Darwin's Dangerous Idea (51 page)

Read Darwin's Dangerous Idea Online

Authors: Daniel C. Dennett

misstep happens, right before your eyes.)

of San Marco.

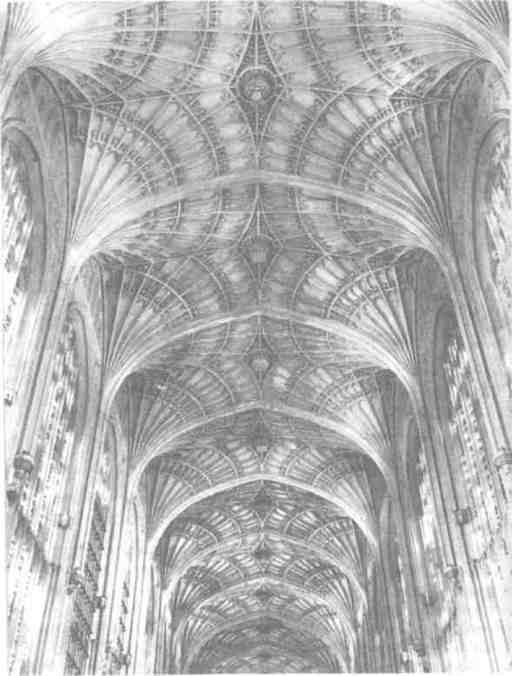

The great dome of St Mark's Cathedral in Venice presents in its mosaic mid-line of the vault, where the sides of the fans intersect between the design a detailed iconography expressing the mainstays of Christian faith.

pillars (figure (10.]2). Since the spaces must exist, they are often used for Three circles of figures radiate out from a central image of Christ: angels, ingenious ornamental effect. In King's College Chapel in Cambridge, for disciples, and virtues. Each circle is divided into quadrants, even though example, the spaces contain bosses alternately embellished with the Tudor the dome itself is radially symmetrical in structure. Each quadrant meets rose and portcullis. In a sense, this design represents an 'adaptation', but one of the four spandrels in the arches below the dome. Spandrels—the the architectural constraint is clearly primary. The spaces arise as a nec-tapering triangular spaces formed by the intersection of two rounded essary by-product of fan vaulting; their appropriate use is a secondary arches at right angle (figure [10.]1)—are necessary architectural by-effect. Anyone who tried to argue that the structure exists because the products of mounting a dome on rounded arches. Each spandrel contains alternation of rose and portcullis makes so much sense in a Tudor chapel a design admirably fitted into its tapering space __ The design is so elab would be inviting the same ridicule that Voltaire heaped on Dr Pangloss....

orate, harmonious and purposeful that we are tempted to view it as the Yet evolutionary biologists, in their tendency to focus exclusively on im-starting point of any analysis, as the cause in some sense of the surrounding mediate adaptation to local conditions, do tend to ignore architectural architecture. But this would invert the proper path of analysis. The system constraints and perform just such an inversion of explanation. [Gould begins with an architectural constraint: the necessary four spandrels and 1993a, pp. 147-49.]

their tapering triangular form. They provide a space in which the mosa-icists worked; they set the quadripartite symmetry of the dome above....

First, we should notice that from the outset Gould and Lewontin invite us Every fan vaulted ceiling must have a series of open spaces along the to

contrast

adaptationism with a concern for architectural "necessity" or

270 BULLY FOR BRONTOSAURUS

The Spandrel's Thumb

271

should

expand

our reverse-engineering perspective back onto the processes of R and D, and embryological development, instead of focusing "exclusively on

immediate

adaptation to

local

conditions." That, after all, is one of the main lessons of the last two chapters, and Gould and Lewontin could share the credit for drawing it to the attention of evolutionists. But almost everything else that Gould and Lewontin have said militates against this interpretation; they mean to oppose adaptationism, not enlarge it. They call for a "pluralism" in evolutionary biology of which adaptationism is to be just one element, its influence diminished by the other elements, if not utterly suppressed.

