds himself that Emery is a Yankee; Audubon believes the Yankees to be fine sailors.

“It was a tragedy we could not land on the Bird Rocks,” Audubon begins.

Emery has already quelled the fears of the crew about the weather, which is even more foul than normal in these parts. His square face shows not a flicker of emotion yet one knows him to be benign. His moustache is stained coppery from tobacco. His eyes meet the artist’s for a few seconds and then he says, “You had the next best thing, your son.”

Audubon is not mollified. “Godwin puts caution above finding birds.”

“In matters of safety, I will bow to his experience,” says Emery. “You won’t find birds if we’re wrecked.”

“No! But you must understand. The birds are the reason we’ve come. And I must find them before my rivals do.”

“I fully understand, sir,” Emery says gamely. “Obsession drives many a sea voyage.” Were it not for the moustache, you would see a wry twist to his mouth.

Audubon is not amused by this perspective, and Emery continues.

“The seriousness of your mission was much impressed on me. It

isn’t for every sailing of the

Ripley

that the whole town turns out with a gun salute to send us off!”

Audubon, although feeling ill, grasps Emery’s wrist, “My competitors have seen my

Birds of America

and they are rushing into print with imitations. One John Gould, for example, who has an excellent lithographer as a wife. But Gould stays at home and draws the birds from specimens. There are others — Edward Lear … but I am the only one who observes the birds in the wild.”

Audubon lets his grip relax as he twists with his nausea.

Gently, Emery withdraws his hand. “There was one man. An Alexander Wilson. We have his book in our home.”

“Wilson? He’s been dead twenty years. I met him once, entirely by chance.”

Wilson had come into the store Audubon owned for a time in Louisville, Kentucky, and tried to sell him a subscription to his book. He was a wizened, long-faced man with a sad look, the look of a peddlar who expected to be beaten back from the door. Audubon stood behind the counter, turning the pages of Wilson’s portfolio. His partner stuck his head over Audubon’s shoulder and said, “Yours are better!”

They spent a day or two together; he helped Wilson find birds. And then — how does the saying go? no good deed goes unpunished. Wilson passed on stories about him to all the important bird people in America. So, many other American ornithologists became Audubon’s implacable enemies. A man named Ord, in particular, had staked his reputation on the wandering Scot. When Audubon began his own work, Ord teamed up with the Englishman Waterton to attempt to destroy his reputation. This is the worm in Andubon’s belly; it has been there for years, and is clearly not to be escaped.

“Wilson did travel, I’ll give him that,” he tells the captain. “But he never went to Labrador.”

T

HE

RIPLEY

MAKES SLOW PROGRESS

through the Gulf. The following day is warmer and still calm. The ship sits at anchor. Audubon works at his table in the hold, rubbing his hands every few minutes to keep them nimble, stamping his feet, straining his eyes to see without

sunlight. The young gentlemen fish for cod, and Johnny catches one that weighs twenty-one pounds. The cook fries it in butter and they dine on it. At six p.m. the wind springs up fair and they at last make sail to the northeast. Audubon sleeps, his sickness passing.

The next morning before dawn the sea is covered with foolish guillemots playing in the spray of the bow, and the air is filled with velvet ducks, thousands of them flying from the northwest to the southeast. The wind continues all day, and at five o’clock Audubon hears the cry of land. They think they see a mass of sails, but discover on closer examination that it is snow on the banks of Labrador. They pass the mouth of a wide river.

“What is that river called?”

“Natashquan,” says Godwin. “It means ‘where the seals land’ in Indian.”

“It looks a good place for birds.”

“We can’t anchor there. That’s the British trading post. No American boats are allowed. We’ll have to go on.” Audubon watches the river retreat behind them.

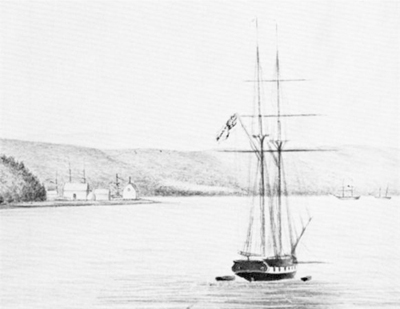

They come to the harbour the Americans use, known as Little Natashquan. As the

Ripley

nears the anchorage, seals rise to the surface, putting their heads and necks up in the air, sniffing it, and them, and then sinking back. From his position on deck, Audubon spots two large boats with canoes lashed to the sides, sailed by Montagnais Indians, all in European dress save for their moccasins.

He hails them to ask about the birds. The men are good looking with clear red skin and they speak French. They say they cross inland every year where there is not a single tree; they have to carry their tent poles. They hunt, though fur animals are scarce. He asks them to bring him grouse.

At last the

Ripley

makes anchor. He cannot wait to go ashore. He jumps into the whaleboat with Johnny and rows. Once landed, he finds a land bewitched, full of pygmy trees and bushes, velvet moss in which he sinks to his knees and not a patch of earth. The moschettoes swarm him as if they had not seen a red-blooded creature for a hundred years. He swats, and bleeds, and swats more until he finds the birds.

At the sight of wild geese, dusky ducks, scoters and red-breasted mergansers, he forgets his discomfort.

He encounters a solitary settler, a French-Canadian, who serves him good coffee in a bowl. The coffee warms his stiff and aching hands, as they sit inside his one-room log cabin.

“This land is a species of Eden,” says the settler, “despite the seven feet of snow that fall in winter.” He has an acre of potatoes planted in sand. The cod are enormous and plentiful, but there are fewer than half the fish there were when he first came here. The European boats are taking them.

“And birds’ nests?”

“Back there,” the settler says, pointing to the marshy bits near the river mouth.

On returning to the schooner, Audubon assails Captain Emery. This journey will cost him thousands of dollars; he has his son and the four young gentlemen to take care of, the provisioning, the hiring of crew. It is an outlay of money which must bring tangible results in the form of birds. “The best nesting grounds are back at the river’s mouth.”

Emery listens with his chin down. “The English keep the Americans out. Further on then, we’ll find our own harbours.”

Audubon stares at the captain. Emery is polite and immovable. By habit the captain’s eyes scan the water. What he sees makes him smile. “Look.”

There is another visitor to the harbour, a schooner that looks like a black man-of-war.

“What is that vessel?”

“We’ve just had a stroke of luck. It’s the Quebec surveying vessel,” says Emery. “If anyone knows these waters, it will be her captain.”