Cyclopedia (30 page)

Authors: William Fotheringham

L

LEMOND, Greg

Born:

Lakewood, California, June 26, 1961

Lakewood, California, June 26, 1961

Â

Major wins:

World road championship 1983, 1989; Tour de France 1986, 1989, 1990, five stage wins

World road championship 1983, 1989; Tour de France 1986, 1989, 1990, five stage wins

Â

Interests outside cycling:

wine, cross-country skiing

wine, cross-country skiing

Â

Further reading:

Greg LeMond, The Incredible Comeback

, by Samuel Abt (Stanley Paul, 1991)

Greg LeMond, The Incredible Comeback

, by Samuel Abt (Stanley Paul, 1991)

Â

Â

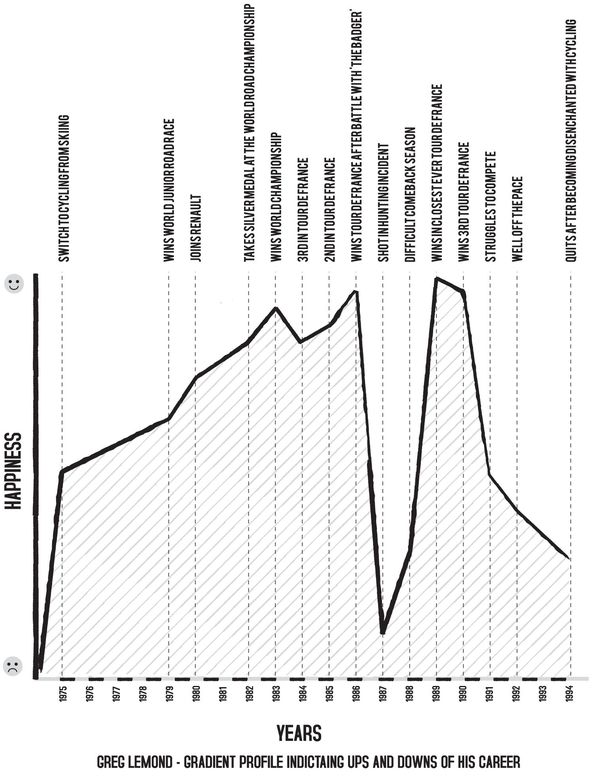

The first American winner of the TOUR DE FRANCE, the author of one of the sport's most dramatic comebacks, the victor of perhaps the most epic Tour ever, and one of the men who did most to change professional cycling in the late 20th century, LeMond was not the first American to finish the Tour; that honor goes to Jonathan Boyer (see UNITED STATES). But he was the first American to win the professional world championship, in 1983, and the first US Tour winner when he finally triumphed in a race-long battle with his own teammate BERNARD HINAULT.

Like many American cyclists, LeMond's background was middle class; his father, Bob, was a real estate agent. Initially LeMond was a downhill skier, but he switched to cycling at 14, and by 18 he had won the world junior road race. A year later, he was a professional with the Renault-Elf team, led then by Hinault and managed by Cyrille Guimard (see TEAMS for more on Renault and other great squads); in 1982 he took the silver medal at the world road championship and won the Tour de l'Avenirâa “mini-Tour de France” for young ridersâwhile in 1983 he rode to a solo win in the world championship at Altenrhein, Austria.

LeMond's Tour debut came in 1984, when he finished third behind his team leader LAURENT FIGNON and Hinault, who had moved to the La Vie Claire squad. In 1985 he joined Hinault, on a three-year deal that was cycling's first million-dollar contract, with the understanding that he would help Hinault win that year's Tour and the Frenchman would assist him in 1986. In 1985 LeMond looked the strongest in the final week, at one point being told to soft-pedal when he was in a key breakaway, and had the chance of taking the yellow jersey.

The 1986 race turned into a psychological battle with Hinault, who attacked continually, insisting as he did so that he was softening up LeMond's rivals and helping his protégé become a stronger, harder cyclist. At one point, Hinault had a four-and-a-half-minute overall lead, but the Frenchman cracked in the Alps before escaping with LeMond on the climb to l'Alpe d'Huez, where they crossed the line with their arms around each other's shoulders. But Hinault still would not say the Tour was over, and there were even accusations that someoneâa French fan?âhad tampered with the American's bike. To this day LeMond believes Hinault was trying to win the race for a record sixth time; “the Badger,” on the other hand, still maintains he could have won the race if he had wanted, but he was helping LeMond.