The spandrels of San Marco, we are told, "are necessary architectural byproducts of mounting a dome on rounded arches." In what sense necessary?

The standard assumption among biologists I have asked is that this is somehow a

geometric

necessity, and hence has nothing whatever to do with adaptationist cost-benefit calculations, since there is simply no choice to be made! As Gould and Lewontin (p. 161) put it, "Spandrels must exist once a blueprint specifies that a dome shall rest on rounded arches." But is that true?

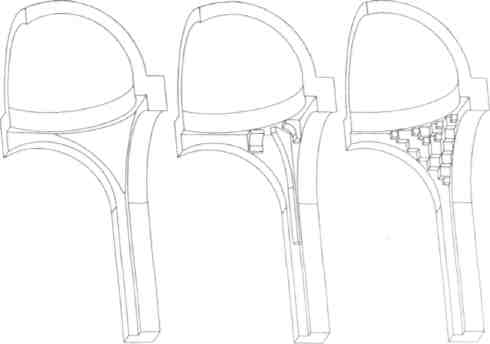

It might appear at first as if there were no alternatives to smooth, tapering triangular surfaces in between the dome and the four rounded arches, but there are in fact indefinitely many ways that those spaces could be filled with masonry, all of them about equal in structural soundness and ease of building. Here is the San Marco scheme (on the left) and two variations. The variations are both, in a word, ugly (I deliberately made them so), but that does not make them

impossible.

Here there is a terminological confusion that seriously impedes discus-FIGURE 10.2. The ceiling of King's

College Chapel.

"constraint"—as if the discovery of such constraints weren't an integral part of (good) adaptationist reasoning, as I have argued in the last two chapters.

Now, perhaps we should stop right here and consider the possibility that Gould and Lewontin have been massively misunderstood, thanks to the misfiring rhetoric of this opening passage, rhetoric which they even correct somewhat, in the last sentence quoted above. Perhaps what Gould and Lewontin showed, in 1979, is that we must all be

better

adaptationists; we FlGURE 10.3

272 BULLY FOR BRONTOSAURUS

The Spandrel's Thumb

273

sion. Does figure 10.3 display three different sorts of spandrels, or does it display a spandrel on the left, and two ugly alternatives to spandrels? Like other specialists, art historians often indulge in both strict and loose usages for their terms. Strictly speaking, the tapering, roughly spherical surface illustrated in figure 10.1, the sort of surface illustrated on the left in figure 10.3, is called a

pendentive,

not a

spandrel.

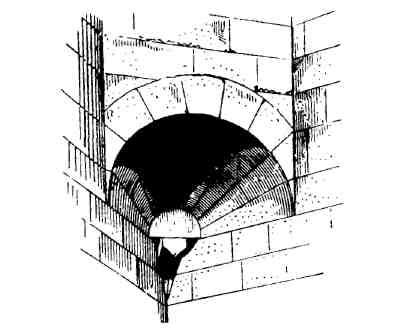

Strictly speaking, spandrels are what remains of a wall once you punch an arch through it, as in figure 10.4.

(But even that definition leaves room for confusion. In figure 10.4, are we shown spandrels on the left, and something else on the right, or do "pierced spandrels" count as spandrels, strictly speaking? I don't know.) Speaking more loosely, spandrels are places-to-be-dealt-with, and in that looser sense, the three variations in figure 10.3 all count as spandrel varieties.

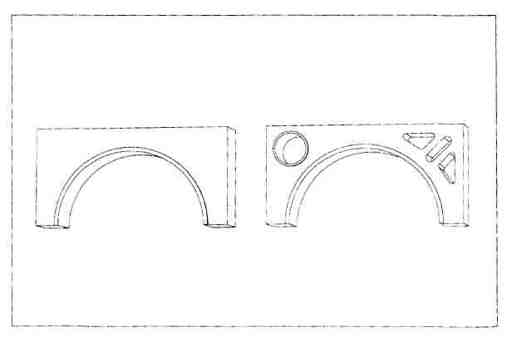

Another variety of spandrel (in that sense ) would be a

squinch,

shown in figure 10.5.

