Daily Life During The Reformation (22 page)

Read Daily Life During The Reformation Online

Authors: James M. Anderson

Extinguishing a fire once it had taken hold was nigh

impossible. People of all ages would arrive when the fire alarm was sounded,

forming lines along which buckets of water were passed to be thrown on the

blaze. Others would try to stop it spreading by tying wet cloths to the end of

a stick to put out sparks that landed in the thatch of a nearby house. In a

strong wind, such measures were almost useless.

The essential ingredient, water, had to be always available

to put out fires, and in winter when the rivers, streams, and canals were

frozen over, it was necessary to make sure there were openings in the ice from

which to draw it. In many communities, leather sacks of water were kept in the

houses for emergencies. In case of a fire, every household had to supply an

able-bodied person to bring pails for carrying water. It was also mandatory to

hang a lantern in front of every house in order to light up the dark streets if

the fire alarm sounded at night. Houses with thatched roofs also had to have

ladders standing by. When ordered by the city, everyone was required to have a

two-handled tub of water outside the front entrance, and inspectors came around

to take inventory and ensure compliance.

Gradually, in the course of the sixteenth century, more and

more houses were built of stone, and thatch gave over to tiled or slate roofs.

Outlets for smoke made of wood were replaced by brick chimneys.

HYGIENE

The back yards of houses were usually places to store

unused articles in sheds along with housing pigs, chickens, and a cow or horse.

There also would be hung the laundry, which would be done four or five times a

year. Pots hung from the gutter of the roof for nesting birds, generally

starlings, and when the young birds were nearly ready to leave the nest, they

were gathered up and eaten.

Streets were a dumping ground for just about everything:

kitchen leftovers, broken pottery, or china were thrown outside, and horses,

cattle, chickens, and pigs left their droppings as they wandered through the

smelly mess. If there was a canal or stream at the doorway, refuse was thrown

into that. Outhouses were constructed over the water, and sometimes there would

be a little landing next to it where pots and pans were washed.

Towns were infested with rats that ate the grain, cheese,

fruit, or whatever else was available. They also gnawed the woodwork in the

houses. Although they were not identified as carriers of disease, people tried

ingenious ways to be rid of them. One device was a narrow, about seven-foot-long,

wooden box with an opening at each end and compartments inside filled with

nesting material. Once the compartments were full of rats, the ends were sealed

and the animals drowned. Another was a plate balanced on two sticks of wood

extending out from the kitchen counter. When the rat walked onto the plate to

retrieve the bait placed on it, the plate tipped up and the rat fell into a

bucket of water placed underneath. There were many such devices, but the rats

bred faster than they could be eliminated. The streets, mostly unpaved, were a

moving mass of rodents at night that would begrudgingly make way for the night

watchman.

Bathing

Water was a precious commodity not because it was scarce,

but it had to be carried, usually by hand, from the source to the house. It was

used sparingly for washing the body, but when it was absolutely necessary, a

large wooden tub was available for the purpose. It was a time-consuming

operation pouring pots and pitchers of hot water into the tub and then sitting

there for a while, sprinkling some of it over one’s head in an attempt to wash

the hair. It was apparently more fun, although more costly, to go to the public

bathing house at the local inn where men and women climbed into the same tubs,

pots of beer in hand, to enjoy the bath and the company, much to the

disapprobation of the Church.

THE INFIRM

Mentally deficient people and those suffering from diseases

were found in abundance on the streets of Holland including many who were too

sick to work and others such as lepers, who were obliged to shake the lepers’

wooden clapper as they approached to beg, to alert the prospective almsgiver of

their condition. As the Reformation gained momentum, however, life became more

difficult for those in need. Having heard from the reformers that salvation

depended on God’s grace and not on good deeds, the latter became less popular

as people liked the idea that it was not necessary to give alms in order to go

to heaven.

There were people about who begged that appeared

handicapped but were in fact fit and sound. They would complain of having

suffered in the wars, women pretended to faint in the streets, and some would

lie down in front of the doors of residences, groaning and crying out. Some

women carried tiny babies saying they had just given birth and needed rest and

food. Others pretended insanity or faked an attack in the market place, and

when the audience gathered around, the pickpockets went to work.

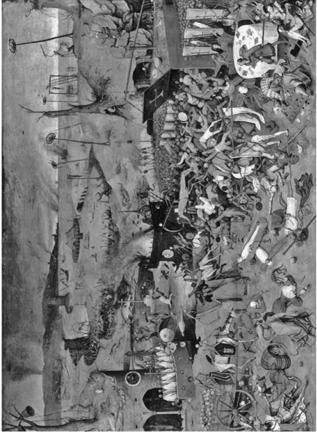

Pieter Brueghel the Elder, 1562.

Triumph of Death. A dying man plays the lute as Death fiddles. Skeletons ring

bells from a dead tree, emaciated figures (representing death) drive a horse

and wagon filled with skulls. A crow sits on the horse looking down on the

dying and the dead.