The American was only 25 and seemingly set for a long reign over the Tour, but the following spring he was shot in a hunting accident in California, losing a large amount of blood, suffering a partially collapsed lung, and ending up with pellets in his intestine, liver, and diaphragm; 30 of them are still there. He was 20 minutes from death; by sheer chance a highway patrol helicopter was nearby and he was airlifted quickly to a trauma hospital.

His comeback was painful; 1988 was fallow, and he suffered in the early part of the 1989 season before returning to his best in the 1989 Tour, a three-way battle with Pedro Delgado and LeMond's former team leader Fignon. The lead oscillated between LeMond and the Frenchman while Delgado strove to recover three minutes he had lost on the opening day when he

turned up late for the prologue time trial. Finally, LeMond won the race when he used new aerodynamic handlebars to overturn a 50 second deficit on Fignon in the final day's time trial to the Champs-Elysées; his 8-second advantage was the closest in Tour history.

turned up late for the prologue time trial. Finally, LeMond won the race when he used new aerodynamic handlebars to overturn a 50 second deficit on Fignon in the final day's time trial to the Champs-Elysées; his 8-second advantage was the closest in Tour history.

Four weeks later, on a rainy day in the French Alps, he outsprinted Russian Dimitri Konychev and SEAN KELLY for the world championship, sealing his incredible comeback. The upshot of that was cycling's biggest-ever contract: a $5.5 million plus bonuses deal with French team Z, backed by a clothing company. That contract dragged cycling into the modern world, where at last realistic payments were given to its top performers.

In 1990 LeMond took a third Tour, matching Louison Bobet; at the time only EDDY MERCKX, Hinault, and JACQUES ANQUETIL had done better. But in 1991 and 1992 LeMond struggled, something that he now interprets as being down to the arrival of a new drug in the peloton, EPO, and he quit in 1994, disenchanted with his final years in the sport.

LeMond was one of the most innovative cyclists of the 20th century, on a par with FAUSTO COPPI in the way he pushed the sport forward. As well as being the first professional cyclist to use “triathlon” handlebars in time trials (see AERODYNAMICS), LeMond helped to popularize hard-shell cycle helmets, regarded with some suspicion when he began using them in 1990 but now universal. He also pioneered communication with the team car via mini-radios, rode titanium frames, and experimented with handlebar design in collaboration with the Scott company. He was also the first cyclist to ride the PAR I SâROUBAIX Classic using MOUNTAIN BIKE front suspension forks. Not surprisingly, he ended up with his own cycle company.

LeMond was the first star cyclist to break with the European belief that cyclists should be subservient to promoters, race organizers, and team managers, in essence an attitude that went back to the postwar years when the stars had come from blue-collar stock and reckoned they were lucky to be racing at all. He brought his family

with him to races, breaking a huge taboo, raised eyebrows by getting an agent (his father) to negotiate his contracts, and insisted on doing things his way, whether that meant eating McDonald's occasionally or bringing his own portable air conditioner to hotels on the Tour de France.

with him to races, breaking a huge taboo, raised eyebrows by getting an agent (his father) to negotiate his contracts, and insisted on doing things his way, whether that meant eating McDonald's occasionally or bringing his own portable air conditioner to hotels on the Tour de France.

He had a close-knit inner circle around him: a grumpy Belgian mechanic, Julien de Vries, who had worked with Merckx and would go on to wield a wrench for LANCE ARMSTRONG, and the distinctive figure of Mexican SOIGNEUR Otto Jacome, who had the biceps of a boxer and wore a floppy Stetson. And LeMond brought a certain eccentricity with him; in the 1991 Tour he decided to take a special carbon-fiber bike up to his hotel bedroom but neglected to tell the Z team mechanics. De Vries was in tears, convinced the machine had been stolen, and a second mechanic was dispatched to Parisâfrom eastern Franceâto get a replacement. This was before the era of mobile phones: when the mistake was discovered, the police had to be sent to chase down the mechanic as he sped down the autoroute.

