Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident (7 page)

Read Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident Online

Authors: Donnie Eichar

ON THE MORNING OF OUR SECOND DAY IN YEKATERINBURG

, Kuntsevich summoned Jason and me into the downstairs apartment that he and his wife also owned. As we entered, he sat down at a small desk in the main room, surrounded by a giant heap of artifacts and documents on the Dyatlov case. Kuntsevich was wearing the same outfit as the previous day: a pinstriped jacket, mismatched pants, black socks and Russian sandals resembling Crocs. His cell phone, as ever, hung from his neck. After strapping a pair of jeweler’s glasses to his head, he began to tinker with a small steel-framed device that sat on the desk.

Our host seemed to be in no hurry to fill us in on what he was doing—or perhaps he was being willfully obscure—so Jason and I took a seat on the couch and watched him. Finally, Kuntsevich aimed the desktop lamp in such a way that allowed us to get a somewhat better look at the device. It was an olive-green metal box embossed with an alligator pattern, and when I craned my neck I could see a metal device inside that resembled the head of a faucet. There was also some metal twine, and what appeared to be a large baize coaster. With surgical precision, using miniature tools, Kuntsevich toiled away for what must have been forty-five minutes, double-checking each part as if he were conducting a quality check on an assembly line. We were lacking a translator that day, so Jason and I had no choice but to sit there, watching our host work in the lengthening silence. We stole glances at each other, registering our growing discomfort and both wondering at what point we could just stand up and leave.

Then Kuntsevich began to hum, softly at first, then louder, as if he too were aware of the unbearable silence and was attempting to fill it. I didn’t recognize the tune, though the melody sounded folksy. He then snuck a peak at us, a mischievous look telling us that he was enjoying every minute of his suspenseful stunt. He pulled open a drawer and produced what looked like a vinyl record. He placed the disc on the device, wound a crank on the side, and suddenly the music Kuntsevich had been humming was replaced by the real thing, issuing from the machine. The device was a phonograph.

Later, after our translator had arrived, Kuntsevich told us that this was the music that Igor and his friends had listened to and played for one another. “They were composing poems and stories and songs, and they would perform them for one another each night.” When the song ended, Kuntsevich let the record skip and hiss for a full minute. He then replaced the record and set the needle on a new song. The wind-up nature of the player seemed to lend the mandolin, piano and folk guitar an additional layer of

sadness and longing. It was a layer that I imagined only the three of us, sitting there fifty years after the hikers had listened to similar music, could detect.

OVER THE NEXT TWO DAYS, KUNTSEVICH ARRANGED FOR

me to talk with various writers, armchair experts and other characters connected to the Dyatlov case, such as search volunteers and friends of the hikers. Though there was a translator present at each of these interviews, and I had arrived with lists of questions, I often left these meetings more confused than I’d gone in. I was learning that everyone had his or her own ideas as to what happened to the hikers, and none seemed to match the others. I was told tales of runaway murderous prison guards, top-secret military tests gone awry and a tale about mythic arctic dwarves. One man even alleged that the survivor Yuri Yudin had something to do with his friends’ deaths—after all, wasn’t it convenient that Yudin had gotten sick in the middle of the trip and had been forced to turn back? Might he have been complicit in a larger plot? Arctic dwarves aside, nearly all of these theories involved a deep distrust of the Soviet government and a belief that the euphemistic conclusion that the hikers had died of an “unknown compelling force” had been used to paper over a darker truth. Though I wasn’t yet ruling anything out, by the end of these meetings, I knew that I needed to get to people who could give me facts, not more stories out of the

Fortean Times

.

DURING OUR DOWNTIME FROM INTERVIEWS ONE DAY

, Kuntsevich, Jason and I explored the city in which the hikers had lived. I learned that Yekaterinburg—Sverdlovsk, to the Soviets—had

been founded in 1723 as part of Peter the Great’s effort to tap the riches of the Ural region. After the construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway in the late nineteenth century, the city had become a regional hub for mining, metallurgy and machine production. During the next century, the surrounding area became home to some of the largest and most brutal labor camps. Later known as

Gulags

—an acronym taken from the Russian name for the Chief Administration of Corrective Labor Camps—these camps were expanded by Stalin in the 1930s to house political prisoners, dissenters and other enemies of the State.

After making the historical rounds of the city by car, Kuntsevich pointed out the Ural State Technical University—or, as it was called until 1992, the Ural Polytechnic Institute. Westerners might know the university as the alma mater of former Russian president Boris Yeltsin; Igor Dyatlov and most of his friends would have been arriving just as Yeltsin was leaving in 1955. The proud columns and sculptured pediment of the campus’s main building were already familiar to me from pictures I’d seen, and I was keen to explore the campus beyond the quad. After some purposeful wandering, we found the hikers’ dormitory, which was closed to outsiders, but because Kuntsevich occasionally taught classes at the university, he was able to persuade a guard to let us into the building. We strolled the hallways, paying particular attention to the top-floor corridor, down which Igor and his friends had walked on the evening of their departure. I stuck my head into one of the open rooms. Quarters that might have been generously referred to as utilitarian in 1959, had slid into further neglect. I snapped a few photographs of peeling green paint and chipped stone tiles and we left.

