Crucial Conversations Tools for Talking When Stakes Are High (16 page)

Read Crucial Conversations Tools for Talking When Stakes Are High Online

Authors: Kerry Patterson,Joseph Grenny,Ron McMillan,Al Switzler

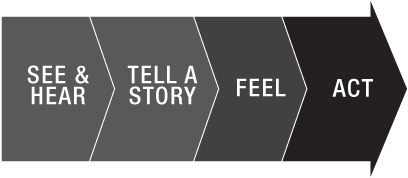

What is this intermediate step? Just

after

we observe what others do and just

before

we feel some emotion about it, we tell ourselves a story. We add meaning to the action we observed. We make a guess at the motive driving the behavior. Why were they doing that? We also add judgmentâis that good or bad? And then, based on these thoughts or stories, our body responds with an emotion.

Pictorially it looks like the model in

Figure 6-2

. We call this model our Path to Action because it explains how emotions, thoughts, and experiences lead to our actions.

You'll note that we've added telling a story to our model. We observe,

we tell a story

, and then we feel. Although this addition complicates the model a bit, it also gives us hope. Since we

and only we

are telling the story, we can take back control of our own

emotions by telling a different story. We now have a point of leverage or control. If we can find a way to control the stories we tell, by rethinking or retelling them, we can master our emotions and, therefore, master our crucial conversations.

Figure 6-2. The Path to Action

Nothing in this world is good or bad, but thinking makes it so

.

âW

ILLIAM

S

HAKESPEARE

Stories provide our rationale for what's going on

. They're our interpretations of the facts. They help explain what we see and hear. They're theories we use to explain

why, how

, and

what

. For instance, Maria asks: “Why does Louis take over? He doesn't trust my ability to communicate. He thinks that because I'm a woman, people won't listen to me.”

Our stories also help explain how. “How am I supposed to judge all of this? Is this a good or a bad thing? Louis thinks I'm incompetent, and this is bad.”

Finally, a story might also include

what

. “What should I do about all this? If I say something, he'll think I'm a whiner or oversensitive or militant, so it's best to clam up.”

Of course, as we come up with our own meaning or stories, it isn't long until our body responds with strong feelings or emotionsâafter all, our emotions are directly linked to our judgments of right/wrong, good/bad, kind/selfish, fair/unfair, etc. Maria's story yields anger and frustration. These feelings, in turn, drive Maria to her actionsâtoggling back and forth between clamming up and taking an occasional cheap shot (see

Figure 6-3

).

Figure 6-3. Maria's Path to Action

Even if you don't realize it, you are telling yourself stories

. When we teach people that it's our stories that drive our emotions and not other people's actions, someone inevitably raises a hand and says, “Wait a minute! I didn't notice myself telling a story. When that guy laughed at me during my presentation, I just

felt

angry. The feelings came first; the thoughts came second.”

Storytelling typically happens blindingly fast. When we believe we're at risk, we tell ourselves a story so quickly that we don't even know we're doing it. If you don't believe this is true, ask yourself whether you

always

become angry when someone

laughs at you. If sometimes you do and sometimes you don't, then your response

isn't

hard-wired. That means something goes on between others laughing and you feeling. In truth, you tell a story. You may not remember it, but you tell a story.

Any set of facts can be used to tell an infinite number of stories

. Stories are just that, stories. These explanations could be told in any of thousands of different ways. For instance, Maria could just as easily have decided that Louis didn't realize she cared so much about the project. She could have concluded that Louis was feeling unimportant and this was a way of showing he was valuable. Or maybe he had been burned in the past because he hadn't personally seen through every detail of a project. Any of these stories would have fit the facts and would have created very different emotions.

If we take control of our stories, they won't control us

. People who excel at dialogue are able to influence their emotions during crucial conversations. They recognize that while it's true that at first we are in control of the stories we tellâafter all, we do make them up of our own accordâonce they're told,

the stories control us

. They first control how we feel and then how we act. And as a result, they control the results we get from our crucial conversations.

But it doesn't have to be this way. We can tell different stories and break the loop. In fact,

until

we tell different stories, we

cannot

break the loop.

If you want improved results from your crucial conversations, change the stories you tell yourselfâeven while you're in the middle of the fray.

What's the most effective way to come up with different stories? The

best

at dialogue find a way to first slow down and then take charge of their Path to Action. Here's how.

To slow down the lightning-quick storytelling process and the subsequent flow of adrenaline, retrace your Path to Actionâone element at a time. This calls for a bit of mental gymnastics. First you have to stop what you're currently doing. Then you have to get in touch with why you're doing it. Here's how to retrace your path:

⢠[

Act

] Notice your behavior. Ask:

Am I in some form of silence or violence?

⢠[

Feel

] Get in touch with your feelings.

What emotions are encouraging me to act this way?