LeMond's life after retirement was as turbulent as before. He came close to divorcing his wife Kathy, he revealed that he had been abused as a child, and he made a dramatic intervention in the 2006 Tour winner Floyd Landis's doping hearing. He also became a critic of seven-time Tour winner Lance Armstrong. He attacked the Texan over his work with the controversial trainer MICHELE FERRARI, alleged that Armstrong had said LeMond could not have won the Tour without using EPOâwhich Armstrong deniesâand raised questions about Armstrong's personal antidoping program when the seven-time Tour winner made his comeback in 2009.

LETH, Jorgen

(b. Denmark, 1937)

(b. Denmark, 1937)

Danish poet and film director best known in cycling for three documentaries:

Stars and Watercarriers

(1974),

The Impossible Hour

(1974), and

Sunday in Hell

(1977). His work has lent a whole new dimension to cycling and sports documentary: deeply impressionistic, epic in tone but very human, with the interplay of music and action footage playing a key role. Leth has also written 10 volumes of poetry and 8 nonfiction works, including his controversial autobiography

The Imperfect Man

. He has been chairman of the Danish film institute and commentated on some 20 Tours de France for television. He has lived in Haiti since 1991 and was honorary Danish consul on the island between 1999 and 2005.

Stars and Watercarriers

(1974),

The Impossible Hour

(1974), and

Sunday in Hell

(1977). His work has lent a whole new dimension to cycling and sports documentary: deeply impressionistic, epic in tone but very human, with the interplay of music and action footage playing a key role. Leth has also written 10 volumes of poetry and 8 nonfiction works, including his controversial autobiography

The Imperfect Man

. He has been chairman of the Danish film institute and commentated on some 20 Tours de France for television. He has lived in Haiti since 1991 and was honorary Danish consul on the island between 1999 and 2005.

Stars and Watercarriers

tells the tale of the 1973 GIRO D'ITALIA, focusing on the conflict between EDDY MERCKX and the little climber Jose-Manuel Fuente. It is split into 10 “chapters” including “the trial of truth,” centered on a time trial involving the Danish star Ole Ritter. The pursuiter/time triallist is also the key figure in

The Impossible Hour

, about his three attempts to break the HOUR RECORD in Mexico City in 1974.

Sunday in Hell

centers on the 1976 PARISâROUBAIX and is Leth's defining cycling work. He shot the event from all angles and included a now legendary sequence with the cyclists bouncing in slow-motion over the cobbles. Cycling also features in Leth's 1973 film

Eddy Merckx in the Vicinity of a Cup of Coffee

, a surreal mix of the director reading his poetry while subtitles deliver comment; the second half of the film includes footage from the 1970 TOUR DE FRANCE.

tells the tale of the 1973 GIRO D'ITALIA, focusing on the conflict between EDDY MERCKX and the little climber Jose-Manuel Fuente. It is split into 10 “chapters” including “the trial of truth,” centered on a time trial involving the Danish star Ole Ritter. The pursuiter/time triallist is also the key figure in

The Impossible Hour

, about his three attempts to break the HOUR RECORD in Mexico City in 1974.

Sunday in Hell

centers on the 1976 PARISâROUBAIX and is Leth's defining cycling work. He shot the event from all angles and included a now legendary sequence with the cyclists bouncing in slow-motion over the cobbles. Cycling also features in Leth's 1973 film

Eddy Merckx in the Vicinity of a Cup of Coffee

, a surreal mix of the director reading his poetry while subtitles deliver comment; the second half of the film includes footage from the 1970 TOUR DE FRANCE.

Leth was also involved in an abortive attempt to make a feature film about the Tour de France starring Dustin Hoffman; footage was shot on the 1986 Tour, but the film never saw the light of day.

Â

(SEE

FILMS

FOR MORE CYCLING ON CELLULOID)

FILMS

FOR MORE CYCLING ON CELLULOID)