As much as I was enjoying our city tour, by the end of the day, I was getting slightly anxious. When I asked Kuntsevich about contacting Yuri Yudin, he only shook his head or said, “I don’t know.” “You don’t know where he is?” I pressed him. “I don’t know,” he would say again, and that would be that.

But on the morning of our fourth day, our host roused us from our foldout beds with news. In his now familiar patchwork of English, Russian and hand gestures, he explained that he had scheduled a meeting with Tatiana Dyatlov Dyatlova, Igor’s little sister. I was thrilled. At last my quest was starting to seem real.

That afternoon, we took a train 30 miles west of the city to Pervouralsk, where Igor and his siblings had grown up and where Tatiana still lived. As we drew closer to her neighborhood, telephone wires multiplied over our heads, and red and white smokestacks coughed up a spectrum of grays and browns on the horizon. The sun had disappeared, but whether behind smoke or clouds, I couldn’t make out. Whereas the graffiti had only flirted with Kuntsevich’s neighborhood, it positively bloomed here, standing out as the main source of color amid cement and stone. Jason and I noted a passing rainbow of Cyrillic vandalism, speculating on what profanities it might contain.

Tatiana’s building was a midcentury relic, with an exterior coat of paint that seemed to be in the middle of a decades-long process of detaching itself from the wall. We crunched through the moat of autumn leaves surrounding the complex and past a series of mangled mailboxes in order to reach the door. We passed more graffiti on our walk to a two-toned elevator. The right elevator door appeared to have been recently replaced, leaving the left door—painted an institutional green—stranded in the Soviet era. Across both doors was a splash of vandalism in the universal language of

Fuck You

.

After an unsteady ride to the third floor, we proceeded to an apartment at the end of the hall. We knocked and, after some rustling and barks, the door opened and I found myself face to face with the features that had become branded into my memory these past few months. She must have been in her early sixties, but Tatiana’s resemblance to her brother was startling. Besides the shared eyes and sharp, Slavic cheekbones, there was the gap in her front teeth

when she smiled. She promptly ushered us through the door, as if she were worried that someone in the hallway might be transcribing our conversation.

Her dog, a Jack Russell terrier, wouldn’t stop barking, so Tatiana lifted the animal by its tail and pulled him into the next room. In contrast to what we’d seen of the building, her apartment was warm and pleasant. As we settled onto her pillowy couch, and I admired a painting above of a tranquil mountain lake, Tatiana hurried to set up tea. The table quickly disappeared under a spread of china, brass serving ware, cheese, fruit, pickles, jams, pastries and various sweets. I don’t usually notice teapots, but the one she brought out was so striking that I wondered if it was a pre-Revolution antique. Kuntsevich casually plucked four sweets off a tray while we were waiting.

Our translator arrived, a shy girl in her early twenties. Tatiana began by expressing how happy she was that we had come, and how she considered us new friends. Yet I sensed a cautious diplomacy behind her warm welcome. I didn’t want to overwhelm her, so I withheld my questions about her brother and instead made small talk about her country and our trip.

At last, between sips of heavily sugared tea, Tatiana broached the topic of her family and how their life had been before the tragedy. Besides Tatiana and Igor, there were two more siblings: their eldest brother, Slava, and, two years younger than Igor, their sister Rufina. But both had died years ago, leaving Tatiana the sole survivor.

All four Dyatlov children had been raised to be upstanding Communists, yet each had an independent spirit and inquiring mind, which they had parlayed into their respective fields of study. All four had attended UPI—Igor, Slava and Rufina for radio engineering, and Tatiana for chemical engineering. Tatiana told me that Igor had always been the most scientifically inclined of the siblings, as well as the most artistic. “He had an excellent knowledge of art,” she said. “He was a great photographer. He used to love to play the guitar, as well—he’d write songs and poems, just for himself.”

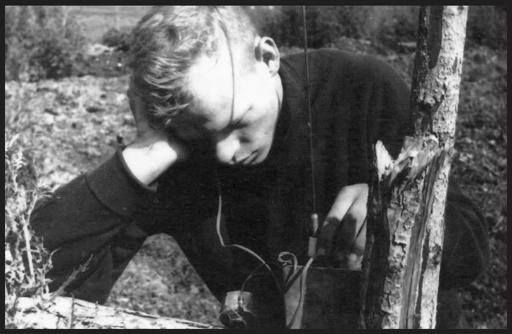

Igor Dyatlov using one of his handmade radios to communicate with another hiking group, 1957.

Through his love of photography, her brother had been able to combine his creative and technical appetites. He caught the photo bug early, and by the time he hit high school he was publishing his images in newspapers and magazines. He had also by this time turned his attention to technical invention. He built radio receivers, recording devices and even a makeshift telescope. “Igor made it possible for us to see the first Sputnik in 1957,” Tatiana remembered. “We all went to the roof to witness this historic leap of scientific wonder.”

Regarding her brother’s enthusiasm for radios, she said, “One wall of Igor’s room was completely covered with radio panels of active handmade radio receivers. He maintained shortwave communications with many radio fans, and, at the time, you couldn’t buy a shortwave radio receiver—you had to build one.”