Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident (27 page)

Read Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident Online

Authors: Donnie Eichar

THROUGHOUT MARCH AND APRIL THE SEARCH CONTINUES

in the mountains for the remaining hikers—Lyuda Dubinina, Sasha Zolotaryov, Alexander Kolevatov and Kolya Thibault-Brignoles. The radiograms from this period reveal that the searchers concentrated their efforts on an ever-widening radius beyond the cedar tree where the first bodies had been found. By the end of April, the search effort has been operating for more than two months, and signs of wear are showing in the volunteers. There are repeated radiograms sent to Ivdel requesting the usual mood-elevating provisions of coffee and cigarettes. But these are meager comforts in the face of daily battles with lashing winds, deep snow and no hope for a happy ending. In early March, one volunteer slips off his skis and onto an exposed rock, resulting in a knee injury that swells over the next few days. When his condition worsens, he is evacuated by helicopter. But the snow is so deep on the pass that the volunteers have to throw one hundred buckets of water onto the snow to create a helipad.

On May 3, the Mansi searcher Stepan Kurikov comes across some unusual branches just under the snow in a ravine near the cedar tree. The branches appear to have been cut by a knife. Colonel Georgy Ortyukov, who is by that point overseeing the search operations, orders immediate probing of the area surrounding the branches.

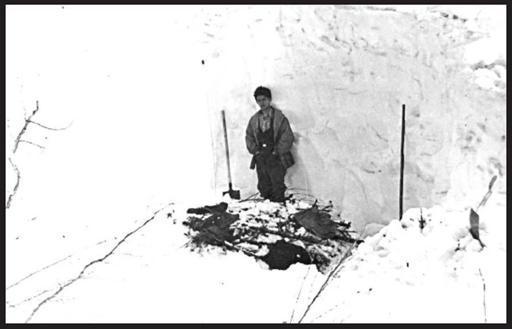

On the first day of probing, about six yards away from the branches, a volunteer discovers a piece of clothing at the end of his metal probe. With shovels, he and his team dig a large hole above the creek bed, a cavity that will eventually reach a depth of 8 feet and an area of 100 square feet. The digging proceeds in fits and starts until the volunteers hit upon something solid. Realizing it is only a tree trunk, they move to a different spot and begin again.

Later that day, they hit upon a cache of clothing. What is odd about the articles is that they are abandoned in the snow, not attached to a person. Stranger still, some of the clothing looks to have been cut or shredded. There is a crumpled gray Chinese woolen vest turned inside out, knitted trousers, a brown woolen sweater with lilac thread, a right trouser leg and a bandage one yard long. The more Ortyukov and his men dig, the closer they come to the creek bed, which means, by the second day, that the men are digging through a combination of snow and slush. The second day of excavation reveals yet more clothing: black cotton sports trousers with the right leg missing—presumably the other half from the previous day’s trousers—and half of a woman’s sweater, belonging to Dubinina.

On the second evening, the men’s shovels hit upon a body. It is clearly a man, though the decomposition from the water is such that the face is unrecognizable. He is wearing a gray sweater and, strangely, two wristwatches. The men continue to dig, soon uncovering three more bodies lying nearby. Lyuda’s is the only identifiable one of the four. She is dressed in a cap, a yellow undershirt, two sweaters, brown ski trousers and two socks on one foot. The other foot is wrapped in a torn sweater. Her head is pointed upstream, while the three men are oriented toward the center of the stream. Two of the men are found in a position of embrace, in what appears to be a desperate attempt to conserve warmth.

When Lev Ivanov hears of the discovery, he flies to the mountains to assess the condition of the bodies, arriving on either May 5 or 6. The bodies, which have been lying in a soup of melting snow and creek water, are at various stages of decay. The volunteers have pulled them out of the slush at the bottom of the pit and have wrapped them in a tarpaulin to slow further decomposition. Ivanov notes that the body parts that have managed to avoid the water are mostly intact, but the flesh that was lying in the direct stream of melting snow has succumbed to the water’s microbes. The bodies need to be flown to Ivdel without delay, but the helicopter Ivanov himself flew in on has since left the area. Ivanov sends a radiogram to Ivdel stressing the urgency of the situation:

Volunteer Boris Suvorov stands with the hikers’ clothing and a bed of twigs found beneath the snow, May 3, 1959.

The bodies of the last of the four hikers are pulled from a ravine, May 5, 1959. Colonel Georgy Ortyukov is pictured in the middle of frame with striped hat.

IF THEY ARE NOT EVACUATED TOMORROW THEY’LL DECOMPOSE.

Burying the bodies on the spot is out of the question, of course, and not just because their families will be robbed of a respectable burial. The last four hikers are the missing link in the story of what happened on the night of February 1. If their bodies are not immediately transported to Ivdel for a proper autopsy, Ivanov knows it will be a disastrous setback from which his investigation may not recover.

