Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident (20 page)

Read Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident Online

Authors: Donnie Eichar

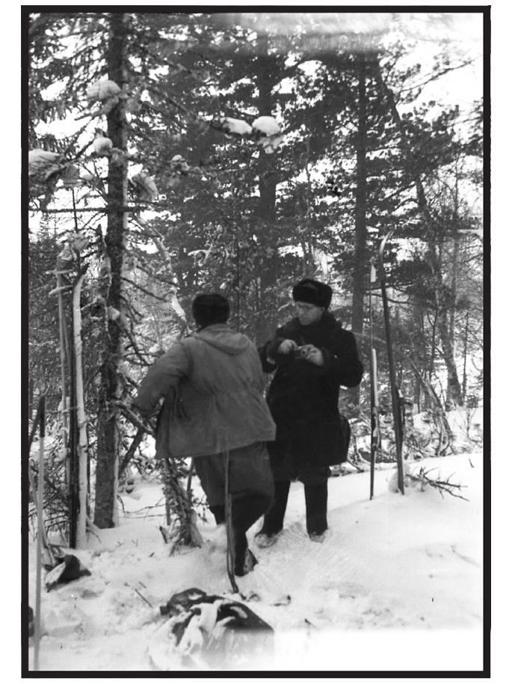

Lev Ivanov on the scene, March 1, 1959.

Together with Maslennikov, Ivanov examines the hikers’ camp and its immediate surroundings. The two men determine that the tent was erected as per hiking regulations. And though the tent is damaged with multiple tears, its integrity on the slope is intact, having clearly been rooted to the slope to account for strong winds.

Maslennikov, in the meantime, in one of his many daily radiograms to Ivdel, begins to imagine a sequence of events for the night of February 1. He suggests that the hikers had dinner in the tent while still in the day’s damp clothes. Then, after nearing the end of dinner, they left the food out as they started changing

into their dry clothes and shoes. At the very moment of changing their clothes, something happened to force all nine hikers out into the snow half-dressed.

MAYBE SOMEONE WHO WAS DRESSED WENT OUTSIDE TO TAKE A LEAK AND WAS SWEPT AWAY. HIS CRY MADE OTHERS JUMP OUT OF THE TENT AND THEY WERE SWEPT OFF TOO. TENT IS SET IN MOST DANGEROUS POINT WITH STRONGEST WIND. IMPOSSIBLE TO GO 50 [METERS] BACK UPHILL AS TENT WAS TORN. THOSE WHO WERE BELOW COULD COMMAND TO GO TO FOREST ON SLOPE TOWARD AUSPIYA WHERE FOREST IS NEAR; MAYBE THEY WANTED TO FIND THEIR PREVIOUS CAMP PLACE. SLOPE IS ROCKY AND 2 TO 3 TIMES FARTHER FROM FOREST. THEY MADE A FIRE. AS DYATLOV AND KOLMOGOROVA WERE BETTER DRESSED, THEY WENT BACK TO LOOK FOR THE TENT WITH THEIR CLOTHES. LACKING STRENGTH THEY FELL.

The weather is challenging for the volunteers on the slope that day, with high winds chafing skin and limiting visibility. By evening, the probing has turned up nothing and the searchers are growing increasingly fatigued. Yuri Blinov, who is taking additional time away from school to continue the search, is among those who craved some levity at the end of a day spent looking for corpses. He wrote of this time in his diary:

In the evenings, participants tired from endless probing of snowy slopes returned to the tent and were telling tales in the absence of other business. Officers were entertaining us with all sorts of stories from criminal world routine. Jokes were popular as well

.

Though he is dedicated to the search for his missing friends, Blinov is exhausted and worried about skipping so many classes. It is time

for him to return to Sverdlovsk. Two days later, Blinov and two other UPI students fly back home to resume their college lives.

The weather on March 2 is little better than the previous day. Probing picks up where it left off, with some of the team expanding its search beyond the river valley. One of Maslennikov’s radiograms that day indicates he is rethinking his initial theory as to the hikers’ fate:

WOULD LIKE TO ASK IF ANY NEW TYPE OF METEOROLOGICAL ROCKET PROBE FLEW OVER INCIDENT PLACE ON THE EVENING OF FEBRUARY 1.

It is a cryptic message, and he doesn’t explain further, adding only:

PLEASE SEND BUTTER, HALVA, CONCENTRATED MILK, SUGAR, COFFEE, TEA, CIGARETTES.

