Creation (26 page)

Authors: Katherine Govier

Tags: #Fiction, #Historical, #FIC000000, #FIC019000, #FIC014000, #FIC041000

On July 12, the morning is fine. Bayfield is up at four, observing altitudes with his altazimuth. Collins has not yet come back and Bayfield is concerned. No sooner has the sun got up twenty degrees over the horizon than fresh gales come in from the east. The minute the men get out of their tents they are soaked. But before long Collins returns and they have measurements to put in the books.

On July 13, the weather is at least dry. Collins this time sets off to the St. Mary’s Islands and Bayfield returns to sketch the mainland. Here he spies, grey and soft-cornered and seemingly ready to slide into the granite, a cedar cabin. Approaching it, he sees a man seated on a rock scraping the flesh from a sealskin in the way of the Esquimaux women. This man stands and greets him as if it were normal to encounter a British officer rising from the mist. He is named Joshua Bussière, and is a hunter and seal fisher who trades with the Indians who come by. Bayfield opens his sketchbook to show his approximation of the nearby coast. Bussière extends a finger to indicate what is the mainland and what is island. Even better, he lends Bayfield his dry hut and a table on which to make his notations.

“

The men will be vulnerable in the small boats

.”

Bussière has brought good luck; the next day they have fine weather for only the second day since leaving the

Gulnare

, and manage to cover thirteen miles from Watagheistic Island past the Étamamiou River. The scenery is magnificent; there are falls above the mouth of the river, and a sand beach with long spits running half a mile on either side. Beyond that is a forest of tiny dead, silvered spruce trees preserved like glass ornaments. They camp on a high, barren granite island —

red feldspar with quartz and black mica, no hornblende

, he notes — with a dangerous reef to the south. It has been their best day since leaving the

Gulnare

. But as night falls Bayfield looks apprehensively to the north and east: the view is crammed with rocky islets and sinister, half-sunk rocks.

On Monday, July 15, the wind, the rain, the cold, and the fogs descend again. They have no wood and no protection. Their attempt to cross to the northeast is baffled by the weather. Both boats retreat to a small cove of a smaller island of the group they are in. The men collect driftwood. They make camp but cannot make the wood burn. The rain is falling so heavily that Bayfield can neither write nor calculate without risking an ague from sitting still.

There is nothing to be accomplished. Augustus Bowen, stalwart that he has been, has a deep, sore cough. Bayfield commands him to have the men run races on the rocks to keep from freezing, all but the lame Morgan, who sits nursing his toes. Bowen takes his orders with a smart nod, but, as he stands, chronometer in hand, presiding over the sullen ragtag relays, there is a new distance in his manner. It is as if he were not really here, but only looking in on the adventure.

“If my godfather could see a lieutenant of the Royal Navy thus employed!” he says.

“Would he be amused?” asks Bayfield, who is not. “A little play will distract and lighten us.”

Bowen gives him a look not of the sort one gives a superior officer, but because it is without words, Bayfield decides to ignore it. They have been together for six years and have seen things no man should see; it is a bond. The man is simply not feeling well.

Only Collins gets into the spirit of the races. At length Bayfield allows Bowen to step away, and Collins, stopwatch in hand, soon has the others tied in pairs for three-legged races and, improbably, cheering and laughing.

For the next five days the weather is unspeakable.

Morgan’s foot is swollen red up to the ankle. Bayfield chews stolidly in the mess under canvas with Bowen, who appears to be waiting for him to act. The men refuse to eat breakfast. Even Collins cannot make them pleasant.

“You cannot make a man eat who will not,” he observes. The eggs, coffee and biscuits go to waste. Aided by an ever more saturnine Bowen, Bayfield takes what observations he can. The men watch hungrily for any sign of weakness in him. There are no such signs. At night, under the stars, when the men are in their tents, Bowen speaks.

“The men feel there is no reason to risk their lives. This coast is so bad, they say, no one will ever sail it.”

“That is not for us to judge. We have our task.”

“Of course we do, sir. I merely report what the men are saying.”

