Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident (6 page)

Read Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident Online

Authors: Donnie Eichar

The first search team boards a helicopter in Ivdel, February 20, 1959.

Chopper drop-off for search and rescue, February 1959.

Upon landing, Gordo and Blinov approach the Mansi village of Bahtiyarova, a cluster of traditional yurts insulated with reindeer hides. There, the two men learn that a group of student hikers had stopped for tea in the village several weeks before. They were the guests of tribesman Pyotr Bahtiyarov, whose family gives the village its name. The hikers’ stay was reportedly brief, and after they finished their tea, the group moved on, electing not to stay the night. After extracting what information they can from the Mansi, Blinov and Gordo take off again, flying west to the Urals. When they peer out the windows, they are able to make out the tracks of a Mansi sleigh below—evidently a native courtesy in seeing off departing guests. The tracks lead away from Bahtiyarov’s yurt and heading west toward the Urals. But the tracks stop short of the tree line, and from there, any trace of the nine hikers seems to dissolve into the wild.

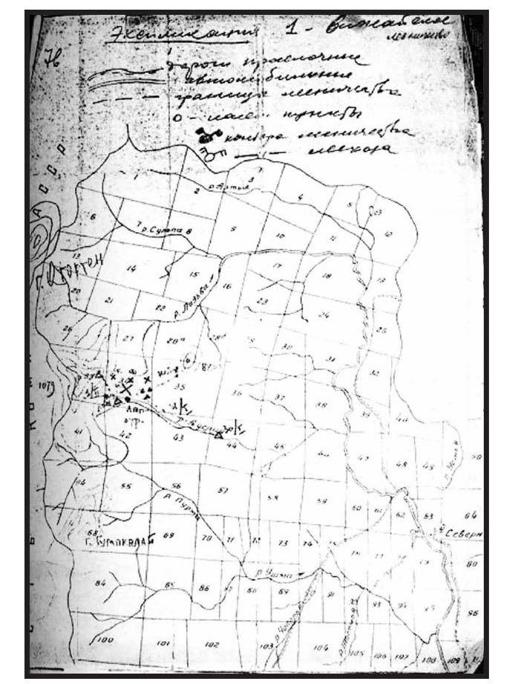

A diagram used by the rescue teams of the Vizhay forestry area indicating highways and local roads.

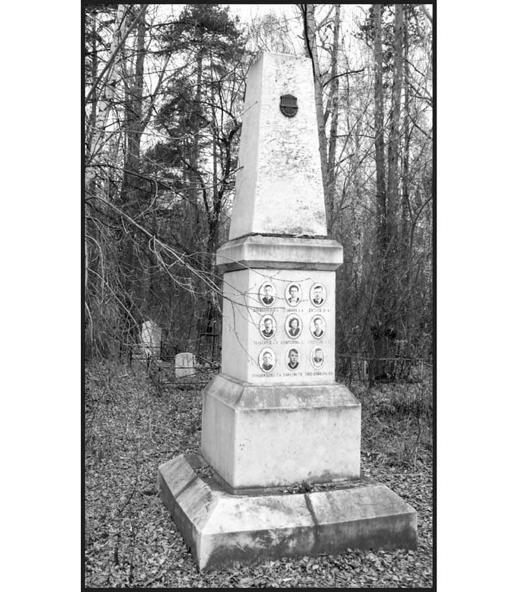

Graveyard monument to the Dyatlov group, Mikhaylovskoye Cemetery, Yekaterinburg.

4

2010

IN NOVEMBER 2010, THREE MONTHS AFTER MY INITIAL

phone call with Yuri Kuntsevich, and nine months after I’d learned of the Dyatlov tragedy, I found myself traveling to Russia for the first time. The timing wasn’t ideal. My girlfriend, Julia, was seven months pregnant and we were going through all the related joys and upheaval of becoming parents. But we also knew that once the baby arrived, there would be little time for me to spend on the case—so to Russia I went. My close friend of twelve years and film-producing partner, Jason Thompson, graciously agreed to drop everything in order to join me on the trip. Jason shared my enthusiasm for the Dyatlov case and my need to know what happened to the hikers. We flew into Moscow and caught a connecting plane east to Yekaterinburg by way of Aeroflot. Founded by the Soviet government in 1923, Aeroflot is one of the oldest airlines in the world and is the same state-owned airline whose planes were employed in the search for the Dyatlov hikers. In fact, the company’s original insignia, a winged hammer-and-sickle that was emblazoned on the sides of the rescue planes, is still used by the company today.

I was unsure what would happen once we touched down in Yekaterinburg, but I had decided to tamp down the neurotic producer side of my personality and just let the trip wash over me. At this point, my dedication to the project was still in the exploratory stage. I had been initially obsessed with the case, sure, but I wasn’t

certain how much of my life I could realistically afford to devote to it. Even so, I kept turning over the same questions: What led the hikers to leave their only shelter? Could the explanation be as simple as an avalanche? Were there really still classified case files hidden away in the Russian archives, as Kuntsevich had told me on the phone? And where was Yuri Yudin?

Over my final weeks of trip preparation, I had also become eager to make contact with Igor Dyatlov’s younger sisters, Tatiana and Rufina, who were rumored to still be living near Yekaterinburg. But like Yudin, after half a century of invasive questions from writers and journalists—many concerning unsubstantiated and salacious claims about the hikers’ personal lives (a lover’s quarrel, jealousy, group in-fighting)—they weren’t exactly handing out interviews.

