Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident (14 page)

Read Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident Online

Authors: Donnie Eichar

Odder still had been Yudin’s expression of his devotion not just to Stalin, but to Communist rule in general. How was Yudin able to reconcile a deep affection for the Soviet era, while carrying around an intense suspicion of its government? How could the same government that had provided for him and his family so well, who had given him a free education, be the same government responsible for, at best, whitewashing what happened the night of February 1—or, at worst, killing and torturing his closest friends? But Yudin’s apparent love-hate relationship with strong rule was certainly not unique to him; one had only to look at his country’s volatile history to see that this kind of ambivalence appeared to be stamped into the Russian genetic code.

Still, I was enjoying my days with Yudin and looking forward to having him beside me to provide commentary during our upcoming trip. But, as I would soon find out, my face time with the Dyatlov group’s survivor would be limited. The next few days would bring discouraging news to the Kuntsevich house, as well as a surprise visitor from Moscow.

The Dyatlov hikers depart Vizhay for Sector 41, January 26, 1959.

12

JANUARY 25–26, 1959

THEY HAD BEEN EXPECTING NOTHING MORE THAN HUMBLE

accommodations in Vizhay: just a roof over their heads and a floor on which to stretch out. But when Igor introduced himself and his companions to the director of the free workers’ camp, the man took an instant liking to the young adventurers and insisted they spend the night at the camp’s guesthouse. There they would be well taken care of and each provided with his or her own room. Yudin describes it as the most “posh” house in the settlement, a mansion in comparison with what they were used to. “It was very chic for those times,” he says.

The instant they stepped over the threshold into their well-appointed lodgings, they were conscious of their grimy state. “The linens were spotless,” Yudin remembers. “I was missing a pillowcase and a woman promptly found me a replacement.” He adds, “The cleaning ladies, they were furious because they had to clean the whole place after we left.”

After unloading their packs and spreading out in their luxurious digs, the hikers lit the wood-burning stove and started dinner. There were other tasks. Zina finished assembling her tarpaulin boot covers and Rustik wrote a postcard to his family. After dinner, there was talk of going into town. As chance would have it, the group’s favorite movie,

Symphony in Gold

, was playing at the local cinema. The 1956 Austrian musical, which features an attractive cast ice skating its way

through a snowy wonderland and effervescent musical numbers, was just then making its rounds in Soviet theaters. The hikers had seen

Symphony in Gold

multiple times and knew many of the songs by heart, even though the lyrics were in German. One particular number, “Dong Dingeldang,” features an idyllic mountain landscape populated by a troop of young skiers buoyantly advancing through the snow. Apart from all the yodeling, and the comic arrival of an ice-skating bull, it’s hard to imagine Igor and his friends not having seen themselves reflected in this scene of winter adventure and joyful song.

While the others were at the “cinema”—which was likely little more than a community projection room with folding chairs—the ever-sensible Kolevatov, with the help of Doroshenko, stayed behind to clear away the clutter from dinner. Referring to himself in the third person, Kolevatov noted somewhat bitterly in the group’s diary:

Doroshenko and Kolevatov are left to do housework, while the others go to the cinema and return in “musical mood” after seeing Symphony in Gold

.

THE NEXT MORNING, THE TRAVELERS LEARNED THAT THE

truck headed to Sector 41 wouldn’t be leaving until that afternoon. This gave them ample time to pack and secure some breakfast. Georgy’s diary notes:

We didn’t cook in the morning, firewood is damp, and cooking took 6 hours in the evening. We went to the cafeteria for breakfast and had goulash a-la-cafeteria and tea

.

The goulash didn’t present any particular reason for complaint, but the hikers were disappointed when their tea arrived unheated.

Igor, however, took the nuisance in stride. According to Georgy’s diary, he quipped, “If the tea is cold, drink it outside and it will seem warmer.”

After breakfast and packing, the morning’s main task was to gather some final supplies in town and to get advice from the local forester. “In any settlement, the first visit was paid to foresters,” Yudin explains, “because they knew the roads and could advise visitors on their route.” Vizhay’s resident forester was a man named Ivan Rempel. He was unusual among those in his profession in that he was part of a population known as Russified Germans, transplants from Germany who had embraced Russian culture and were fluent in the language.

