Creation (39 page)

Authors: Katherine Govier

Tags: #Fiction, #Historical, #FIC000000, #FIC019000, #FIC014000, #FIC041000

T

HEY ARE SINGING

, across the water. He wraps himself in his robe and lies on the deck. In his hand he holds not an egg but a stone, one which Bayfield gave him, a stone without a name, a green stone found on a beach. He thinks he sees a schooner, black, looking like a man-of-war, slide through the tickle where, sails slack, it comes to a standstill and drops anchor.

Captain Bayfield is up the mast in the white billows of moist air. Below him, the chains of the anchor rattle. The sailors pull the heavy iron links, which fall like hammer blows in the muffled air. Then there is a trill of these blows, a long rattling song of them as the anchor plunges through the water to find a hold on bottom.

Audubon hails his friend through the fog. Mast to mast, schooner to schooner, mooring to mooring. Sir! Well met, again! How do you fare?

But the black schooner is not there.

It is the music that undoes him. The stone is warm now from his hand; he presses it against his heart. He turns the mass of it in his palm. It is heavy and smooth, preserved in layers. Some life has been entombed in it. He feels love, strong as grief, like a slow bleed.

He thinks of those he loves.

Lucy, of course. His dearest best beloved.

Johnny, his son, the wild one who must be tamed.

Victor, the elder, the angry one.

The two baby girls, dead.

Maria, a child too, a dangerous child.

Birds.

And who has he forgotten?

The ship rocks on its anchor.

He is Monsieur Newhouse and he is handed off the ship into France, into the arms of a man he knows as his Papa and a woman who says he must call her Maman. He lets the woman lift him up. He goes still as a squirrel. His feet dangle at her knees. His empty little boy heart is all he can offer. He lets his head lean on her bosom. The heart inside his shirt taps away like a little clapper inside a bell.

Maman

, he tries.

He must win her, he knows. She must love him, otherwise they may pack him off again on another ship, with another false name, and some cabin boy following him to make sure he does not fall overboard, and teasing him when he cries. The hideous and endless rocking.

When she puts him down, he takes her hand in his and holds it carefully, like a precious thing, and stands very quietly. At home, she sits with him in the garden and shows him the birds that come for the crumbs, telling him the names of the ones she knows. And when he jumps up to run after the cardinal she stands with one hand over her brow, watching after him. When it seems he will get out of sight she calls — Jean Jacques!

She calls him and he stops and turns back. But there is another call from the depths of the trees. The birds! (Even now he hears them calling, hears the rush and thunder of their wings. The birds, the mysterious birds, whose beauty has filled his days and years. In their shadow he will spend his life’s allotment.) He is looking over his shoulder at her standing there looking after him from under her shading hand, in the sunlight, even as he runs from her, a delighted boy, knowing she will love him and she will wait for him.

T

HE SOUND OF REVELRY

is loud in his ears. Nature will not die before I do, he thinks. I shall complete the Work, I shall be a famous man. My family will rest secure in my fortune and those birds shall have their monument — he thinks of his great Work now as a memorial as much as a discovery — and those who come afterward will be grateful to me. And with that, he falls into a deep sleep in which the songs and the dancing and the laughter play on until long past the dark, and when the dawn comes as usual he rouses himself, goes to the hold and sits at his table to paint as the young gentlemen come in from the ball.

“

I shall complete the Work, I shall be a famous man

.”

T

he past is fantastical. Women in red turbans loiter under painted ceilings amid footmen with white wigs. A hunter in fringe strides over London hills with one hundred pounds of Art on his back. There are, wobbling in little rowboats on the breast of the deep, men in blue serge holding metal arches to the stars. A genial, nagging pastor with a sweetheart sister-in-law, and kitchen slaves named Venus and Adonis. There are double-crested cormorants in bachelor tiers; sounding machines made of chain and lead balls; iron beds set up in the middle of nowhere, with cups and saucers laid out for tea.

Fantastical. But is it imaginary?

Are the birds,

Drawn from Nature by J. J. Audubon

, a fantasy?

Is Bayfield’s coast a fantasy?