July 18 is a useless day sunk in dense fog. Bayfield sits with the measurements he has made, trying to the best of his ability to plot a future course for the

Gulnare

, assuring himself they have not left out any of the rocks in the channel. On July 19 he orders the provisions enumerated; they have enough for nine more days. He sets the men to catching puffins and young gulls and collecting mussels to supplement their rations. Egged on to disobedience by the limping Morgan, they simply refuse to catch anything.

“You cannot make a man hunt who will not,” observes Bowen.

“Indeed you cannot.”

“Perhaps they believe that if they don’t hunt, you will let them return to the

Gulnare

.”

“I shall dispel that notion.”

Bayfield announces to the men that, if they are short, they will go on half rations. He goes out to hunt and by sheer luck finds and shoots three partridge. The men are not too proud to eat them. After dinner he sits in his tent and writes in his journal.

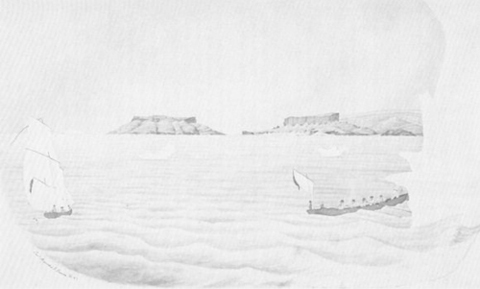

Description of the coast from Petit Mécatina to this camp: labyrinth

.

At one o’clock the next morning Bowen enters Bayfield’s tent to report talk of mutiny.

A

udubon tarries longer in Ouapitagone. He and the young gentlemen return to the inland lake. Fresh blades of grass of a pure pale green have sprung up at its edge; here, summer is only now beginning even though it must end in a few weeks. The Montagnais woman does not reappear. Perhaps she was never there at all. She might have been a spirit, a creature of the wilderness, were it not for the crucifix at her neck. It is a mark of the white man, and to his mind it makes her vulnerable.

The loon is there, her beak like a periscope aimed over the surface of the lake.

He settles himself in the reeds. The loon is a bird he loves to watch. She appears to be alone but is never so. Before long the male speeds into view, his neck curved downward, acknowledging her. Some distance away he glides down to the surface of the lake. Waterborne, but well apart, they call gently back and forth. Then they beat the water with their pinions, dive and rise side by side.

Audubon searches for nests at the water’s edge, and finds several. He observes that, contrary to the assertions of both Wilson and Bonaparte, the loon does not cover its eggs with down, and that not only the female but the male sits on the nest. He sees young birds, downy and new, one day out of the egg. They already swim like fish. The little ones dive under the water, wriggling into the mud. Johnny catches several on the bottom by placing his gun rod in their way.

But the adult birds are not easy to kill. Audubon shoots one on the wing. It falls to the water, but then dives and swims a long way under the surface before bobbing up at last, breast skyward.

The loon is no easier a bird to paint. He sets up a male, nailing its feet to the wooden stand; it has a tendency to fall face forward, its feet being so far backward under its body. He threads wires upward through the cavity of the bird, into the neck and through the breathing passages. He arranges a pair in summer plumage as if they are floating on water by impaling them on several stiff wires that run through their bellies. He draws their long graceful feet and webbed toes fanning beneath them through the water. He gives passing thought to how Havell will manage to replicate this transparency, but is confident that he can.

He sketches a downy fledgling half hidden in grasses, with a pitcher plant to the left. The male’s beak tends to the sky, slightly opened. The back of his head is to the viewer; the bulge of his eyes shows on either side. Are his eyes really that big? Audubon sees them that way. He draws their long webbed feet scale by scale, using, for this task, the quill of a trumpeter swan, which, he has discovered, is sharper and more flexible than any steel nib he could buy. He then returns to the centre of the picture. He creates with delicacy the profile of the female’s sharp, straight, definitive bill, shut tight. But there is great sensuousness in the necks of the pair, which answer each other curve to curve.

He moves on to colour: with blue-black and chalk-white he spends hours dappling the bird’s backs. He uses a fine, soft brush for these teardrop dashes of white. The young bird, in contrast, is mossy brown, shadowed by rock. He paints the respectable grey of the adult heads, the shameless nude beige-white of their breasts. Red eyes. Red throat. Claret for the petals of the pitcher plant.

