Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident (23 page)

Read Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident Online

Authors: Donnie Eichar

At left: Igor Dyatlov, Nikolay “Kolya” Thibault-Brignoles, and Alexander “Sasha” Zolotaryov as they prepare to leave the labaz shelter site under worsening weather, February 1, 1959.

The remaining photographs taken that day reveal the nine friends struggling through a terrain of increasingly sparse trees and blinding weather. There are no jocular photos left, just a group of serious young people determined to conquer a challenging landscape. Two of the images reveal the group skiing single file into a gray haze.

Sunset would come at 4:58 that day, with twilight at 5:52, but because of the heavy cloud cover, they thought it best to set up camp early to avoid getting caught in the dark. They chose a spot on an east-facing slope, which would allow them to pack up quickly in the morning and head straight up the mountain. It took several hours to set up camp, and the hikers were in the tent by 9:00

PM

, ready for the next day’s climb. But the nine would never see the summit of Otorten. In fact, they would never set foot on the mountain at all. The worst night of their lives lay in front of them, and not one of them would live to see the sun rise.

The skiers advance to the location of their final campsite. This is one of the last shots taken by the Dyatlov group, February 1, 1959.

19

MARCH 1959

INVESTIGATORS IN IVDEL WEREN

’

T ABOUT TO SUBMIT

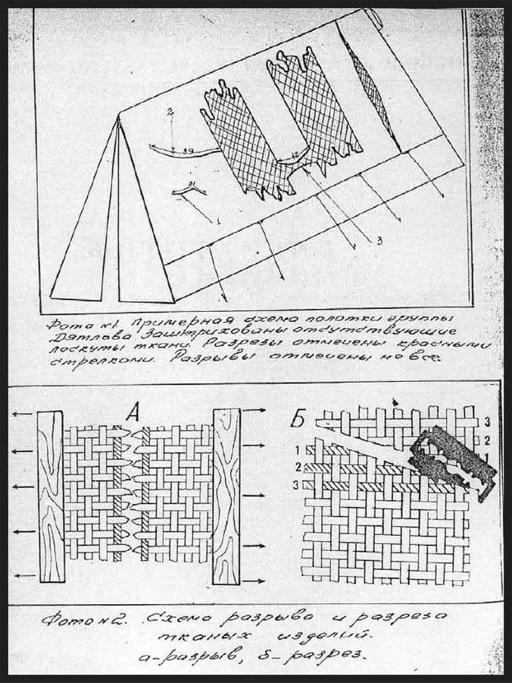

the word of a dressmaker into evidence, but her belief that the cuts to the tent had been intentional prompted another woman, scientific officer and criminal expert G. Churkina, to take a closer look. Disregarding the ice-ax gashes that had been made to the roof of the tent upon its discovery—and the various holes patched by the hikers themselves—Churkina focused on three tears at the back panel opposite the entrance. She was able to quickly confirm that the tears were, in fact, cuts. “Usually a tear spreads along the line of less resistance, i.e., either warp or weft threads are torn,” she wrote in her report. “Such defects are usually very even, with straight angles. A cut always damages both thread types at various angles. It is impossible to cut only warp threads or only weft threads.”

Lev Ivanov and his investigators believed that the case rested on identifying the cause of these gashes, and when the tent had been initially brought in for examination, the condition of the fabric had suggested to some that there had been an outside attacker that night. The determination that the tears had been made by a knife seemed to support this theory, but upon closer examination of the threads under a microscope, Churkina made another discovery: The cuts had come from

inside

the tent. “The defects continue as thin scratches in the corners of the punctures on the internal side of the tent,” she wrote, “not on the external side. Nature and form of damage indicate that the cuts were made from inside by some blade/knife.”

Diagrams from the criminal case files. Top image: “The approximate scheme of the Dyatlov group’s tent. Missing fabric pieces are cross-hatched. Cuts are marked by red arrows. Not all tears are marked.” Bottom image: “Scheme of fabric tear and cut. A) tear, b) cut.”

The Dyatlov hikers’ tent in the prosecutor’s office for examination, 1959.

Once the incisions were determined to have come from the opposite direction, new theories began to emerge. Yuri Blinov, who wrote of the development in his diary, was among those who speculated that the hikers had been caught by surprise by something or someone, and therefore had had no time to completely undo the latches at the entrance. “The tent was cut by a knife from inside in 3 places,” Blinov wrote. “It means that

they

were escaping the tent in panic.”

The forensic examinations of Igor, Zina, Georgy and Doroshenko on March 4, and of Rustik on March 11, would conclude that the five hikers had died from hypothermia. This was an unsurprising conclusion, particularly to those who had found the bodies. The question now was not how they died, but under what circumstances. But if investigators were hoping that the remaining corpses would provide additional clues, they were in for a long wait. Miserable weather, weary volunteers and the March 8 Soviet holiday celebrating International Working Women’s Day slowed search efforts on the slope. In early March, Maslennikov flew to Ivdel to make an appearance in front of the search commission. With the unanimous support of his men, the engineer recommended that search efforts be suspended until April to allow some of the snowpack to melt. The commission, however, rejected Maslennikov’s proposal, opting instead to replace the entire search team and continue as planned.

