Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident (17 page)

Read Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident Online

Authors: Donnie Eichar

At some point, Borzenkov and I became engaged in a side-by-side comparison of our respective gear, a contest that seemed to carry with it a certain Cold War one-upmanship. If I had been harboring any lingering feelings of superiority about my fancy outerwear or highfalutin boots, Borzenkov quickly shot me down with a display of his impressive Russian headlamp—which, he pointed out, was of a more solid construction than my made-in-the-USA equivalent. More embarrassing were the shell pants I had thought such a wise purchase several months ago, which ended up not fitting around my fancy Arctic-model “elephant boots,” as Kuntsevich dubbed them. The miscalculation would have me running around last-minute to find Russian-made snow pants fit for the journey.

As we counted down the days to our departure, Kuntsevich, Borzenkov and I were already kidding around with friendly ease—through Taranenko’s translations. Our banter held the familiar lightness of tone that tends to happen in the face of a serious task. It reminded me of the gaiety of dorm room 531 on January 23, 1959,

as Igor and the others packed for their last adventure together. As I glanced at Yudin, I wondered if he was thinking of that night as he observed our preparations.

Yudin hovered around us, stopping every once in a while to make private notes on scraps of paper. Whether these notes were vital, or Yudin simply wished to look busy, I wasn’t sure. Occasionally, he’d chime in to the conversation, but most of the time he was a silent presence in the room, content to observe the activity around him. Tragedy couldn’t have been far from his mind, as his constant refrain in the days leading up to our expedition was, “I am praying for your safety.”

ON THE AFTERNOON OF THE DAY BEFORE OUR DEPARTURE

, Kuntsevich’s wife pulled me and the translator into the kitchen. What I assumed was another of Olga’s afternoon tea breaks or a surprise serving of

salo

—a delicacy made from cured pig fat—turned out to be a private talk out of earshot of the others. She told me in a near whisper that her husband was very worried for my safety, so much so that he was considering canceling the trip entirely. Her concern touched me, but I assured her—while ignoring my own doubts—that everything would be fine, I was certain of it.

When I rejoined the others, Kuntsevich was soberly discussing the weather forecast, which he pointed out was particularly difficult to predict in the region from Ivdel to the mountains. He explained that we would have to bypass the village of Vizhay, where the hikers had stayed for one night. A wildfire had struck the village in the summer of 2010, consuming thirty-four buildings and resulting in the entire community’s evacuation to Ivdel. Similarly, Sector 41 no longer existed, as such woodcutting settlements had typically been razed after five years of use. We would, however, be

staying in Ushma, a Mansi village located along the Lozva River, five miles downstream from where the hikers had spent the night in Sector 41. Lacking the modern conveniences of running water and electricity, Ushma was the closest we could come to spending the night as the hikers had done.

Kuntsevich’s worry was that in the 45 miles between Ushma and Dyatlov Pass, a region known for its hurricane-force winds, weather prediction was utterly useless. The temperate forecasts were saying minus twenty-five degrees Fahrenheit, the same estimated temperature the hikers had experienced on their last night together. But even that prediction could change for the worse.

Having never experienced these kinds of brutal temperatures firsthand, I started to get a little nervous and, amid all the talk of worst-case scenarios, I had to suppress my own feelings of escalating dread. My talk in the kitchen with Olga had only made me more aware of the concern I saw on Kuntsevich’s face whenever he looked in my direction. If the stoic Russians were this nervous about our journey into the northern Ural Mountains, how was I supposed to feel?

Our morning call time was seven o’clock, and as I prepared for bed, I gave myself a mental pep talk. This hike was exactly what I was supposed to be doing, I told myself. It was what I had been wanting for several years. Before I could disappear into my room for the night, Borzenkov pulled me aside with one last bit of mountaineering wisdom, delivered in halting English. I was expecting another warning—a

remember to

, or

never

, or

always

—but instead he told me not to bother packing a toothbrush. He didn’t tell me why, but he said it with such gravity, that for a second I believed it to be sage advice. In the end, I made sure that my toothbrush was easily accessible in the side pocket of my pack. My new friend, after all, was missing a significant number of his teeth.

The last bit of business before bed was to call my family. First, I called my girlfriend on Skype, in what turned into a teary half-hour

exchange, at the end of which I promised her that I’d return home safely. Even more poignant was my son’s puzzled look as he stared at the computer screen at a face he was having trouble placing, but one that his mother kept referring to as “Papa.” His lack of recognition cut my heart in half. I had only been gone a couple of weeks, but to a one-year-old, that was an eternity.

The last call was to my mother, whose refrain throughout this quest of mine had been: “Why are you doing this?” When my mother asked me again, “Why are you doing this?” I didn’t have a satisfying answer for her. I told her not to worry and that I’d be home soon.