But sometimes art historians speak of spandrels when they are talking specifically about pendentives, the variety shown on the left in figure 10.3. In

Squinch.

A corbelling, usually a small arch or half-comical niche, which is placed that sense, squinches are not types of spandrels, but rivals to spandrels.

across the corners of a square bay in order to form an octagon suitable for carrying Now, why does all this matter? Because, when Gould and Lewontin say an octagonal cloister-vault or a dome. [Krautheimer 1981.]

F

that spandrels are "necessary architectural by-products," what they say is IGURE 10.5

false, if they are using "spandrel" in the narrow sense (synonymous with place a dome over four arches, you have what you might call an

obligatory

"pendentive") and true only if we understand the term in the loose, all-inclusive sense. But in that sense of the term, spandrels are design

problems,

design opportunity-,

you have to put something there to hold up the dome—

not

features

that might either be designed (adaptations) or not. Spandrels in some shape or other, you decide which. But if we interpret spandrels as the loose sense are indeed "geometrically necessary" in one regard: if you obligatory places for one adaptation or another, they are hardly a challenge to adaptationism.

But is there nevertheless some other way in which spandrels in the narrow sense—pendentives—truly are nonoptional features of San Marco? That is what Gould and Lewontin seem to be asserting, but if so, they are wrong. Not only were the pendentives just one among many

imaginable

options; they were just one among the readily

available

options. Squinches had been a well-known solution to the problem of a dome over arches in Byzantine architecture since about the seventh century.'

What the actual design of the San Marco spandrels—that is, pendentives—

has going for it are mainly two things. First, it is (approximately) the

"minimal-energy" surface (what you would get if you stretched a soap film in a wire model of the corner), and hence it is close to the minimal surface area (and hence might well be viewed as the optimal solution if, say, the number of costly mosaic tiles was to be minimized!). Second, this smooth surface is

ideal

for the mounting of mosaic images—and that is why the 1. "Whatever the origin of the dome on squinches, however, the importance of the FIGURE 10.4

question, it seems to me, has been vastly overplayed. Squinches are an element of construction which can be incorporated into almost any kind of architecture." (Krautheimer 1981, p. 359.)

274 BULLY FOR BRONTOSAORUS

The Spandrel's Thumb

275

Basilica of San Marco was built: to provide a showcase for mosaic images.

after all.2 That is curious, you may think, but not theoretically important, The conclusion is inescapable: the spandrels of San Marco aren't spandrels because, as Gould himself has often reminded us, one of Darwin's funda-even in Gould's extended sense. They are adaptations, chosen from a set of mental messages is that artifacts get recycled with new functions—"ex-equipossible alternatives for largely aesthetic reasons. They were

designed

to apted," to use Gould and Vrba's coinage (1981). The panda's thumb is not have the shape they have precisely in order to provide suitable surfaces for really a thumb, but it is pretty good at doing what it does. Isn't the Gould-the display of Christian iconography.

Lewontin concept of a spandrel a valuable tool in evolutionary thinking even After all, San Marco is not a granary; it is a church (but not a cathedral).

if its birth was, to exapt yet another famous phrase, a frozen accident of The primary function of its domes and vaults was never to keep out the rain—

history? Well, what

is

the function of the term "spandrel" in evolutionary there were less expensive ways of doing that in the eleventh century, when thinking? So far as I know, Gould has never given the term (in application to these domes were built—but to provide a showcase for symbols of the creed.

biology) an official definition, and since the examples he has relied on to An earlier church on the site had burned and been rebuilt in 976, but exhibit his intended meaning are at best misleading, we are left to our own subsequently the Byzantine style of mosaic decoration had provoked the devices: we should try to find the best, most charitable, interpretation of his admiration of powerful Venetians who wanted to create a local example. Otto texts. When we turn to that task, one point emerges from context with clarity: Demus (1984), the great authority on the San Marco mosaics, shows in four whatever a spandrel is, it is supposed to be a non-adaptation.