He remembers, as he uses a shade of red that the gloom of the day hardly allows him to see, the afternoon he spent with Bayfield. He remembers tolling the birds, running at them with handkerchiefs waving, and the birds taking the challenge, running head on to meet them. A game, he called it, but Bayfield was not so sure. He considered the loon a valiant bird, almost British. But in Audubon’s hands the loon becomes a voluptuary.

In the hold of the

Ripley

, dabbing with his red paint, Audubon is maddened to be reminded of Maria again. He could draw the

shape of her now although his fingers are numb. The upright carriage, the small breasts — a girl’s breasts that never suckled a baby. He pictures her neck tilted and inclined lightly over her drawing: she does not tighten over it, as poor students do, but rises to the paper. The shapes rise with her breath and make themselves on the paper. Her lips are shut but lightly so, ready to change at a word of affection or a criticism.

“Why are you drawing that Snowy Owl? Have I asked you to?”

The lower lip drops a fraction of an inch, wobbles a little even while her eyes grow huge and wet and a small flush makes itself visible above the tight lace at her neck.

Perhaps it is Maria’s responsiveness he loves. Certainly it is long past the day when he had such power over Lucy, who no longer blushes or nearly faints with his attentions. Lucy is not tender. She is not beautiful. Or at least, he says, castigating himself, he cannot see beauty in what she is now. It is his fault. But he cannot change this. Would not change it if he could. What is he, if not a lover of beauty? Maria tells him he is an ungrateful child. Maybe so. But ungrateful children are full of passion and passion itself is the stuff of life.

Who is this woman who haunts him from south to north, she who waits in hot Charleston painting butterflies and flowers? A spinster engaged in a spinster’s work, weighing no more than a hundred pounds. A magnet to his eyes; a new enchantment to be discovered every day. Only two weeks after meeting her he wrote Lucy about the Ground Dove: he had drawn five of them on a wild orange branch.

It is one of the sweetest birds I have ever seen

, he told her. He did not tell her that the pastor’s unmarried sister-in-law was at his side, or that he gave Maria a piece of the precious Whatman paper to work on. That she was inspired by his example to paint a Ground Dove herself. Hers had a certain charm but lacked finesse.

But Lucy would know, without him telling her. And what she did not divine, she heard from Bachman, who wrote to Lucy that her husband taught Maria to draw birds. “She now has such a passion for it that whilst I am writing she is drawing a Bittern he put up for her at daylight.”

Bachman has played a curious role in this flirtation. First he offered his sister-in-law to Audubon. “Drawing is an amusement to her, and to gratify you will always afford her pleasure,” he said. He gushed her praises. “My sister Maria is all enthusiasm and I need not say to you that she is one of your warmest admirers. The admiration of such a person is a very high compliment.”

Now he seems to want her back. He has little possessive fits; he acts as if he owns Maria Martin in the same way he owns his wife. Bachman liked to tell the story of the six months he and Maria spent together in upstate New York, years before Audubon met the family. He had fallen ill and could not travel home. Maria nursed him. For weeks he lingered near death. When he could walk she took him to Thornburn’s Establishment for Rare Plants. There, in the greenhouse, the glass bubble, the world within the world, they saw orchids and African grasses, bizarre meat-eating plants, giant roses and shy water lilies.

Maria told the same story, of her sick, diminished brother-in-law and how together they roamed the world in miniature. Only Harriet did not mention it. Audubon is shot through with rage when he thinks of this time. Bachman must have held her arm, he must have leaned on her, so much younger, so tiny but so strong.

But he can do nothing but house this rage, hold himself still when it shakes him. When she painted the Snowy Egret, he allowed himself to become angry with her. Such a relief it was to give in to his temper, to shout and swing his arms, to let his words flay that ivory complexion, to see the lines of scarlet rise in her throat, to flush hot with his own sense of rightness. In response, her flowers became more sumptuous. He used her

Gordonia

for the Fork-tailed Flycatcher. He copied her watercolours of the male and female sylvia onto the sheet of

Franklinia

she painted the previous summer. Then came her incomparable trumpet-creeper.