Is the fecundity of the past a fantasy? Dolphins that skip across the surface of the water, a barrel of salmon in an afternoon, clouds of curlews descending to strip the berries off the bushes in a matter of minutes, a strait running with cod where the gleaming black backs of whales breach and clip the surface like so many scythes?

Does this exist anywhere outside of our imaginations? Did it ever exist? Codfish thrown on the deck by the thousands, a certain Mr. Jones who had or did not have forty dogs and lived a modest ambition, to be free from lawyers? Phalanxes of foolish guillemot greeting the European boot where it steps on the rock. Velvet moss, so deep you sink to your knees, growing in a teacupful of soil.

Say the names: Natashquan, Kégashka, La Romaine, Mutton Bay, La Tabatière, Petit Mécatina, Gros Mécatina, Bras d’Or, Blanc-Sablon.

Audubon Island. Bayfield Island. The Strait of Belle Isle, a transit to a fabled past. Giant mammals once bored through it, leaping in black arcs to the harpoon. The sky was a torrent of birds. And under it, yes, are the shadows of those adventuring men who, at the time decreed by thirteen carefully watched chronometers, came to this place. Came believing themselves agents of God and of Art.

Two men, two missions, each a vector of his time and ours. Audubon came to record the creatures and left wishing to preserve them. Bayfield tried to make the waters safe in the only part of the world where north is down and south is up, believing that the wilderness in man and in the world might be measured and brought into our ken. But the passage was fraught with peril. Men and weather have evil moods, and the future was beyond any power to chart.

Audubon’s Birds still glitter 170 years later, while the creatures he watched in nature are gone. For it came to pass as Audubon predicted. The fish were drained from the sea and the clouds of birds failed to return and the native people fell prey to despair. The wild habitats were eroded and it was this as much as the destruction of eggs and the indiscriminate shooting that extinguished the wild creatures. As Audubon suspected, man could not be moved to pity the birds. He saw the future and it was terrifying; he saw the wilderness made barren, and then he went out and shot twenty-seven puffins for sport. He saved the birds in art, and that was all he could do.

What are the facts? Godwin, saturnine with his plug of tobacco, steps from the foredeck. Where is the shoreline? We can’t trust these charts. They are inventions. I need to know what is there. I cannot steer the ship and read them too!

H

ERE ARE THE FACTS:

When Audubon reached New York in September 1833 after his return from Labrador, he found that Bachman had got there before him. He had persuaded Lucy that the family should spend the winter in Charleston, where they would all help Audubon with his birds. Audubon was only too happy to comply. He wrote Victor to buy him

a new gun, put Johnny on a ship to Charleston and set out by land with Lucy for the house on Rutledge Avenue, the garden, and Maria, planning to deliver numbers and collect dues along the way.

In Philadelphia he was arrested for his old Kentucky debts, and jailed. Lucy raised bail and they proceeded on their way, stopping in Washington to see the president. In Charleston, Lucy took over Maria’s task of teaching the children French while Bachman, Audubon and their sweetheart worked together in the study. For the next half-year they painted and wrote; Lucy transcribed her husband’s Labrador journals for the letterpress. By July 1834 they were able to ship twenty-five completed paintings to Robert Havell.

During this time John Woodhouse fell in love with Bachman’s seventeen-year-old daughter, another Maria. Victor begged for his father’s presence in London, until reluctantly Audubon sailed with Lucy and John, who was unhappy to be separated from his intended bride.

Maria Martin had waited three years, often in the company of the man she loved, painting with him, laughing and teasing on garden walks, giving him an intimacy that surrendered all and demanded little.

And then she left him, as he had known she would. In doing so, she abandoned Audubon to his wife and his children, in short, to the people who loved him. It was a severe, perhaps fatal, blow to the heart. She was his last young woman, his last rapture, and his last bird. After her fecund sister Harriet died, Maria Martin married her other old man, her brother-in-law John Bachman, the Lutheran pastor. He was righteous and scolding; she had nursed him and been his scribe, and she would do so until he died.

