Daily Life During The Reformation (20 page)

Read Daily Life During The Reformation Online

Authors: James M. Anderson

A wealthy family dressed servants in uniforms, but

conditions were often abysmal. Sometimes they were forced to sleep in dark

hovels and often on the ground with only a blanket. Anyone who stole from the

master was subject to hanging.

LIGHT AND WARMTH

Oil lamps or candles were used for light. For most people,

the candles were made of suet, emitting an odious smell. More expensive wax

candles were only used by the wealthy. There was no lighting in the streets at night,

so people carried a torch or lantern and a weapon of some kind. Although sulfur

matches were known at the time, they were seldom used.

It was generally not common to heat more than one room, so

in winter, the bourgeois family tended to concentrate in the kitchen where food

was cooked and where there was always some warmth available from the large

fireplace and chimney that radiated heat. The whole family sat on stone benches

around the fire, which also provided some light during the long evenings.

French people had long envied the Germans who had great

wood-burning stoves. Since the time of Franc

o

is I, some royal houses

in France had them; but in general, it was only toward the end of the sixteenth

century that such stoves became more easily accessible to lower class society.

Churches were always freezing, and this was sometimes

offset by braziers carried for prayers or for the service. A metal ball filled

with hot embers proved a blessing for the numb fingers of the priest. Warming

pans, some could be very large and made of silver, were used by well-off

families before retiring to an icy cold bed.

Bells were used to signify the time to light fires for heat

and light. Those of Notre Dame in Paris rang at seven o’clock, the ones at

Saint-Germaine at eight, and the bells of the Sorbonne at nine. An ordinance of

1596 fixed the curfew at seven after the feast of Saint-Remi up to Easter and

at eight after Easter.

Fire-fighting equipment was, at best, rudimentary, although

reservoirs installed on the roofs of buildings saved rain water, and an

attached pump was used against the frequent fires.

Everyone seemed to be afraid of lightning, and many people

carried a piece of coral or eagle feathers for protection. Masts of ships were

protected on the upper end by sealskins, as it was widely believed that

lightning never struck eagles, seals, crocodiles, turtles, or fig and laurel

trees.

WATER AND CLEANLINESS

Some places in Paris, such as hotels, schools, colleges,

and certain convents and monasteries had private water channels granted by

royal patent after 1598. In addition, there were some houses with their own

private wells, but their water was sometimes contaminated and dangerous to

drink. Those who could afford it employed water carriers or recruited their valets

to bring buckets of water from the public fountains fed by aqueducts around the

city. Lower classes collected their own water from the Seine River, the

recipient of runoff from the streets and sewers in Paris, but no doubt, they

were immune to the germs and used to its foul smell.

On average, the bourgeois house used about 15 buckets of

water daily that sometimes had to be carried up steep stairs to the third or

fourth floor of a building. Once it reached the apartment, it was poured into

recipients. Water was a precious commodity and not to be wasted. Its primary

use was in the kitchen for cooking and sometimes drinking, but it was not for

personal hygiene. Taking a bath was out of the question short of being struck

down with some terrible disease that required one. Many dwellings did not have

even a washing bowl; a bathroom towel was unknown. Normally, people cleaned

themselves by rubbing, scraping, and scratching their skin, or through

perspiration—hence, public steam rooms were popular. They were not favored by

either Catholic or Protestant clergy who denounced the steam parlors as places

of debauchery and sin.

Few people washed except once in a while, their hands and,

less often, their feet. They never washed their heads. Jean Duchesne, one of

the queen’s doctors, recommended cleaning the head, the ears, and scrubbing

one’s teeth. After eating, he suggested washing out the mouth with pure wine

and washing the hands in cold water. Even better for the hands was to mix the

water with wine or sage leaves that had been soaked overnight. In winter it was

recommended to use warm water to wash the hands. The water could be warmed by

rinsing it in the mouth. To clean the teeth one could also employ lentisque

from the pistachio tree, rosemary, or some other aromatic wood. Most important,

however, was to thank God after each meal.

The population customarily suffered from lice, fleas,

bedbugs, and other vermin, and gentlemen suffered these parasites under their

gold-braided jackets as much as the beggars under their rags. It was always

difficult to refrain from scratching one’s head, chest or other places when in

polite company. When people complained to doctors about their parasites, they

were told that to drive away fleas, they should attach several heads of kippered

herring to a wire and put them under their straw mattresses.

People were warned not to spit or blow their nose at meals

without turning one’s head aside, away from the table. One must not attempt to

catch fleas while dining, and when eating in company, everyone should refrain

from scratching the head.

ECCONOMIC CHANGES

At the beginning of the sixteenth century, as wealth began

to be generated outside of property, the bourgeois soon came to equal and even

surpass many nobles and high clerics in the accumulation of money.

Commoners were less seeking to demonstrate wealth by gaudy

refinements and showy purchases enjoyed by the nobility but preferred to amass

movable wealth. War was not on their agenda, the profession of war was left to

the nobility, and they shunned ostentatious activities preferring to increase

their monetary holdings. Frugal, modest, and avaricious, money brought them

power, and they gradually took over the municipal administrations in the name

of the king and then gained control of provincial assemblies and tribunals. The

bourgeois took part in public parades and ceremonies. During the religious and

civil wars from 1562 to 1598, the middle class reached new heights of

prosperity.

Rich speculators and financiers found positions as ministers

of the king and married the daughters of upper class families, or they

purchased noble rank from the monarchy. Less successful merchants could only

watch with envy.

