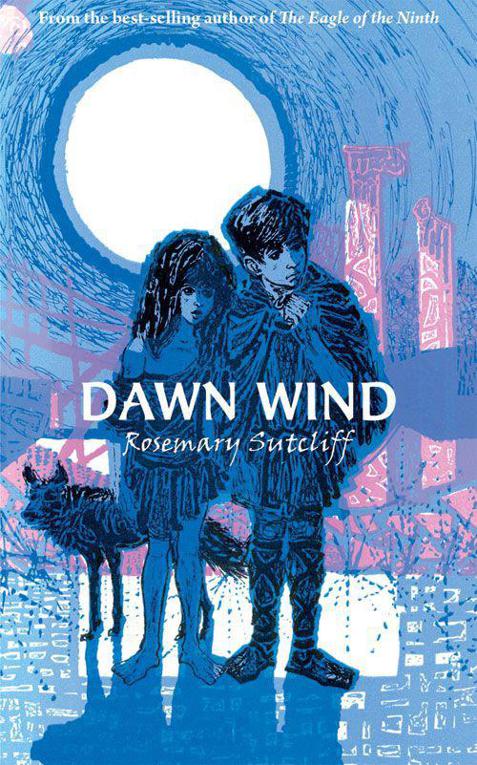

Dawn Wind

Authors: Rosemary Sutcliff

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Copyright (c) Anthony Lawton 1961

The moral rights of the author and illustrator have been asserted

Database right Oxford University Press (maker)

First published 1961

First published in this eBook edition 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

ISBN: 978-0-19-279360-7

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Cover and inside illustrations by Charles Keeping

13

T

HE

W

RECK

18

V

ADIR

21

D

AWN

W

IND

The Breaking of Britain

T

HE

moon drifted clear of a long bank of cloud, and the cool slippery light hung for a moment on the crest of the high ground, and then spilled down the gentle bush-grown slope to the river. Between the darkness under the banks the water which had been leaden grey woke into moving ripple-patterns, and a crinkled skin of silver light marked where the paved ford carried across the road from Corinium to Aquae Sulis. Somewhere among the matted islands of rushes and water-crowfoot, a moorhen cucked and was still. On the high ground in the loop of the river nothing moved at all, save the little wind that ran shivering through the hawthorn bushes.

For a long while that was all, and then in the dark heart of the hawthorn tangle something rustled that was not the wind. It stirred, and was still, and then stirred again with a kind of whimpering gasp, dragging itself forward little by little out of the black shadows among the thorn roots, like a wounded animal. But it was no animal that crawled painfully into the moonlight at last, it was a boy. A boy of fourteen or so, with a smear of blood showing dark on his forehead, and the same darkness clotted round the edges of the jagged rent in his leather sleeve.

He propped himself on his left arm, his head hanging low between his shoulders; and then, as though with an intolerable effort, forced it upward and looked about him. Westward along the high ground the ring of ancient earthworks where the British had made their last night’s camp stood mute and deserted now, empty of meaning as an unstrung harp, against the ragged sky. Far down the shallow valley, the camp-fires of the Saxons flowered red in the darkness, and between the dead camp and the living one, all along the river bank and over the high ground and along the line of the road to Aquae Sulis, stretched an appalling stillness scattered with the grotesque, twisted bodies of men and horses.

Only a few hours ago, all that stretch of stillness had been a thundering battle-ground, and on that battle-ground, the boy’s world had died.

One of the tumbled bodies lay quite close to him, with arms flung wide and bearded face turned up to the moon. The boy knew who it had belonged to—rather a comic old man he had been when he was alive, always indignant about something, and his grey beard had wagged up and down when he talked. But now his beard did not wag any more, only it stirred a little in the night wind. Beyond him another man lay on his face with his head on his arm as though he slept; and beyond him again lay a tangle of three or four. Last night they had told stories of Artos and his heroes round the camp-fires. But Artos was dead, almost a hundred years ago, and now they were dead too. They had died at sunset, under a flaming sky, with all that was left of free Britain behind them, and their faces to the Saxon hordes. It was all over; nothing left now but the dark.

The boy’s head sank lower, and he saw a hand spread-fingered on the ground before him. The fingers contracted as he watched, and he saw them dig deeper into the moss and last year’s leaves, as though they had nothing to do with him at all. But the chill of the moss was driven under his own nails, and he realized that the hand was his, and understood in the same moment that he was not dead.

For a little, that puzzled him. Then he began to remember, and having begun to remember he could not stop. He remembered the brave gleam of Kyndylan’s great standard in the sunset light, and the last stand of the fighting men close-rallied beneath it. His father and Ossian and the rest, the desperate, dwindling band still holding out, long after those that gathered to Conmail of Glevum and Farinmail of Aquae Sulis had gone down to the last man. He remembered the inward thrust of the Saxons yelling all about them, and the sing-song snarling of Kyndylan’s war-hounds as they sprang for Saxon throats. He remembered struggling to keep near his father in the reeling press, and the hollow ringing peal of the war-horns over all. He remembered the glaring face and boar-crested helmet of a Barbarian warrior blotting out the sky, and the spear-blade that whistled in over his shield rim even as he sprang sideways with his own dirk flashing up, and the shock of the blow landing just below his sword-arm’s shoulder. Everything had gone unreal and strange, as though the whole world was draining away from him, and suddenly he had been down among the trampling feet of the war-hosts. A heel, Saxon or British, it made no odds, had struck him on the head, and everything had begun to darken. He remembered dimly a gap opening as the battle reeled and roared above him, and crawling forward with a blind instinct to get clear of the trampling feet, and then nothing more. How he came to be where he was, he did not know. Maybe the slope of the hillside had taken him. And in the turmoil and the fading light among the hawthorn scrub, the battle must have passed him by.