THE PLAGUE

The bubonic plague appeared about every five years as a

regular part of daily life; nobody knew where it came from. About all they

could do was pray to God that it would not descend upon them. Many people

scraped bits of sandstone off the local churches, placed them in a bag that

they wore around the neck as a kind of holy talisman against the disease, which

was blamed on many things such as eating apples and plums, mosquitoes, the

dirty water of the canals, foreigners, or the Jews who were often rounded up

and exiled. Everyone had an opinion as people died by the thousands.

The Catholic Church’s view, however, generally prevailed.

The priests maintained the plague came because of the sins of man and was a

sign of the wrath of God. Hygiene was generally very poor, however. People wore

the same shirt for weeks on end both day and night, a haven for fleas. No one

made the connection between plague, rats, and fleas. Rats carried fleas that,

in turn, carried the disease. Nearly everyone had fleas in their clothes and in

their beds. Pitch was burned in barrels in the streets in attempts to purify

the air.

Calling for the surgeon was generally futile because few

would come, considering it too dangerous. Those doctors who braved the plague

received extra pay for perilous duty. They would perform the usual

bloodletting, check the urine, and cover the boils with a poultice or with a

dried toad. Usually a priest would be in attendance not only to give a

blessing, but also to record the will and testament of the dying person in case

there was something to be given to the Church.

Coffins were at a premium in a plague-ridden area. When an

epidemic struck, corpses filled the streets waiting for burial. Those who had

had money were buried within the Church, creating an almost unbearable stench,

masked by huge amounts of incense. The less well off were buried in the church

yard. To prevent pigs from digging up the bodies, iron grates were laid down.

If the churchyard was filled up, the bodies were taken outside of the city and

dumped into mass graves.

Those who lived in a neighborhood where the plague appeared

generally fled, helping to spread it around. All the while, night and day, the

church bells tolled. The usual sign indicating there was plague in a house was

a bundle of straw hanging from the fac

a

de. Children who had lost a

brother or sister to the disease had to carry a white stick when they played in

the streets. Others played games that involved make-believe funerals in which two

boys carried a third through the streets, lying on a plank, wrapped in a

blanket. A fourth boy led the little parade holding a wooden cross.

OCCUPATIONS

Many household items were sold by itinerant vendors from

door to door. From them the lady of the house could purchase candles, wood,

ceramic or copper candleholders, candle snuffers, and small lamps that burned

rapeseed oil for heat and light. People went to bed early, often just after

dark, hence little artificial light was required.

In 1566, occupations in Antwerp, one of the largest cities

in northern Europe, were recorded:

169 bakers

78 butchers

91 fishmongers

110 barber-surgeons

124 goldsmiths

300 painters and sculptors

594 tailors and stocking makers

There were, to be sure, some doctors of medicine, numerous

clerics and monks, musicians, and actors, traders, and many thousands of

laborers, sailors and foreign merchants, and beggars.

Most women were able to spin and make a little extra

income, which they did at home. Using wool or flax, they fastened the fibers to

a wooden distaff. The fibers were pulled out with one hand, twisted into thread

with the other hand, and rolled onto a spindle. Eye glasses were available for

those with poor sight.

People who worked for a daily wage lived on the edge. One

month, they had a job; the next month, they had nothing. This was especially

true of farm seasonal workers when the planting or harvesting were finished.

Unable to buy food, they might find a charitable organization in a large city

to keep them from death’s door, and if not, their only alternative was to beg.

Even for nonresidents, the possibility of working as a wage laborer was not

uncommon in the seven northern provinces of the Netherlands. Expected to work

12 to 14 hours a day, they were not usually allowed to reside in the same

village as their employers and lived in squalor in separate dependent villages.

FISHING

The Dutch designed special ships for the Baltic herring

trade, but an edict from Charles V issued in 1519 specified that all ships had

to have a license to sail and that only new barrels could be used. Inspectors

were appointed to verify proper barreling of fish in all ports. Fishing was at

its peak there around 1600–1630, and the many herring factories employed large

numbers of men and women.

The Dutch fishing industry, an important part of the

economic base of the northern Netherlands, included a type of factory ship

called the herring bus that enabled the fishermen to follow the herring to the

shoals of the Dogger Bank and other places, far from the shores of the

Netherlands, and to stay at sea for long periods. This ship was equipped to

salt the fish while at sea. Herring was an important export.

Fishing also attracted its own supporting businesses such

as trade in and refining of salt, manufacturing of fishnets, and specialized

building of ships. Traders invested the fishing revenues in buying up grain in

Baltic ports during the winter months that they transported to Western Europe

when the ice floes thawed in spring. The income generated from this incidental

trade was invested in unrefined salt or in new ships. The fishing fleet was

protected by naval vessels against privateers.

TRAVEL AND TRANSPORTATION

With no reliable transportation service available, there

was little possibility of sending packages or goods to another party or to

another city. Instead, people carried their own belongings from place to place

in sacks or baskets usually conveyed on their heads or backs or by use of a

yoke. Wheelbarrows could be converted into sleighs in winter for traveling over

frozen rivers or canals. Rowboats and sailboats were plentiful in summer and

were used to carry passengers and their luggage from one side of a river or bay

to the other; they were also used to transport grain from region to region

around the Baltic Sea.

Horses were a primary means of transport, but sometimes

three or four peasants shared one since not everyone could afford a horse.