Cyclopedia (27 page)

Authors: William Fotheringham

HOUR RECORD

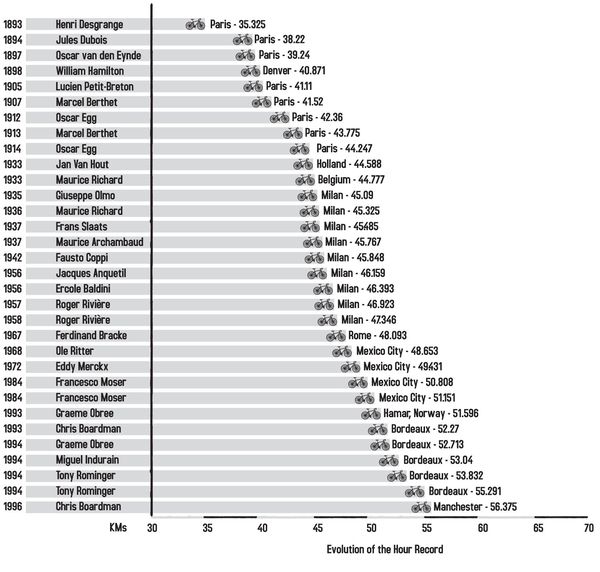

Another influential innovation from the mind of TOUR DE FRANCE founder HENRI DESGRANGE, cycling's Blue Riband withstood the test of time almost as well as the Tour, but after more than a century it was eventually rendered meaningless by official interference.

Another influential innovation from the mind of TOUR DE FRANCE founder HENRI DESGRANGE, cycling's Blue Riband withstood the test of time almost as well as the Tour, but after more than a century it was eventually rendered meaningless by official interference.

Whereas the Tour de France created its mystique by making its participants into supermen with deeds that defied most people, the Hour is simplicity itself: how far can you go in 60 minutes? And while the Tour men performed away from public gaze, mediated by journalists and televisionâeven if you see the Tour today on the road, it's only a fleeting glimpseâthe Hour has always been a public display of just what a man can physically achieve. Circling a velodrome for 60 minutes against a schedule, any show of weakness is instantly visible: if an Hour contender has to give up, that means public humiliation.

The first man to attempt the feat was JAMES MOORE, winner of the first bike races in the late 1860s. He covered 23 km on an old ordinary in Wolverhampton in 1873, but there was no world governing body to recognize the feat. Desgrange, riding on the Buffalo track in Paris 20 years later, set the first officially sanctioned distance, then retired to work as a journalist. What he left cycling was an absolute measure of what men could achieve on two wheels with the means available to them at a certain time.

The first great Hour duel lasted seven years. Just before the First World War the Swiss Oscar Egg and the Frenchman Marcel Berthet between them put 2.7 km on the distance. Egg eventually took the record over 44 km, a distance that stood for 19 years. When it was eventually beaten, the Swiss demanded that the track in Holland used by Jan Van Hout be remeasured. Initially it was ruled that Van Hout's record was short, then it was decided that the measurement had been done too low down the track, and the

record stood.

record stood.

The distance set by FAUSTO COPPI in 1942 is legendary less for the distance than for another spat over measuring, with the previous holder Maurice Archambaud, and the fact that Coppi was racing in extreme conditions, with Milan under British bombardment. The attempt was timed for the early afternoon, as the bombers tended not to attack during factory lunchbreaks.

After Coppi, the Hour became obligatory for any great: JACQUES ANQUETIL succeeded in breaking the record twice, but his second attempt was not recognized, as he refused to undergo drug testing. EDDY MERCKX set what was viewed as a definitive distance in Mexico City in 1972. He virtually had to be lifted off his bike afterward, and swore he would never attempt the record again because he had suffered so much for his 49.431 km.

Merckx had used what was then cutting-edge technology, reflecting the idea that what mattered was making the bike as light as possible. His handlebars had 48 drill holes, 95 g were saved by drilling every slot in the chain, and his bike maker Ernesto Colnago made specially light tubular tires (70 g) and used titanium for spokes, stem, and bars. Merckx also attempted to replicate the high altitude of Mexico by training in a mask so that he breathed in air with reduced oxygen content as he trained.

Athlete's Hour Record:

However, his approach was positively primitive compared with FRANCESCO MOSER 12 years later. The Italian and his 50-strong backup team paid meticulous attention to AERODYNAMICS and diet, and the outcome was that Merckx's record was smashed not once, but twice in a few days. That feat led to aerodynamic aids such as low-profile bikes, disc

wheels, and teardrop-shaped helmets becoming widely accepted.

wheels, and teardrop-shaped helmets becoming widely accepted.