Among the poor, the lowest classes, wages did not keep pace

with inflation. The debasement of coins by the crown and the hoarding of wheat

by merchants waiting for higher prices hurt the laborers both rural and urban.

To make matters worse, French migrants flowed into Spain where wages were

higher and sent home silver imported from the New World causing inflationary

spirals. The peasantry faced increasing taxes by royal agents and those of the

Huguenots, while many lost their land to money lenders and the elite. Thousands

of landless people roamed the countryside destitute and miserable, harassed by

ever-threatening laws against vagabondage. Once the civil wars were over in

1598, and peace returned to the realm, the peasantry, revitalized, began to

flourish again.

OUTWITTING THIEVES

France was a dangerous place. In 1595, the Englishman, Fynes

Moryson, walked throughout the country and described his experiences. At one

point along the way, he ran into some demobilized soldiers on their way home

from a war. Moryson had hidden his gold inside his inner doublet, but the

soldiers took this along with his shirt, sword, and cloak, leaving him

practically naked. He was not completely destitute, however, since he had

shortly before sold his horse for sixteen French crowns, which money he had put

in a box, covering them over with a putrid-smelling ointment for scabs. A

further six crowns he had wrapped in a cloth, which he tied up with thread

sticking some needles into it. As they were stripping him of his clothes, the

thieves took the box, but when they smelled the contents, they threw it on the

ground. At the same time, seeing no use for the thread, they trampled it

underfoot. As they rode away, a relieved Moryson retrieved his money, grateful

at least to be spared having to beg in a foreign country.

9 - NETHERLANDS

On

his retirement in 1556, Charles V split the empire, whereby his brother became

Holy Roman Emperor as Ferdinand I, and his son inherited Spain, the

Netherlands, Spanish territories in Italy, and the Americas, as Felipe II.

Netherlanders soon began to despise their new religiously fanatic sovereign who

taxed the commerce and appointed his own officials in secular and

ecclesiastical posts. Felipe said he would die a hundred deaths rather than

rule over heretics. But heretics there were and in growing numbers. People had

been arrested for failing to attend Easter Communion, and bloody persecutions

took place in Flanders.

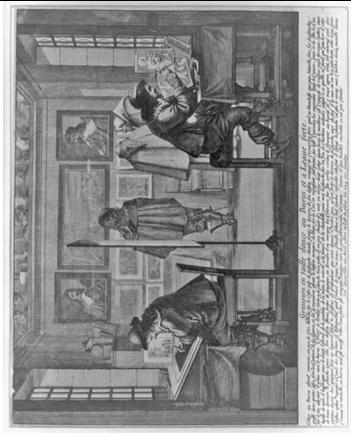

Etcher and engraver in studio

with patrons.

SPANISH PERSECUTION

There were many grievances against Spanish rule under

Felipe II, whose half sister, Margaret, Duchess of Parma, acted as regent from

1559–1567.

The duchess’ chief advisor, Cardinal Granville, alienated

the nobles in the early 1560s when he reorganized the bishoprics, Felipe II’s

nominees, to give the prelates more power on councils of state and introduced

the Inquisition to bring an end to Protestantism. The nobility and city

councils of the Netherlands considered this in direct violation of their

rights.

Margaret attempted to enforce the heresy laws in 1565 such

as the placard laws introduced earlier that prohibited reading heretical

literature on pain of death.

But the masses openly decried the injustices of Spanish and

Church rule, opposing the tithe, high prices, taxes, the imposition of the Inquisition

in the Netherlands, and other arbitrary acts. They hated the self-serving

Catholic clergy, who never lacked a good meal. Pamphlets began circulating,

mocking and satirizing the clergy and the Church. The disparity in wealth was

clear: a laborer earned about 75 guilders a year, while the Prior of the

Batavian Monastery received 7,500 guilders annually. Churches and monasteries

administered huge financial sums, and many of them owned at least half of all

peasant farms. Exempt from taxation, the Church demanded a tenth of the grain,

cattle, and fruit produced from the fields and orchards.

The steady influx of Calvinist disciples into the

Netherlands around the middle of the century led to Protestant congregations

springing up throughout the country.

VIOLENT ACTION AND REACTION

On August 10, 1566, in a field near the town of Steenvorde

in Flanders, a crowd gathered to listen to the words of a Protestant preacher.

Fired up by his ringing condemnations of injustice and led by a former monk,

the mob gathered up axes, ladders, ropes, and hammers and marched off shouting

and singing hymns to the nearest monastery. The monks fled for their lives, and

the building was reduced to rubble. Within a week, 400 churches, monasteries,

and convents were attacked. Icons statues, pews, and choir stalls were hacked to

bits: pictures were ripped from walls, altars smashed, windows broken, curtains

shredded, columns battered down, and even the holy crosses were destroyed. In

the big cities, church services stopped. Terrified priests and nuns dared not

appear before the avenging crowds and hid as best they could.

The rioters rang the bells constantly, and when tired from

their days’ work, they carried home whatever they pleased from the holy sites.

A swath of destruction lay across the land. Beautiful objects, paintings, and

precious, richly decorated manuscripts were not spared. In the frenzy, private

homes were not immune, and people buried their sacred treasures in back yards

to preserve them.

As the Lutheran doctrine spread and people began to think

of themselves as free men with no allegiance but to God, they refused to doff

their hats and kneel in streets when a religious procession passed by. The long

burning fuse of discontent had reached the powder keg.