The commission chose Ural Polytechnic Institute physics professor Abram Kikoin, brother of famed Soviet nuclear physicist Isaak Kikoin, to lead the new team. Kikoin was an avid mountaineer and head of the university’s mountaineering club, which meant he had immediate access to the best volunteers. But once on the

slope, Kikoin and his team encountered the same problems that Maslennikov had. The men battled daily against squall winds, deep snow and myopic visibility, turning up no immediate sign of the remaining four hikers.

During the first week of March, while search efforts were stalling in the mountains, Yuri Yudin took time away from his studies to travel to Ivdel. Because he was one of the few people who knew all nine hikers, he had been summoned by investigators to identify their belongings. It was Ivanov who met Yudin at the Ivdel prosecutor’s office, and it was the investigator’s kindness that helped him get through the distressing process. “He was a good, caring person,” Yudin says of the lead investigator. “He told me, ‘Your conscience is clear—if you were with them, you would have been number ten.’ ”

The searchers on the slope had gathered up the contents of the hikers’ tent haphazardly, having stuffed items into backpacks with little regard to ownership. “Everything was in a giant pile,” Yudin remembers of entering the office. The task of untangling the mass of objects and assigning each one to its proper owner fell entirely on him. It was a solemn procedure, and the head of the UPI physical training department and a reporter from

Na Smenu!

newspaper were both present as witnesses.

One by one, Yudin separated the items into nine piles.

TELESCOPIC TOOTHBRUSH . . . ZINA.

HORN-RIMMED GLASSES IN GRAY CASE . . . IGOR.

BOWIE KNIFE AND COMPASS . . . KOLYA.

MANDOLIN WITH SPARE STRING . . . GEORGY.

GRAY WOOLEN SOCKS RECEIVED AS A PRESENT FROM YUDIN . . . LYUDA.

CHECKED VICUÑA SCARF . . . DOROSHENKO.

HIKING BADGE . . . LYUDA.

ISSUE OF THE SATIRICAL MAGAZINE KROKODIL . . . SASHA.

BLUE MITTENS . . . ZINA.

TEDDY BEAR . . . GEORGY.

Yudin encountered all of the familiar items, but there were surprises too. In Kolevatov’s backpack, along with a broken comb, a grindstone and an aluminum flask, Yudin found a bit of contraband: a pack of flavored cigarettes. It looked as if the cunning Kolevatov had managed to feed his nicotine addiction after all, the no-smoking pledge be damned. And in Igor’s notebook, Yudin discovered a photograph of Zina tucked inside. Had Igor simply been using the snapshot of his friend as a bookmark? Or did this mean something more? It was now, of course, impossible to know. And so it went, until some time later, there lay a diminished pile of clothing and miscellaneous tools to which Yudin was unable to assign an owner.

He left the Ivdel office emotionally spent, but the journey’s heartache was not yet over. On the ride back to Sverdlovsk, he shared a helicopter with a woman who was transporting some of the hikers’ organs to Sverdlovsk. Yudin remembers the ride as deeply unsettling, as he was painfully aware of the grim contents of the nearby containers.

While the organs were being returned to Sverdlovsk for further analysis, the hikers’ families were encountering resistance in getting the bodies of their loved ones returned to them for a proper burial. Now, in addition to wrestling with their own feelings of grief and guilt, the parents of the dead had to contend with the opaque motives of local officials.

Yudin remembers that the regional authorities were eager to get beyond the entire incident, and in private talks with family members, strongly suggested that their loved ones be buried in

the mountains. The officials wanted “for nobody to come to the funeral, for nobody to show up,” Yudin says. “The authorities wanted to bury them where they were found so there would be no funeral and it would be done.”

Rimma Kolevatova, the older sister of Kolevatov, in her testimony to investigators, called the organization of the funeral arrangements “disgraceful.” The search teams had not yet found her brother, but she was keenly aware of the ordeal the other families had endured. The parents of the hikers, she recalled, had been summoned by Party officials into private meetings, in which they were told their children should not be returned to Sverdlovsk, but buried instead in Ivdel. “They lived and studied and made friends in Sverdlovsk,” Rimma told investigators. “Why should they be buried in Ivdel?” According to Rimma, in these private meetings, each set of parents had been told that the other parents had already agreed to an Ivdel burial, with a mass grave and single obelisk marker. When the parents of Zina Kolmogorova proposed that all the families should be called together to come to an agreement, the secretary of the institute committee of the regional Communist party made excuses that the families were too spread out to make a single meeting feasible.

“What kind of conspiracy is that?” Kolevatov’s sister asked. “Why should we go through so many hardships . . . in order to have our relatives buried in their native Sverdlovsk? This is a heartless attitude to people suffering such grave loss. Such an offense to mothers and fathers who had lost their children, good and decent people.”