Read Daily Life During The Reformation Online

Authors: James M. Anderson

Daily Life During The Reformation (26 page)

THEATER

Mystery plays, that is, medieval religious dramas based on

the Bible, continued to be performed during the Renaissance and Reformation in

public squares, chateaux, upper class homes, and in some abbeys throughout

Europe. Comedies, farces, ballets, and reproductions of Greek and Roman

classics became more popular. In France, the upper classes sat in the boxes

overlooking the galleries often paying nothing. They imperiously announced

their name and went to their box. Their servants did the same. Below sat or stood

the commoners, workers, pages, clerks, and thieves. These people came to the

theater around noon although the performance did not begin until two o’clock.

They fought over seats and often turned the place into a rowdy brawl before the

play began. Playwrights were careful about what they wrote: a satire on a

prominent figure or the Church might delight the crowd but land the author in

jail.

The nature of stage plays began to change during the

Reformation. Instead of depicting stories of heroines who preferred death to

losing their virginity, dramas concentrated more on the benefits of marriage

and family life. The medieval passion plays, the dramatic presentation

depicting the trial, suffering, and death of Jesus and the resurrection,

continued to be performed at Easter, but other mystery plays dedicated to

miracles, the flood, and other biblical stories that were sometimes staged by

the various guilds, waned in popularity in Protestant areas.

Felix Platter’s memoirs mention theatrical productions in

Switzerland. In Basel, attending was free of charge, and the plays were

performed in venues such as the fish and grain markets and at the university

gymnasium. Their subject matter included religious themes taken from both the

New and Old Testament, such as the conversion of St. Paul and Christ’s

Resurrection, as well as the “Ten Ages of Man” about European culture, and a

play entitled “Hamanus” that propagated Lutheran beliefs. In Basel, Latin

comedies by Plautus and Terence were also staged.

In England, actors were regarded with suspicion by the

authorities who considered them worthless. After 1572, actors had to have a

license. Plays were generally put on in market squares. In 1576, the first

theater was built by James Burbage. Those who could afford the best seats were

shielded from the weather, but most stood in the open air. Boys played women’s

parts, and there were no female actors.

Elizabeth I was a patron of arts and literature and loved

watching plays, masques, and other dramatic performances. She had her own

company of actors, The Queen’s Players, who often performed for her and her

courtiers.

ENGLAND

There was much literary activity at this time with writers

such as Shakespeare, John Milton, and John Bunyan. After the advent of printing

in 1476, books became cheaper and reading popular among the educated.

Elizabeth I also enjoyed hawking and hunting and would hunt

deer and stags with her courtiers, and when the unfortunate animal was caught,

she would be invited to cut its throat. In 1575, the French Ambassador reported

that she had killed “six does” with her crossbow. The queen and her courtiers

would often have a picnic in the forest while hunting.

Like the rest of Europe, the Elizabethans had no concept of

animal cruelty, and enjoyed a whole manner of violent animal “sports,” such as

bear-baiting (where dogs were trained to attack a bear chained to a post),

cock-fighting, and dog-fighting.

The queen also enjoyed watching a game of tennis,

especially if one of her favorite courtiers was playing. Once she even dressed

up as one of her ladies so that she could secretly watch Robert Dudley compete

in a shooting match, and afterward, she surprised him by revealing her

identity.

Elizabeth had a love of learning and reputedly studied two

or three hours a day. She read books in Latin or French and translated classic

works into English. She also wrote poetry, and a few of her poems are still

extant. Embroidery was a popular pastime for women, and the queen sometimes

spent an evening embroidering with her maids of honor and ladies in waiting.

There were also games they could play on rainy days or winter nights, among

them backgammon, chess, and cards. Darts was also enjoyed by the nobility.

Christmas, an elaborate occasion in England, was celebrated

with strong ale, feasting, and a carnival atmosphere. In poorer houses, games

such as shoe-the-mare were played, in which a girl was chased around the house

by those attempting to shoe her. Some young men played a version of football

with few rules. Goal posts were set far apart, and the field often included

woods and streams. Injuries were common.

Holidays

The holiday period extended to the twelfth night after

Christmas, a time when lord, lady, servants, and workers mingled freely as

equals in the same halls and took part in the same games. The poor visited the

great houses and begged for ale, which was freely given. A huge yule log was

dragged into the house and set alight in the fireplace to ward off evil

spirits, mingling its light with the many candles on the sideboards. As the log

burned, family, friends, and domestics consumed quantities of yule dough, cake,

and boiled wheat in milk flavored with sugar, spice, and raisins. After

Christmas, dancing, masked balls, bowling, and children’s games carried on the

festivities. Among poor houses, plays were performed by door-to-door troupes of

traveling actors and musicians.

New Year’s Eve was celebrated by feasting and drinking one

another’s health, and New Year’s Day was celebrated by an exchange of gifts in

the home. In cities people went to neighbors’ houses at midnight to wish them

good cheer.

Other feast days with quantities of food for the wealthy

were Easter, followed by May Day when flowers were gathered, queens elected

from the common people, and maypoles erected bedecked with flowers. Young women

gathered morning dew to apply to their faces as a charm to protect them from

blight. People came out dressed in their best, performed Morris dances, and

took part in pantomimes.