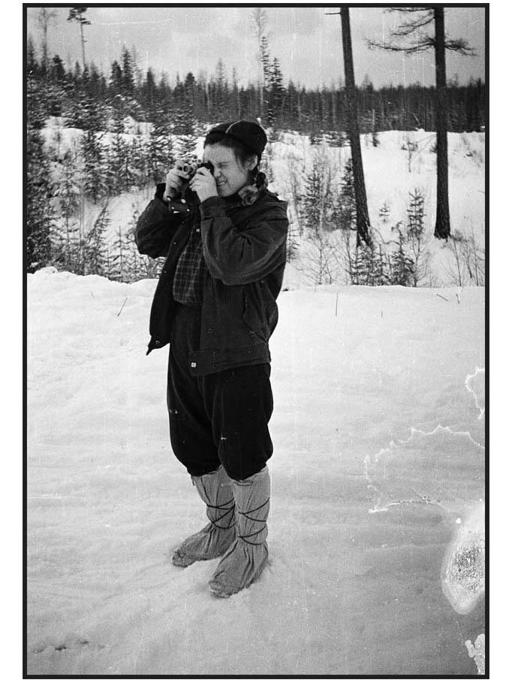

Zinaida “Zina” Kolmogorova in Sector 41 wearing the boot covers she made in Vizhay, January 27, 1959.

15

JANUARY 26–28, 1959

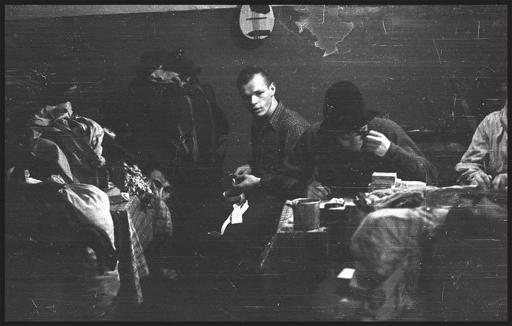

THE WOODCUTTERS LIVING IN SECTOR 41 HAD LIKELY NOT

seen a woman in months, and when the truck bearing the ten hikers came into view, the two women aboard must have sent a collective tremor through the laborers’ hearts. It was about an hour before sunset, and, as the hikers climbed out of the truck to greet their hosts, there was still enough light for the strangers to see each other clearly. The woodcutters were bundled in the standard outerwear of the region: trapper’s cap and

telogreika

—a quilted cotton jacket originally designed for the Red Army. The men had young, unlined faces, and the hikers recognized that they were not much older than themselves. Among those who greeted them, there was one proud man who stood out from the rest. He had dark, disheveled hair and a full red beard. He introduced himself as Yevgeny Venediktov, though Georgy noted he had a fitting nickname.

We were talking to local workers about all kinds of things for a rather long time, and one red-bearded worker stayed in memory, his fellows called him “Boroda.”

Boroda (the Russian word for “beard”) considered himself the spokesman of the group, and he took immediate charge in finding rooms for their guests. Aside from a series of pine log cabins that

served as dorms for the workers, there was little to see at Sector 41. The settlement was like many of its kind in the region—a collection of roughly fifty men sent out on long-term contracts to harvest, chop and haul wood from the surrounding forests. The life of a woodcutter was an isolated one, and it took men away from their families for extended portions of the year. But then, for Soviets who lacked a formal education, manual labor was often their best option. Perhaps it was at moments such as these that the ten hikers felt lucky to have been awarded a place at the university; even under Khrushchev, there were many young people whose opportunities were startlingly limited.

While the woodcutters were enlivened by the appearance of unexpected guests, the hikers were simply relieved their windblown ride was at an end. There was dinner and sleep to look forward to, and, for Yuri Yudin, there was the temporary reprieve from the painful jostle of travel. The ten friends unloaded their packs from the truck. After displacing some of his fellow workers, Boroda managed to free up a separate room for their female guests. Lyuda and Zina appreciated the gesture, but as it happened, there would be little time for sleep that night.

The woodcutters made bread for their visitors, and after dinner, everyone gathered around the wood-burning stove for warmth. The cabin offered none of the comforts of the Vizhay guesthouse. The furniture was Spartan, and patches of swamp moss wedged between the logs were the only thing keeping out the bitter draft. But the cabin was luxurious compared with the accommodations that lay ahead for the hikers, and they were surely grateful for the warm reception and company. In fact, the students from the city found that they had more in common with these rural laborers than they might have guessed. It was true that the woodcutters had the wiry bodies of men who made their living from the land, but they also had the minds of self-taught intellectuals and the hearts of poets. Of all the men, the hikers found Boroda to be the most like-minded. Not only could he recite poetry as if he were reading it from the pages of a book, but he also held an easy sway over the entire group. “He was clearly the smartest,” Yudin recalls, “and he had immense authority among the guys.” Boroda also had a striking personal style for a man who spent most of his life in the woods. His reluctance to shave may well have arisen from convenience, but when paired with his smart blazer and Cossack-style breeches, Boroda’s generous facial hair lent him a surprising air of sophistication. It was as if he were making a conscious fashion statement, even if out here in the Russian wood there were few to admire it.

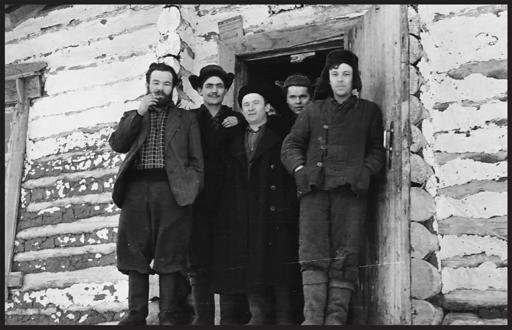

Sector 41 woodcutters. Far left, Yevgeny “Boroda” Venediktov, January 27, 1959.