Â

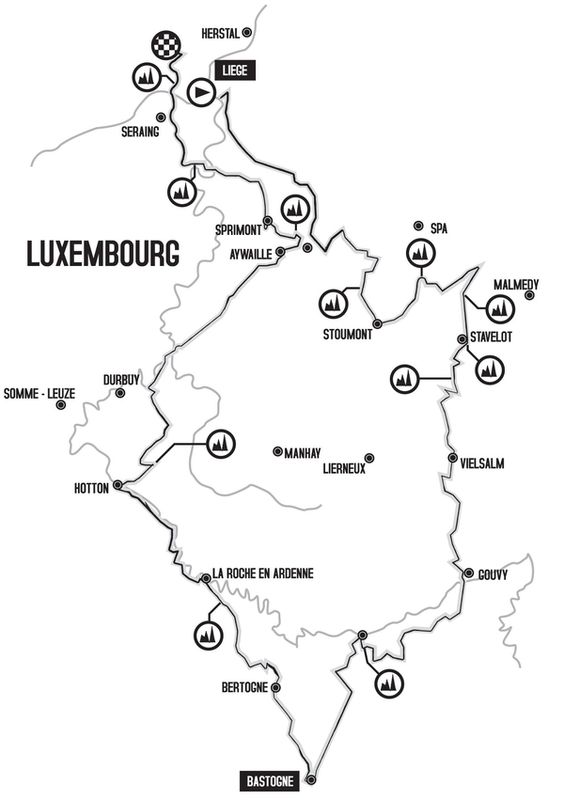

LIÃGEâBASTOGNEâLIÃGE

The oldest CLASSIC on the cycling calendar, nicknamed

la doyenne

because it dates back to 1892. The route was chosen mainly because Bastogne, 50-odd miles south of Liège through the Ardennes hills, was the farthest anyone could get to and return by train in a day, which meant that an official could be sent to manage the checkpoint there. There were several years when the race was not run, and it gained true prestige only when it began to be run the day after a neighboring race, Flèche Wallonne (see Classics), with an overall classification known as the Ardennes Weekend. The DOUBLE in the two races is a rare and coveted feat.

la doyenne

because it dates back to 1892. The route was chosen mainly because Bastogne, 50-odd miles south of Liège through the Ardennes hills, was the farthest anyone could get to and return by train in a day, which meant that an official could be sent to manage the checkpoint there. There were several years when the race was not run, and it gained true prestige only when it began to be run the day after a neighboring race, Flèche Wallonne (see Classics), with an overall classification known as the Ardennes Weekend. The DOUBLE in the two races is a rare and coveted feat.

The race's distinctive feature is the succession of small but tough climbs through the Ardennes hills, where American and German forces fought the Battle of the Bulge in 1944. The hills start well before halfway at the town of Houffalize, where the US Army completed its encirclement of the Germans; the final phase begins with the toughest climb on the course, La Redouteâwhere a plaque celebrates the race and its ridersâwhich is followed by four or five more ascents before the finish, most recently held above Liège in the suburb of Ans.

The

doyenne

is now a tactical battle, but the past has witnessed epic lone victories for EDDY MERCKX, in 1969, when he broke away with one of his

domestiques

60 miles from the finish, and JACQUES ANQUETIL, who took his best one-day win there in 1966. The weather is often a factor as the race crosses the high hills, notably in BERNARD HINAULT's 1980 win, on a day of snow and ice that Pierre Chany described as “phantasmagoric.” Only 40 of the 150-rider field were still in the race after the first 40 miles and Hinault rode the final 40 miles alone to win by nine minutes. Two joints in the fingers of his right hand remain numb to this day. The best specialist in Liège is the Italian Moreno Argentin, winner four times between 1985 and 1991.

doyenne

is now a tactical battle, but the past has witnessed epic lone victories for EDDY MERCKX, in 1969, when he broke away with one of his

domestiques

60 miles from the finish, and JACQUES ANQUETIL, who took his best one-day win there in 1966. The weather is often a factor as the race crosses the high hills, notably in BERNARD HINAULT's 1980 win, on a day of snow and ice that Pierre Chany described as “phantasmagoric.” Only 40 of the 150-rider field were still in the race after the first 40 miles and Hinault rode the final 40 miles alone to win by nine minutes. Two joints in the fingers of his right hand remain numb to this day. The best specialist in Liège is the Italian Moreno Argentin, winner four times between 1985 and 1991.

Other books

The Narrows by Michael Connelly

Glamorous Illusions by Lisa T. Bergren

Summer Evenings at the Seafront Hotel: Exclusive Short Story by Vanessa Greene

Guía del autoestopista galáctico by Douglas Adams

And the Burned Moths Remain by Benjanun Sriduangkaew

Fly on the Wall by Trista Russell

Revenge of the Tiki Men! by Tony Abbott

When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi

PsyCop 4: Secrets by Jordan Castillo Price