In London, the Audubons lived briefly on Wimpole Street at the centre of a social whirl; the newspapers covered their arrivals and departures. Victor had a love affair with Adelaide Kemble, daughter of the actress Fanny who had likened his father to Byron. Lieutenant Augustus Bowen of the

Gulnare

, chastened after the Labrador journey, and without the promotion he had hoped for, brought around his godfather, the aforementioned Duke of Sussex. The duke wanted Parliament to buy a copy of the

Birds

, but Audubon did not pursue it.

He saw the duke as a flatterer, and did not forget that the British Museum had fallen behind on its subscription. Vincent Nolte, having lost his second fortune, passed through in pursuit of a third, this one to be made in the production of medallions of royalty.

On June 20, 1838, Robert Havell completed the last plate for Audubon’s

Birds of America

. It featured two dippers which had been shot on the Columbia River; he invented for them a backdrop of rocks and rapids. He could hardly bear to turn the page on the land of his conjuring.

The Birds of America

exists as the monument Audubon intended it to be, the monument to which he gave his life and the lives of his family. Less than two hundred copies were printed, of which 110 are known to survive. Each original subscription was accompanied by an advance payment of $220; all five folios, complete with 435 double elephant-sized prints, cost a subscriber one thousand dollars, most of which was never collected. Audubon spent more than a hundred thousand in producing the book.

W

HEN THE FAMILY

returned to America, Victor finally got to Charleston to meet the Bachmans. He too fell in love with one of John Bachman’s daughters, Eliza. Both sons married their beloveds, but within a few years, both young brides died of tuberculosis. Johnny’s wife, Maria, left two daughters for Lucy to raise, eerily replacing the girl children she had lost in their infancy. Bachman was devastated by the loss of his daughters. The friendship with Audubon, sorely tried by these losses, by the incidents with Maria Martin, and by the artist’s drinking, never recovered.

Between 1840 and 1844, the Audubon family published an octavo, or miniature version, of

The Birds of America

, an endeavour which brought in profits for the first time in Audubon’s publishing history. In 1842, Lucy and John James bought twenty-four rural acres overlooking the Hudson River at 155th Street in New York; they called it Minnie’s Land, after his pet name for his wife. Audubon began work with Bachman on another huge project,

The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America

, which in the end was completed by Johnny.

The great man grew old. Was astonished by the sight of his face in mirrors, unable to believe he had been forsaken by beauty, especially his own.

Beauty is unfair.

Beauty is poison.

H

E TOOK HIS LAST JOURNEY

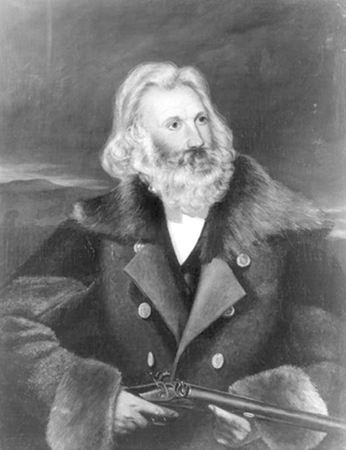

in search of quadrupeds to the eastern banks of the Missouri in 1843, where he predicted the demise of the buffalo. In his famous portrait, John Woodhouse captured the white-haired man on his return to Minnie’s Land, wearing his green coat with the fur-lined collar, now gentle-eyed and even distinguished.

The journey west to the Pacific was left to Johnny, who in 1849 rode out to the California gold rush as second-in-command of a contingent of one hundred men. His party was struck by cholera; the leader deserted, leaving Johnny to shepherd the thirty-eight surviving men across the Gila Desert to San Francisco, where they discovered they were too late for the gold. He returned home minus all his funds, without a gram of the precious metal, and his father did not recognize him.

Around his sixty-second birthday, Audubon had another of the little strokes that began, it seems, after he killed the golden eagle. He lost his sight, after which he became childlike, at once a great man and a relic. He asked the same questions over and over. He wanted lullabies sung to him. He took whiskey with his meals and hated the smell of rosewater. He stopped writing in his journal. He left his words to Lucy and his work to Johnny. In the end, the Holy Alliance owned him just as surely as he had owned them. And with equal parts pride and anger.