The following day brings a snowstorm and high winds, but the searchers press on, paying particular attention to the Lozva River valley. Maslennikov also expresses for the first time his belief that the rest of the hikers did not get out alive:

TEAM REACHED LOZVA. DYATLOV GROUP’S TRACES NOT FOUND, SNOW FROM MAIN RIDGE DUMPED INTO THIS BROOK, SNOW IS VERY DEEP. PROBABILITY THAT PART OF GROUP ESCAPED THROUGH THIS VALLEY TO LOZVA IS ZERO. . . .

The severity of the storm forces Maslennikov’s group to turn back from the Lozva valley. But another group, which includes Slobtsov and Kurikov, has found the Dyatlov group’s storage shelter near the Auspiya River. There is nothing amiss about the structure. It is built to regulation standards and, aside from the meager amount of firewood, is filled with the necessary food and reserves that

would have been needed for their return trip. The condition of the shelter only reinforces the searchers’ belief that these hikers had stuck religiously to protocol. Among the objects in the shelter is a single sentimental item: Georgy’s mandolin. With this abandoned instrument, the groups’ dedication to their sport is apparent—in earning their advanced hiking grade, even the music they loved was expendable.

Later that day, Maslennikov and his team gather at the improvised helipad to see Lev Ivanov off. The prosecutor has done what he can at the tent site and will continue the investigation from his office in Sverdlovsk. Accompanying Ivanov in the helicopter are the bodies of Doroshenko, Krivonishchenko, Igor Dyatlov and Zina, all of which will undergo autopsies in the next couple of days.

Ivanov may be the lead investigator, but Maslennikov continues to explore his own theories via radiogram:

BUT THE MAIN MYSTERY IS WHY THE WHOLE GROUP FLED THE TENT. THE ONLY THING FOUND OUTSIDE THE TENT BESIDE THE ICE PICK IS A CHINESE TORCH ON THE TENT ROOF. THIS PROVES ONE FULLY DRESSED PERSON WENT OUTSIDE AND GAVE SOME SIGNAL TO OTHERS TO FLEE THE TENT AT ONCE.

Maslennikov also clarifies his question about rocket probes:

ONE POSSIBLE REASON IS SOME NATURAL PHENOMENON OR PASSAGE OF METEOROLOGICAL ROCKET PROBE WHICH WAS SEEN ON FEB. 1 FROM IVDEL AND BY KARELIN’S GROUP ON FEB. 17.

“Karelin’s group” refers to the hiking team led by Vladislav Karelin, who is now among the search volunteers. Karelin and his companions had set out in February, shadowing the Dyatlov group’s path

along the riverbed. At the beginning of the search for the missing hikers, Karelin’s visit to a Mansi village in mid-February, in which he and his fellow hikers shared tea with Pyotr Bahtiyarov, had been mistaken for a visit by Igor Dyatlov’s group. The mistake, which was eventually corrected, only temporarily misled investigators. But the Karelin group’s trip was to become of growing interest in the case. Several days after their visit to the Mansi village, Karelin and his friends had witnessed what he called a “strange celestial phenomenon.” Karelin later told investigators that on the early morning of February 17, he had been awoken by excited cries from the hikers on breakfast duty. “I rushed out of my sleeping bag and tent without boots, just in socks, stood on branches and saw a large light spot,” he recounted. “It grew larger. A small star appeared in its center and also grew bigger. The whole spot moved from northeast to southwest and down.” Karelin said that the light lasted just over a minute, and that he supposed it was a large meteorite. But one of his friends, Georgy Atmanaki, was so terrified by the orb of light, he feared a planet was about to collide with Earth. “I talked with witnesses later,” Atmanaki told investigators, “and they described the event similarly and added that the light was so intense that people were awoken inside their houses.”

Now Maslennikov wonders: Did Igor Dyatlov and his friends witness something similar? Something that caused them to leave the tent wearing no shoes?

Over the coming days, the evidence grows stranger. On March 5, as Karelin and another volunteer are probing a previously unexplored area, about 1,000 yards from the site of the hikers’ tent, they hit something not far beneath the surface: a fifth body. When they dig away the snow, Karelin is able to identify him as Rustik Slobodin. His body is lying facedown with his right leg bent beneath him, and his right fist pulled to his chest. He has on a checkered shirt, sweater, ski trousers, several pairs of socks and a single felt shoe. He also wears a ski cap, which is still intact

on his head—strange, given the prevailing theory that wind blew the hikers from their campsite. Rustik lies midway between where Dyatlov and Zina had been found, their bodies in turn lining up with the site of the tent. Like Zina, Rustik is oriented toward the tent as if he had been working his way up the slope at the time of his collapse. Karelin and his companion notice a small hollow of encrusted snow near Rustik’s nose and mouth, where his breath had melted the surrounding snow, suggesting that Rustik had been alive for some time after he fell. But what is most startling is the front of Rustik’s head, which is deeply discolored, as if he sustained a blunt force to the head.