Despite the forester’s convincing assimilation, there was an aspect of his house that had retained the flavor of his home country, something Yudin noticed immediately upon entering. First, the house was exceedingly well kept. But most notably, Rempel had fashioned a section of his house in the likeness of a

Wunderkammer

or “wonder room”—what the English would call a cabinet of curiosities. The walls were covered in paintings, many of them done by Rempel himself. But most captivating to his visitors were shelves upon shelves of glass jars filled with miniature tableaux. Each jar featured a different shrunken landscape, and many were religious or seasonal in theme—motionless versions of the scenes Yudin and his friends had enjoyed at the cinema the night before. There were depictions of the Nativity, Christmas trees, winter vistas featuring children and sleighs and—the Slavic version of Santa Claus—Father Frost. While Igor and his friends were consulting with Rempel, Yudin couldn’t keep his eyes from the diminutive figures suspended behind glass, and from the tiny Christ child lying in an equally tiny manger. To this day, Yudin can’t understand how the forester managed to construct such tiny wonders. “How he got them in there, nobody could figure out.”

While Yudin was enraptured by these fantasy snowscapes, the forester warned the rest of the hikers of the real winter conditions outside. After Igor expressed the group’s intention to reach Otorten Mountain, the forester strongly advised against such a trip. “I expressed my opinion that it is dangerous to go over the Ural ridge in winter,” Rempel later said, “as there are large ravines and pits where one can sink, and winds are so strong that people can be blown away.” Rempel told the hikers that although he hadn’t experienced these dangers firsthand, he had heard stories of locals making the mistake of similar trips.

But whatever argument the forester made, Igor insisted that they were looking for a challenge. “We are prepared, we’re ready, we’re not afraid,” Yudin remembers Igor saying. “The level of preparation for the campaign of the Dyatlov group was much better than that assumed by local residents.”

Even if Igor had believed that significant danger lay ahead, as the forester was insisting, he wouldn’t have let that discourage his group. Igor was “a fan of extremely dangerous situations—an addict,” Yudin says. “He was deliberately finding and choosing the most dangerous situations and overcoming them.” Perhaps, then, the forester’s warning had the opposite effect to the one intended: It only convinced Igor that he and his friends were on the right path. After Igor copied down one of Rempel’s maps, which was more detailed than the one they were carrying, the friends thanked the forester, cast a last glance at the miniature curios and went on their way.

It was around this time that Yudin began to have serious doubts about continuing into the mountains. It had nothing to do with the forester’s warnings and everything to do with the increasing pain shooting through his back and legs. Yudin informed the group of his discomfort—stated merely as fact, not as a complaint—but also said he fully intended to push ahead to Sector 41.

That afternoon, the ten bundled friends piled into the bed of a woodcutters’ truck, one primarily used for shuttling workers to and from the camps. As Yudin would discover during the three-hour truck ride, this form of transportation was not designed for someone combating rheumatism. Aside from the extreme cold, every bump and irregularity in the road seemed to magnify his pain. He could do little about the roughness, but he resorted to unfurling the group’s tent and pulling it over himself like a blanket to keep warm. Georgy noted how the friends tried to make the best of an uncomfortable journey:

Got pretty cold, as we were riding in the back of a GAZ-63. We were singing all the way, discussing various issues, from love and friendship to cancer diseases and treatment

.

“The wind was blowing in our faces,” Yudin remembers. “The temperature was very low and my clothes were very thin.” Yudin would later catch cold because of this ride, but then a cold was trivial as compared with his lifelong struggles with illness. “It’s a Russian way of thinking. When we are ill, we think, OK, I’m not going to the doctor. I’m not going to lie about it either, but maybe it’ll go away.”

Though he had told his friends that he intended to push onward, Yudin knew he wouldn’t be able to bear such pain once they were deep in the Urals. There was only so much relief the medicine in his pack could provide. As the truck rattled its way to Sector 41, and Yudin’s bones rattled along with it, he was keenly aware that at some point there would be no turning back. He would have to make a decision soon.

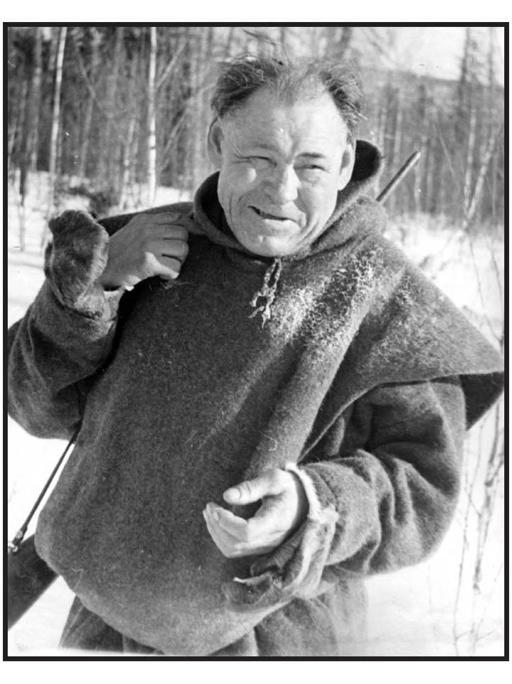

Stepan Kurikov, head of the Mansi search team, February 1959.