The final, and perhaps finest, flurry of activity came between 1993 and 1996 when GRAEME OBREE and CHRIS BOARDMAN pushed the boundaries of aerodynamics and technology still further. Obree's radical tuck position proved that new thinking was possible in cycling, while Boardmanâand his coach Peter Keenâtook the scientific approach that was a foretaste of the British Olympic team's philosophy a few years later. That it took two of the best road racers of the 1990s, MIGUEL INDURAIN and his understudy Tony Rominger, to wrest the record from the two Britons spoke volumes about their achievements.

The Hour that stands above all the rest was also the record's last 60 minutes: Boardman's 56.375 km, set in Manchester after the 1996 Olympics using Obree's stretched out “Superman” position. Here was a man in perfect form on a machine at the limit of what was permitted at the time. “I did one minute flat for the last kilometer which is about a second off the world record,” recalled Boardman. “That is how good I felt.”

But the Hour's time was up. Cycling's governing body, the UCI, had been concerned by Obree's innovations and by Boardman's use of the radical Lotus bike (see MIKE BURROWS for more on that machine) and felt that technology was beginning to detract from the human side of cycling: the bikes were becoming more important than the men on them.

Their answer was to have two records. Any technology was acceptable in setting the Best Hour Performance, while gear similar to that used by Merckx was obligatory for the Athlete's Hour. Boardman's final feat before retirement was to break, narrowly, Merckx's distance, but the next beating of the hour, by the Russian Ondrej Sosenka, barely made headlines. Meanwhile, the legal niceties of what equipment could and could

not be usedâthere was debate over pulse monitors and cycle computers, for exampleâmade future hour attempts akin to tiptoeing through a bureaucratic minefield.

not be usedâthere was debate over pulse monitors and cycle computers, for exampleâmade future hour attempts akin to tiptoeing through a bureaucratic minefield.

Further reading/viewing:

The Hour:

The Hour:

Sporting Immortality the Hard Way

, Michael Hutchinson, Yellow Jersey, 2006; DVD:

The Final Hour

, Michael Hutchinson, Yellow Jersey, 2006; DVD:

The Final Hour

HOY, Sir Chris

Born:

Edinburgh, Scotland, March 23, 1976

Edinburgh, Scotland, March 23, 1976

Â

Major wins:

Olympic gold sprint, team sprint, kilometer 2008; Olympic gold kilometer 2004; Olympic silver team sprint 2000; world champion sprint 2008, Keirin 2007â8; kilometer 2002, 2004, 2006, 2007, team sprint 2002, 2005; Commonwealth champion, kilometer, 2002, team sprint 2006; MBE 2004; knighted 2008

Olympic gold sprint, team sprint, kilometer 2008; Olympic gold kilometer 2004; Olympic silver team sprint 2000; world champion sprint 2008, Keirin 2007â8; kilometer 2002, 2004, 2006, 2007, team sprint 2002, 2005; Commonwealth champion, kilometer, 2002, team sprint 2006; MBE 2004; knighted 2008

Â

Nickname:

the Real McHoy

the Real McHoy

Â

Further reading:

Heroes, Villains and Velodromes

, Richard Moore, Harpersport, 2008;

Chris Hoy, the Autobiography

, Chris Hoy, Harper Collins UK, 2010

Heroes, Villains and Velodromes

, Richard Moore, Harpersport, 2008;

Chris Hoy, the Autobiography

, Chris Hoy, Harper Collins UK, 2010

Â

The greatest cycling Olympian GREAT BRITAIN has produced, winner of three Olympic gold medals at the Beijing Games in 2008, and the first cyclist to be elected BBC Sports Personality of the Year since TOM SIMPSON in 1965. Hoy began his cycling life as a juvenile BMX star and moved to mountain-biking and road racing before becoming a track racer at the Meadowbank velodrome in Edinburgh, taking a silver medal in the British junior sprint championship in 1994. Hoy's career was transformed when national lottery funding arrived in British cycling in 1997; he was one of the early beneficiaries of the World Class Performance Plan put together by CHRIS BOARDMAN's trainer Peter Keen.

Together with Jason Queally and Craig Maclean, he made the initial breakthrough with a silver medal in the team sprint at the 1999 world championship in Berlin. The Sydney Olympic Games a year later saw Queally take kilometer gold while Hoy, Queally, and Maclean raced to silver in the team sprint. Hoy's breakthrough year was 2002, with gold medals in the kilometer and team sprint at the world championship. In 2004 he took the kilometer gold at the Athens Games, only for the UCI to drop the event from the Olympic program. Even so, Hoy then added a further six world titles in the next three years, including the world sprint championship in Manchester in 2008. No Briton had won the title since REG HARRIS in 1954.