After pictures are taken and the area thoroughly documented, Rustik’s body is moved to the site of Boot Rock to await transport to Sverdlovsk. And now four hikers remain missing: Lyuda Dubinina, Sasha Zolotaryov, Alexander Kolevatov and Kolya Thibault-Brignoles.

Around this time, after the tent’s contents are transported to Ivdel for further examination, a discovery is made about the tent itself. The discovery had, in fact, been noted in the case file early on, but it was not initially believed to be significant. Besides the ice-ax gashes made by Mikhail Sharavin upon discovery of the tent, there are additional cuts to the back of the tent. These are not the cuts of an ice ax, but appear to be made with more precision. There is one longer cut that is large enough to accommodate a person stepping through it. When a professional tailor is brought to the prosecutor’s office to make a new uniform for one of its officers, the woman is also asked to take a look at the damaged tarpaulin. After examining the threads along the mysterious cut, she confirms what investigators have already concluded: It is a deliberate slash made with a knife. The tailor hesitates to speculate beyond that, but for investigators, the meaning is clear. The hikers themselves would not have damaged their own tent in this way, even by accident, so this seems to suggest one thing: Someone from the outside knifed his way through the tent on that terrible night.

17

2012

WHEN WE ARRIVED AT THE TRAIN STATION, IT WAS STILL

dark. Kuntsevich’s martial discipline had us at the station at eight thirty in the morning, with over an hour to spare. I had been up for three hours, yet was still trying to shake myself out of my medicated daze after having taken a Valium the night before. I was not in the habit of taking pills in order to sleep—the Valium prescription was for my vertigo, a condition I’d been dealing with on and off for the previous seven years. But I had been so wired the previous night that without some help, I wouldn’t have slept at all. Even so, I’d slept only a few hours and was now struggling to stay alert on this first day of our trip.

I left my companions for a moment to explore the station. Fifty-three winters ago, the Dyatlov hikers had nearly missed their evening train leaving from Sverdlovsk. I could almost see them hurrying past me toward the platform, breathless, ten pairs of boots squeaking across the marble floors. I thought of Lyuda’s younger brother, Igor, walking here months later, after having returned from his studies in Uzbekistan. When I’d interviewed him on my last trip, he told me how he’d left Sverdlovsk in the winter of 1959, but because he hadn’t exchanged letters with his family, he had no idea that his sister was missing until he returned that April. He had only to step off the train and see his parents standing there on

the platform to know that something was wrong. Though Lyuda’s body had not yet been found, her fate was written on their faces.

I wanted to imagine that I was occupying the same space as these people I had come to know, but the truth was that this building had been rebuilt and renovated over the years, and must have looked very different in 1959. There was an even older station to the west, a candy-colored artifact of imperial Russia that predated the hikers, which was now a railway museum. This particular station was most recently refurbished in 2003, with many of the old murals having been restored and a few new ones added.

In the vaulted waiting room, I studied the murals on the walls and ceilings, which made plain just how much had changed over the decades. There was a mural of the Romanov family’s celestial ascent, the Red and White armies positioned on either side. I would learn later that this image—featuring the seven Romanovs being pulled skyward, as if by tractor beam—reflected the family’s canonization by the Russian Orthodox Church in the year 2000. What would Yudin, who was still sentimental about Communist Russia, make of it? Even stranger was a mural reminiscent of a Depression-era WPA project. Similar in composition to the Romanov image, it featured two sets of Soviets—scientists on the left and military men on the right. Front and center were the smoking pieces of a plane falling from a blue sky, an American flag visible on a torn wing. Tumbling beside the wing was the plane’s ejected pilot, Gary Powers. Not depicted in the mural was how, instead of injecting himself with the saxitoxin-tipped needle he carried, Powers was instead captured, interrogated for months by the KGB and ultimately convicted of espionage and sentenced to ten years in prison. But less than a year later, the pilot was exchanged in a spy swap for Soviet agent Rudolf Abel. The US government had originally denied the existence of Powers’s aircraft—blaming the incident on a weather plane that had drifted off course into Soviet airspace—only to sheepishly admit

to lying about the whole affair after Khrushchev declared: “I must tell you a secret. When I made my first report, I deliberately did not say that the pilot was alive and well . . . and now just look how many silly things the Americans have said.”