⢠[

Tell story

] Analyze your stories.

What story is creating these emotions?

⢠[

See/hear

] Get back to the facts.

What evidence do I have to support this story?

By retracing your path one element at a time, you put yourself in a position to think about, question, and change any one or more of the elements.

Why would you stop and retrace your Path to Action in the first place? Certainly if you're constantly stopping what you're doing and looking for your underlying motive and thoughts, you won't even be able to put on your shoes without thinking about it for who knows how long. You'll die of analysis paralysis.

Actually, you shouldn't constantly stop and question your actions. If you Learn to Look (as we suggested in Chapter 4) and note that you yourself are slipping into silence or violence, you have good reason to stop and take stock.

But looking isn't enough. You must take an

honest

look at what you're doing. If you tell yourself a story that your violent behavior is a “necessary tactic,” you won't see the need to reconsider your actions. If you immediately jump in with “they started it,” or otherwise find yourself rationalizing your behavior, you also won't feel compelled to change. Rather than stop and review what you're doing, you'll devote your time to justifying your actions to yourself and others.

When an unhelpful story is driving you to silence or violence, stop and consider how others would see your actions. For example, if the

60 Minutes

camera crew replayed this scene on national television, how would you look? What would

they

tell about your behavior?

Not only do those who are best at crucial conversations notice when they're slipping into silence or violence, but they're also able to admit it. They don't wallow in self-doubt, of course, but they do recognize the problem and begin to take corrective action. The moment they realize that they're killing dialogue, they review their own Path to Action.

As skilled individuals begin to retrace their own Path to Action, they immediately move from examining their own unhealthy behavior to exploring their feelings or emotions. At first glance this task sounds easy. “I'm angry!” you think to yourself. What could be easier?

Actually, identifying your emotions is more difficult than you might imagine. In fact, many people are emotionally illiterate. When asked to describe how they're feeling, they use words such as “bad” or “angry” or “frightened”âwhich would be okay if these were accurate descriptors, but often they're not. Individuals say they're angry when, in fact, they're feeling a mix of embarrassment

and surprise. Or they suggest they're unhappy when they're feeling violated. Perhaps they suggest they're upset when they're really feeling humiliated and cheated.

Since life doesn't consist of a series of vocabulary tests, you might wonder what difference words can make. But words do matter. Knowing what you're really feeling helps you take a more accurate look at what is going on and why. For instance, you're far more likely to take an honest look at the story you're telling yourself if you admit you're feeling both embarrassed and surprised rather than simply angry.

How about you? When experiencing strong emotions, do you stop and think about your feelings? If so, do you use a rich vocabulary, or do you mostly draw from terms such as “bummed out” and “furious”? Second, do you talk openly with others about how you feel? Do you willingly talk with loved ones about what's going on inside of you? Third, in so doing, is your vocabulary robust and accurate?

It's important to get in touch with your feelings, and to do so, you may want to expand your emotional vocabulary.

Question your feelings and stories

. Once you've identified what you're feeling, you have to stop and ask, given the circumstances, is it the

right

feeling? Meaning, of course, are you telling the right story? After all, feelings come from stories, and stories are our own invention.

The first step to regaining emotional control is to challenge the illusion that what you're feeling is the only

right

emotion under the circumstances. This may be the hardest step, but it's also the most important one. By questioning our feelings, we open ourselves up to question our stories. We challenge the comfortable conclusion that our story is right and true. We willingly

question whether our emotions (very real), and the story behind them (only one of many possible explanations), are accurate.

For instance, what were the facts in Maria's story? She

saw

Louis give the whole presentation. She

heard

the boss talk about meeting with Louis to discuss the project when she wasn't present. That was the beginning of Maria's Path to Action.

Don't confuse stories with facts

. Sometimes you fail to question your stories because you see them as immutable facts. When you generate stories in the blink of an eye, you can get so caught up in the moment that you begin to believe your stories are facts. They

feel

like facts. You confuse subjective conclusions with steel-hard data points. For example, in trying to ferret out facts from story, Maria might say, “He's a male chauvinist pigâthat's a fact! Ask anyone who has seen how he treats me!”

“He's a male chauvinist pig” is not a fact. It's the story that Maria created to give meaning to the facts. The facts could mean just about anything. As we said earlier, others could watch Maria's interactions with Louis and walk away with different stories.

Separate fact from story by focusing on behavior

. To separate fact from story, get back to the genuine source of your feelings. Test your ideas against a simple criterion: Can you

see

or

hear

this thing you're calling a fact? Was it an actual behavior?

For example, it is a fact that Louis “gave 95 percent of the presentation and answered all but one question.” This is specific, objective, and verifiable. Any two people watching the meeting would make the same observation. However, the statement “He doesn't trust me” is a conclusion. It explains what you

think

, not what the other person

did

. Conclusions are subjective.