Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident (8 page)

Read Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident Online

Authors: Donnie Eichar

As she told me this, I thought of how Igor’s talent with radios had left followers of the Dyatlov case puzzled. Many couldn’t understand why he had neglected to take a radio with him into the mountains, one he might have used to communicate with rescuers. But shortwave radios of the time were typically over a hundred pounds, and bringing one on a trip wasn’t simply a matter of slipping it into a backpack. In his book

Everything Was Forever, Until It Was No More

, Soviet scholar Alexei Yurchak explains that Soviet policy toward shortwave radios at the time was “ambiguous,” which may explain why young people like Igor were willing to take the risk. The radios may have been officially illegal, but their use wasn’t entirely frowned upon. “Listening to foreign broadcasts was acceptable and even encouraged,” Yurchak writes, “as long as these qualified as good cultural information and not bourgeois or anti-Soviet propaganda.”

Tatiana told me that her brother had been an upstanding Communist and student. When he graduated from high school, he was honored with a silver medal that allowed him to enroll at any university in the country without taking an entrance exam. Part of being a star student, she explained, was adhering to communism like everyone else and believing that education and Party allegiance could elevate the entire country. “One has to remember, a new period of excitement was upon us. Young people wanted to get a higher education, to work in industry; they wanted to find themselves as well as something meaningful to do. The world was opening up around us in 1958, 1959. This was the first time—especially after such a brutal World War and subsequent sanctions and rationing—when people could buy a television or transistor radio.”

But Igor’s greatest passion was not school or even radios—it was the outdoors. He had developed a deep love of hiking over the years, having followed the example of his brother, Slava. “Slava was two years ahead of Igor, and his mentor,” said Tatiana. “But Igor was a real leader and a true sportsman in his own right.”

When I asked Tatiana what her last memory of Igor was, she said abruptly, “He didn’t die from the snow.” She then described seeing the open caskets at the funerals, and how darkly colored and aged their skin had been. “It’s impossible. When people are just freezing and cold, the color of their face is not so dark.” Of her brother’s body, she said, “Igor was twenty-three years old and his hair looked like an old man’s. It was white.” Her family would not have believed it was Igor if not for one distinguishing mark on the corpse, one that brother and sister shared. “We knew it was Igor from the gap in his teeth . . . only the gap.”

She stopped short of speculating what the aged appearance of her brother’s body meant. “It’s too difficult to find the truth. There are too many conflicting stories; so no one, in my opinion, will ever know.”

I asked again what her final memory of her brother was. She told me how they had worked in tandem to develop a photograph he had taken of a mountain, one in the vein of Ansel Adams. “His photos were amazing,” she said softly. She paused again before telling me that their mother had tried to talk Igor out of going on the trip. “My mother said to him, ‘You must not go, you have exams and you need to graduate.’ Igor replied, ‘Mom, this is my last trip.’ . . . For forty years, our mother lived with the fact that her son had died, and that the circumstances of his death were still unsolved, that we might never know the truth.”

When Tatiana began to take things into the kitchen, I sensed our time was up. I would later notice a pattern with my interviews. Everything was friendly until it was suddenly over. Before we said good-bye, Tatiana left me with a final thought: “My mother’s intuition was right. In 1994, before she died, all she remembered was that it was her fault.”

On the train ride back to Kuntsevich’s place, I couldn’t get Dyatlov’s mother out of my head. I wondered how many fretful mothers throughout history had been ignored by their obstinate

children, only to see their nightmares realized. As if the loss weren’t enough, these mothers were sentenced to a life of regret and of hearing the same refrain repeating uselessly in their heads:

I told you so

. With the birth of my own child imminent, the pain of Igor’s mother tugged at my heart.

Igor Dyatlov was beginning to take real shape in my mind as a twentieth-century Renaissance man and adventurer. However, I knew that in order to create a fuller picture of the man and his final days, I would have to go beyond speaking with his sister—who, after all, had been only twelve years old at the time. I would have to talk to Yuri Yudin, the last person to see Igor and his friends alive. I found it difficult to believe that the president of the Dyatlov Foundation hadn’t the slightest idea where the man was. But if Kuntsevich knew Yudin’s whereabouts, he certainly wasn’t telling me.

5

JANUARY 24, 1959

ON THE MORNING AFTER THEIR DEPARTURE, THREE HOURS

before the lazy winter sun had risen, the Dyatlov group disembarked in Serov, an iron and steel manufacturing town 200 miles due north of Sverdlovsk. Blinov and his party joined them on the platform. It wasn’t yet eight o’clock, and after ten and a half hours of gaiety and irregular sleep on the train, both hiking groups were weary. The next train, which was to take them to Ivdel, wasn’t due to depart until evening, leaving the group of friends no choice but to spend the day in this unfamiliar mining town. Perhaps they could visit a local museum or—befitting their academic studies—a metallurgy plant.

Their first instinct was to get some sleep inside the station while it was still dark. They quickly discovered, however, that the doors were locked. The workers inside, speaking brusquely through the station windows, refused to allow any travelers in from the cold.