It was early morning when we landed just southeast of Yekaterinburg at the Koltsovo International Airport. Built under Stalin in the 1920s as a military air base, the airport was now an international hub, the fifth largest in the country. At that point, I was grateful to have Jason by my side to share my total disorientation and lack of anything resembling a plan. All I knew was that we were meeting my one contact, Yuri Kuntsevich, somewhere near the airport exit. I’m not proud to admit that my image of the Dyatlov Foundation president up to this point had been fairly cartoonish. I half expected to meet a bearded, unsmiling tank of a man who smelled faintly of vodka and cruciferous soup.

We exited the international terminal and were funneled into a crush of anxious drivers bearing signs of identification. I began to look for my own name, hunting for Roman lettering amid the Cyrillic, when two words in wobbly black marker caught our attention. The sign was unmistakable and, despite its dark meaning, I smiled when I read it: “Dyatlov Incident.” On seeing Kuntsevich in the flesh, my image of the Russian hulk vaporized and was replaced by that of a kindly father figure. Kuntsevich was far into middle age—mid-sixties—but his remarkably square, doll-like face still

clung to youth. On our approach, he smiled broadly and let the sign drop to his side. The three of us exchanged handshakes and brief hugs, but aside from some broken English on his part and a few shards of phrase-book Russian on ours, we said little.

Having been shunted from plane to plane for the previous twenty-six hours, I was desperate to step outside. It was still fall, and there was no snow on the ground yet, but the second we stepped into the early morning air, I craved heat. We followed our host to a Renault. But either the heater wasn’t working in the car or the driver preferred not to use it. From the backseat, Jason and I listened to Kuntsevich speak insistent Russian into a cell phone that hung about his neck.

We traveled north to the city. Aside from the faint outline of smokestacks against the sky and the lights of the metropolis flickering in the distance, I could make out little else. For me, the city’s significance revolved entirely around the Dyatlov hikers and the university, but for most first-time visitors, the place held the psychic residue of a very different tragedy. In 1918, after the three-centuries-old Romanov dynasty had fallen to control of the Bolsheviks the previous year, Czar Nicholas and his family were imprisoned in Yekaterinburg’s Ipatiev House at the center of the city. In mid-July, as the country’s civil war continued to roil and the anti-Communist White Army threatened to take back the city, the order was given to execute the entire royal family. In the early morning hours of July 17, the czar and czarina, along with their five children and various attendants, were brought to the building’s basement where they were lined up—ostensibly for a family photograph—and executed at point-blank range. The scene was a protracted bloodbath. Those who did not die immediately by bullet were stabbed with bayonets. It would take yet another revolution, some seven decades later, before the Romanovs’ remains would be recovered from a swamp outside the city. As I looked out at the lights of Yekaterinburg and to the imagined swampland beyond, I thought of how the family’s

bones had lain somewhere out there for decades, forgotten under a blanket of peat. Yet even after their bodies had been given a proper burial, the myths surrounding their deaths persisted—the most famous of which was that young Anastasia had escaped assassination to assume a new identity overseas. Russian conspiracy fabulists, it seems, never let facts get in the way of a good story.

When the buildings began to shift from grand neoclassical to boxy and austere, we were nearing Kuntsevich’s working-class neighborhood. Everything was orderly, though there were hints of neglect and flourishes of graffiti. Once we entered Kuntsevich’s complex, the smell of natural gas hit us like a wave. Intermittent fluorescents offered the only light, leaving slices of the hallway in shadow.

The two-bedroom apartment Kuntsevich shared with his wife was cozy—the modest space of a couple making do—and they were generous to accommodate us during our stay. We put on rubber slippers at the door and, as the sun rose, Kuntsevich’s petite wife, Olga, set to work fixing an early breakfast. I watched her with an immediate fondness. Beneath her halo of dark hair, she had kind brown eyes and a sweet smile that reminded me of my late grandmother. The likeness made me feel close to this woman with whom I could barely communicate.

Olga led us to the kitchen where, on a table the size of a car tire, she served us piles of dark meat and root vegetables. Afterward, our host walked us down the street to the Military History Museum, where we took a brief tour of emasculated tanks, cannons and other artillery. We then got in the car and drove to the Mikhaylovskoye Cemetery at the center of town, where all but one of the hikers were buried. Kuntsevich, Jason and I crunched through dead leaves and undergrowth to the edge of the yard where eight marble headstones sat in a row along the border fence. Artificial lilies had been placed at each grave some time ago, and were now half-buried in leaves or weeds. Except for the names and years of birth, the stones were identical, and they all bore the same end: 1959. The

Krivonishchenko family had chosen to bury Georgy in a separate cemetery a few miles to the west, but Georgy was represented on a commemorative column nearby, on which nine black-and-white portraits had been preserved in marble. After a shared moment of silence, I took a few pictures and we made our way back over the neglected grounds to the car.

By midmorning, we were back in the car driving hours outside of town to the dense forest abutting the Ural Mountains. At this point, Jason and I had been awake for more than thirty hours and we couldn’t figure out why, having just arrived in this country for the first time, Kuntsevich was taking us on what appeared to be an impromptu camping trip. Though we were on the verge of sleep-deprived delirium, Jason and I went along with the rest of the day’s activities. We cut wood with a crosscut saw I thought only lumberjacks used. Over a campfire, we cooked a small bony fish that Kuntsevich had brought, and drank a batch of spiked fruit juice. I wondered if we would be pitching a tent next, but as night fell, Kuntsevich drove us back to the city. Perhaps this spontaneous excursion had been a kind of Russian endurance test, and our host had been assessing our stamina as outdoorsmen, and possibly as friends.