24

2012

BY THE TIME I FINISHED MY TOUR OF USHMA, A LIGHT

snow had begun to fall. I returned to the cabin to find my companions still discussing the weather. The consensus seemed to be that a storm was headed our direction, but the group was divided on whether or not one would strike us on the pass. Kuntsevich had, in any case, given his consent for the day’s travel, though with some provisos. First, he was electing to stay behind as a point of contact in the village in case something were to happen to us on our journey. Second, we were to ride snowmobiles most of the way, at least to the Dyatlov incident’s unofficial shrine, Boot Rock. And finally, we would not be camping on Holatchahl mountain, but would instead be returning to the village that night. At the mention of these last two conditions, I started to protest, but Kuntsevich was in no mood for discussion on the subject. It would be foolish in this weather, he insisted, to attempt the entire 45-mile trek along the river on foot, let alone contemplate spending more than one day out there.

But was the weather really any more dangerous than when the hikers had set out in the winter of 1959? Wasn’t that the very point—to set up camp on the slope of Holatchahl, just as they had? Perhaps Kuntsevich was simply trying to save us from spending the night in dangerous, avalanche-prone territory. Snowmobiles, after all, were notorious for disrupting precarious snowdrifts and burying riders who refused to heed the warnings. Why tempt fate

by spending the night beneath unsettled snow? My plans to shadow the hikers’ exact movements were being checked at each turn, but in the chain of command, Kuntsevich had final say.

I was dismayed we wouldn’t be making the trip in the same fashion as the hikers had—with skis strapped to our boots—but once our three snowmobiles had arrived, complete with three drivers, my objections fell away. Having never ridden a snowmobile, I found the entire prospect thrilling, and after climbing on behind my Russian driver, we were off on our terrestrial jet skis. But as we headed northwest from Ushma along the Lozva River, the hazards of our chosen mode of travel became quickly apparent. Driving on the frozen river itself was most efficient, but when the ice cracked beneath us, we quickly maneuvered to the bank. None of us was prepared for the roughness of the terrain: branches flying in our faces, rocks hidden beneath snow, and craters lying in ambush. Just staying on the vehicle required my intense concentration and there was little time to appreciate the landscape or to chat with my companions. The first hour passed without incident, but by the end of the second hour, our drivers had each wiped out more than once. There was an art to wiping out; the moment you sensed the snowmobile was about to tip over, you had to bail before the vehicle landed on top of you or on one of your limbs. I didn’t need to be told more than once that breaking a bone out here would be bad news.

For 40 miles, there was nothing but the hum of the engines and the dark mass of the woods on either side of us. If there was ever an archetypal wood for Russian fairy tales (or nightmares), this was it. Then suddenly, into our sixth hour of travel, the trees stopped, and we entered an endless moonscape of snow. It might well have been the lunar surface if not for the occasional tree—that is, if you can call a dwarf pine that doesn’t extend past one’s knees a tree. We continued on in this nearly featureless topography, and about half an hour later, after we crested a small hill, a mottled black-and-gray shape seemed to rise out of the snow. As we drew closer, I recognized

it as Boot Rock—a formation that did, in fact, resemble a hiking boot, if a severely mistreated one. The 30-foot-high jagged stone seemed an unlikely blemish upon the barren tundra, as if it had either been dropped from above or thrust up by a subterranean force.

It seemed wrong to ride up alongside the landmark, so after stopping at a respectful distance, the drivers turned off the engines and we headed to the rock on foot. For the families and friends of the Dyatlov hikers, and for followers of the case, Boot Rock has become a place of pilgrimage, at least during the warmer months when the rock is more accessible. Boot Rock has earned this sanctified distinction not because the hikers came here themselves, but because the search teams, who found themselves nearly a mile away from base camp, had taken shelter here from the February winds and snowfall. The rock had also served as a temporary grave marker for the bodies of the Dyatlov group, which had been stored here until they could be transported to Ivdel by helicopter.

I looked up to see a metal structure resembling a fez crowning the top of the rock, with a star perched on top of it. The 1959 search party had erected the ornament in order to better see the rock from a distance. On the far side of the rock, about six feet above the ground, we found the bronze plaque commemorating the Dyatlov party. In 1964, five years after the hikers’ burial, Kuntsevich and his brothers had helped conceive of and mount the plaque for a special ceremony. Though Yuri Yudin hadn’t made it to the mountains in 1959, he managed the trek to Boot Rock that summer to observe the five-year anniversary of the tragedy.

Friends, take off your hats

In front of this granite rock.

Guys, we won’t let you go . . .

We keep warming up your souls,

Which are staying forever

In these mountains

. . .