Other Celebrations

In the tradition of the old pagan rites, June was the month

when Midsummer’s Eve was celebrated. Fires were lit at midnight in the cities

and on the hilltops to commemorate the passing of the sun god through the

highest point of the zodiac, summer solstice; and parades, merrymaking, and

pageants abounded. Pickpockets were also out in force as were the police to

maintain order. Queen Elizabeth helped to temporarily relieve the unemployment

problem by hiring workers to build the wagons for the parades, to construct

stages and stands, to collect wood for the bonfires, and later, to clean up the

streets of the city.

The harvest was celebrated on September 29, Michaelmas Day,

and the family who could afford it satisfied their appetites with a sumptuous

dinner of roasted goose, cakes, and puddings. On the eve of November 1, All

Saints (Halloween), outdoor fires were kindled; and drinking and dancing went

on through the night. It was believed that this was the night when witches and

goblins came to do their mischief.

November 11 was Saint Martin’s day when the goose was again

the centerpiece of the bountiful table; and this was followed by Saint

Catherine’s feast, a day of rejoicing along with a good deal of cider as it

coincided with the apple harvest.

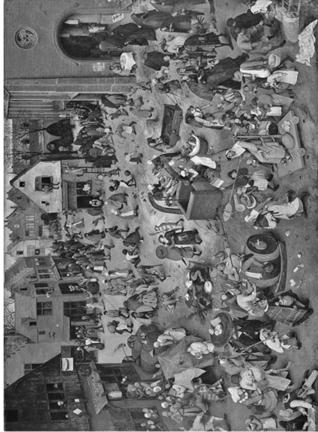

The Fight between Carnival and

Lent, Pieter Brueghel the Elder, 1559. The painting shows the contrast between

enjoyment and drinking (the Inn, left) and of serious religious observance

(church, right). Carnival is represented by the fat man on a barrel, with a pie

on his head and with a pig’s head on a spit.

CARNIVAL

The annual carnival in most southern cities of Europe held

just before Lent was the most important of the popular festivals. Men, women,

youths, and sometimes even priests, put on masks concealing their identity and cavorted

around the towns. They played tricks on one another, made a lot of noise, and

mocked the municipal officials and even church rituals. This was the time to

forget the restraints of daily life. Floats drawn through the streets in

procession often featured giants of gargantuan proportions or awe-inspiring

figures such as bears, dragons, and a variety of farmyard animals. Participants

enacted pantomimes on street corners or on the floats. For example, a man

acting the part of Noah’s wife made it clear that she, not Noah, was in charge

of the ark. Plays were staged suggesting the rich and powerful were incompetent

fools. Magistrates were ridiculed for their decisions and lust for money.

People of high position might be shown as asses. Authorities, subjects of

farces, were expected to laugh at themselves, and perhaps better serve the

community in the future.

Anti-Catholic incidents were common in many German-speaking

cities during Carnival. Effigies of the pope, cardinals, and bishops were

especially ridiculed with such things as the devil’s horns and tails.

Interaction between social events such as carnival and Reformation was evident

in Wittenberg on December 10, 1520. That morning at the university Luther had

burned the papal bull condemning him, and in the afternoon about 100 students

staged a carnival. A float was prepared full of young men with mock papal bulls

stuck on the end of sticks or on swords.

Accompanied by music, they boisterously passed through the

streets drawing laughter from the crowds. They carried books by Luther’s

enemies such as Eck, gathered wood in the city, rekindled the fire where Luther

had burned the papal bull, and burned the books. One dressed like the pope

threw his tiara into the fire.

In some carnivals men dressed as monks pulled plows through

the streets; and women, imitating nuns, walked behind carrying babies. Certain

towns prohibited satirizing the pope; others supported it. Mock hunts of monks,

nuns, priests, and the pope delighted the citizens, sometimes ending with all

trapped in a net.

MUSIC AND DANCING

Music

Music was popular in England during Elizabethan times, and

songs were often accompanied by an eight-stringed lute. On formal occasions,

madrigals were sung that entailed several voices and guests were invited to

join in. Church and instrumental music continued to be enjoyed and after 1560,

Puritans sang psalms in their homes sometimes accompanied by an instrument. It

was not uncommon for a servant with a good voice to sing for the family.

Many villages had their own choir and bell-ringers, and the

royal court made use of high-quality choirs for the pleasure of guests or the

family. Sometimes, young boys with fine voices were taken from their homes and

forced into a choir.

Families liked to show off their daughters’ accomplishments

by having them play the virginal or harpsichord for guests. Both instruments

were household treasures and would often be highly decorated with paintings.

Musical instruments were also used as decorations in the home. A wealthy family

might display cornets, flutes, viols, violins, recorders, and even an organ to

impress company.

Dancing provided pleasure, and variations were many. The

upper classes danced the slow pavan; the faster galliard, which entailed

leaping into the air in time with the music; and the volta in which the woman

was lifted high above the floor. Lively dances also were the coranto (or

courante) and the Spanish canary. Morris dancing, a type of group folk dancing,

was popular with all levels of society.

Elizabethans loved music, and the queen was no exception.

She played the virginals and the lute, enjoyed musical entertainment,

encouraged musicians and composers, and was especially fond of dancing. She

danced the difficult and demanding galliard every morning to keep herself fit.

She also loved to dance with her courtiers and was fond of the volta.

Wandering musicians were looked down upon by upper class

patrons; but if they were good, they might on occasion play for royalty. It was

customary in taverns to demand music with the meal. The best inns had a lute, a

bandore, and sometimes the virginal to soothe and entertain the guests.