In 2007 Hoy traveled to the Bolivian capital, La Paz, to attack

the Frenchman Arnaud Tournant's standing start kilometer record. The Scot was warned before he rode that there was a risk he might collapse afterward with pulmonary edema, a buildup of fluid on the lungs. Oxygen canisters and an oxygen-filled body-bag were on standby. The velodrome there is poorly maintained: the surface is bumpy and before Hoy made his bid, the waist-high grass in the track center had to be cut with scythes.

the Frenchman Arnaud Tournant's standing start kilometer record. The Scot was warned before he rode that there was a risk he might collapse afterward with pulmonary edema, a buildup of fluid on the lungs. Oxygen canisters and an oxygen-filled body-bag were on standby. The velodrome there is poorly maintained: the surface is bumpy and before Hoy made his bid, the waist-high grass in the track center had to be cut with scythes.

Hoy's attempt cost tens of thousands of poundsâhe made no money out of it for himself, the sponsorship cash all went into logisticsâtook a year's planning, and ended in relative failure when he failed, twice, to beat Tournant's time, falling short by just 0.005 seconds on his second attempt. Smashing the 500 m record was meager compensation, but recordbreaking is an unforgiving business.

Beijing was the climax of his career, however. The gold rush began on day one with a blistering team sprint together with Jamie Staff and the virtually unknown Jason Kenny. The trio recorded 42.95 seconds in qualifying, the fastest time ever recorded for the three-man, three-lap effort, which broke the spirit of their main rivals, the French and Australians. The final was a formality; as was Hoy's title in the KEIRIN the following day. From the previous year's world championship in Palma, Mallorca, he had developed his own style, attacking early and relying on his strength to keep him ahead of the opposition. The silver medal went to another Scot, Ross Edgar, on a day when Great Britain landed seven medals.

The third event was the most prestigious of the series, the match sprint, and in the final Hoy was pitted against Kenny, who was no match for the older man. On taking gold number three the Scot collapsed into the arms of his father, David, and dissolved into tears prompting the headline: “The Great Bawl of China.” “We try to act like robots, to keep our emotions capped throughout the whole process. That's why it all came out afterwards,” Hoy later explained.

Hoy is outwardly mild-mannered and genial, but inside he is a driven man. “Bottom line, he's selfish,”

said performance manager Shane Sutton. “He's a gentle giant with the big Mike Tyson neck. He's a trainoholic: he loves getting up, going to work and leaving everything on the track.” Hoy worked with the team psychiatrist Steve Peters in the buildup to the Athens Olympics to overcome his nervesâthe kilometer is a waiting game, when you have to watch the opposition performing which can be intimidating. “There's a myth that sports people are very self-confident but I'd say a high percentage are wracked with self-doubt. Ten minutes before the start you'd rather be anywhere else.” Hoy wrote his MEMOIRS in 2009 and as the London Games hove into view, he was hinting that his best days might be yet to come.

said performance manager Shane Sutton. “He's a gentle giant with the big Mike Tyson neck. He's a trainoholic: he loves getting up, going to work and leaving everything on the track.” Hoy worked with the team psychiatrist Steve Peters in the buildup to the Athens Olympics to overcome his nervesâthe kilometer is a waiting game, when you have to watch the opposition performing which can be intimidating. “There's a myth that sports people are very self-confident but I'd say a high percentage are wracked with self-doubt. Ten minutes before the start you'd rather be anywhere else.” Hoy wrote his MEMOIRS in 2009 and as the London Games hove into view, he was hinting that his best days might be yet to come.

(SEE ALSO

TRACK RACING

,

OLYMPIC GAMES

)

TRACK RACING

,

OLYMPIC GAMES

)

HUMAN POWERED VEHICLES

The International Human Powered Vehicle Assocation was founded in California in 1975. HPVs are in essence any cycle with aerodynamic parts that fall outside UCI rules. These can include conventional diamond-frame bikes with fairings to enhance AERODYNAMICS, or RECUMBENT machines that offer a lower profile. The HPV HOUR RECORD is 87.123 km, set in 2008; compared with the conventional bike record of 49.7 km, the speed advantage speaks for itself.

The International Human Powered Vehicle Assocation was founded in California in 1975. HPVs are in essence any cycle with aerodynamic parts that fall outside UCI rules. These can include conventional diamond-frame bikes with fairings to enhance AERODYNAMICS, or RECUMBENT machines that offer a lower profile. The HPV HOUR RECORD is 87.123 km, set in 2008; compared with the conventional bike record of 49.7 km, the speed advantage speaks for itself.

Other books

A Midsummer Night's Dream by William Shakespeare

Baiting the Maid of Honor by Tessa Bailey

Cybersong by S. N. Lewitt

Second Lives by Sarkar, Anish

Cold as Ice by Anne Stuart

Nano Contestant - Episode 1: Whatever It Takes by Leif Sterling

Vanishing Act by Barbara Block

Escapement by Lake, Jay

Women in Deep Time by Greg Bear

Dreamer's Pool by Juliet Marillier