In classic fashion, Georgy lightened the mood by taking out his mandolin and breaking into song right there on the platform—a conspicuous disruption given the early hour and inhospitable surroundings. In comic imitation of a busker, he set out his felt cap for tips, his beanpole frame and protruding ears adding to the comedy of the moment. But his spontaneous merrymaking didn’t

last long because a nearby policeman heard the noise and strode over. Yudin recorded the incident in the group diary:

A policeman pricked up his ears; the town was all calm, no crime, no disturbances as if it’s communism—and then Yu. Krivo started to sing, he was caught and taken away in no time

.

Without ceremony, Georgy was marched to the police station around the corner. His friends followed and watched as he was scolded by the sergeant.

A sergeant reminded Comrade Krivonishchenko that Article II.3 of Internal Order at railway stations prohibits disturbing other passengers. It’s the first station where songs are illegal, and the first one where we didn’t sing

.

After a stern warning, Georgy was let go, at which point the friends retreated in the opposite direction from the police station, chewing over the details of Georgy’s near arrest as they went. They planned to meet Blinov’s team at the station that evening, which gave them the day to explore the town. Not far down a snow-paved road lined with log-cabin-style houses, the travelers encountered an elementary school, bearing the uninspired name of School #41. Desperate to find a place to catch up on their sleep, they knocked on the front door. A cleaning lady answered and, after hearing their predicament, allowed the group inside. They were soon greeted by a sympathetic schoolmaster, who agreed to let the hikers rest there if, in return, they would speak to his class later that day about their trip. The sleepy friends readily agreed to this new plan.

A typical Soviet school day was broken into two periods: a morning session devoted to proper lessons, followed by a less structured afternoon session, during which pupils could pursue their own activities or gather for guest speakers. Schoolchildren could typically expect war veterans, factory workers, museum docents or writers as afternoon guests. But a group of mountaineers who could regale them with their adventures? This was a rare thing.

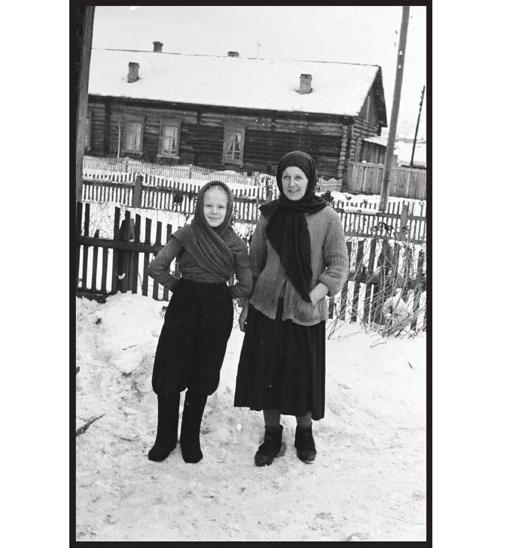

Local villagers in Serov, January 24, 1959.

Alexander “Sasha” Zolotaryov in Serov. Photo taken by the Dyatlov hikers, January 24, 1959.

With Igor and his friends well rested, they piled into a classroom of roughly thirty-five young faces, ranging in age from seven to nine. The little ones were eager to learn, and when the hikers revealed the contents of their backpacks, the children were held in captive fascination. There were ice crackers, maps, Zorki cameras and flashlights—known as “Chinese torches”—passed around the room. The guests even treated the class to a tent-pitching demonstration, and by the end, the children were begging to be taken along on future expeditions. With the educational portion of the visit concluded, the classroom erupted in song. The tattooed Sasha stepped forward with several new songs, including a Russified version of “Mary Had a Little Lamb” by Samuil Marshak. The song gave Sasha and the schoolchildren the opportunity to act out the verse.

Our Mary had a little lamb,

As loyal as a dog,

It always walked with her, yes ma’am,

Through thunder, storm, and fog

.

When it was very, very young

She took it to the steppe,

But now, although it grew its horns,

It still walks in her step

.

Say, Mary walks out of the gate,

The lamb walks after her.

She hops along the street, and what?

The lamb hops after her

.

She reaches a corner, makes a right,

The lamb walks after her.

She shoots ahead with all her might,

It dashes after her

.

While Sasha was certainly the star of the sing-along, the children fell hardest for Zina, and became emotional at the idea of her leaving them. They asked her to be the leader of the “Pioneers”—a youth group similar to the Scouts in the United States—not understanding that Zina couldn’t stay. As evening drew near, the hikers wrapped up their visit with one last song, but the happy conclusion didn’t prevent the children from becoming tearful when the hikers moved to leave. With their teacher’s permission, the entire class poured out of the school and followed the ten adventurers down the road all the way to the train station. The kids pleaded with Zina again, begging her to stay and promising to be well behaved if she would only agree to remain behind and lead their children’s group.

The hikers said their final good-byes to the children and boarded the 6:30

PM

train bound for Ivdel. As they took their seats—and Lyuda prepared to disappear beneath hers—the travelers assumed their adventures in Serov had come to an end. But there was one final incident awaiting them in the train car, a peculiar one given that none of the hikers drank alcohol. Yudin recorded the incident in the group diary:

In the carriage, some young drunkard demanded we give him a half-liter bottle, claiming we’d stolen it from his pocket. That’s the second time today the story ended with interference of a policeman

.