Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident (18 page)

Read Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident Online

Authors: Donnie Eichar

The Dyatlov hikers in their Sector 41 quarters. Igor Dyatlov (middle) and Nikolay “Kolya” Thibault-Brignoles (right, wearing hat). Yuri “Georgy” Krivonishchenko’s mandolin hangs on the wall behind them, January 27, 1959.

Over multiple cups of black tea, which was in plentiful supply from China during that time, Boroda and his crew recited their favorite poems for their guests. “Even though they worked as forest cutters, they knew Yesenin and his poems,” Yudin remembers. “So that shows that they were smart, not just working class.” Sergei Yesenin was a lyrical poet of the early twentieth century, one of the most celebrated in Russia. He had been an early supporter of the Bolshevik Revolution, but his later criticism of the government compelled Stalin to ban his work—a ban that had remained in place through Khrushchev’s regime. Yesenin had also been plagued by mental illness, and at the age of thirty hanged himself. But just before ending his life, he wrote what would become one of his most famous poems:

Good-bye, my friend, good-bye

My love, you are in my heart.

It was preordained we should part

And be reunited by and by.

Good-bye: no handshake to endure.

Let’s have no sadness—furrowed brow.

There’s nothing new in dying now

Though living is no newer

.

Poetry lovers living in the Soviet Union would have had to memorize poems such as this one, as it was difficult to find Yesenin’s work in print. “You couldn’t read his books,” Yudin explains. “They were forbidden. You couldn’t buy them anywhere. . . . But even though he was forbidden—as were many other poets and writers—somehow we managed to have conversations about him.”

As often happens, talk of poetry among young people turns to talk of love and relationships. And that night the two women steered the conversation toward romance. Yudin remembers that the two women were fond of this type of talk, and they had often brought up the subject back at the UPI dorms. “So every day since we left Yekaterinburg they were talking about love. They were trying to express something and to get to know something from the guys.”

Only a couple of days earlier, Yudin had noted as much in the group diary: “Dispute about love provoked by Z. Kolmogorova.” Zina evidently wasn’t finished with the dispute, and her male hosts provided a fresh perspective on the subject. But Zina’s motives, as well as Lyuda’s, were entirely innocent, Yudin says. Most members of the group, including both women, were virgins. “Life was different in those times, and the atmosphere was different. Nobody would understand that now. Everything was romantic, but the romance meant something different.”

Yudin admits that the male members of the hiking group—Igor, Georgy and Doroshenko, in particular—had crushes on Zina, but he says there was shame attached to expressing interest in one person. “Of course, we had some romantic feelings toward each other, but nobody said anything because you couldn’t pay attention to one girl. It wouldn’t be the Soviet style of doing things.” Of the talk that night at Sector 41, Yudin says, “Of course we had affections toward each other, but the talks were about love in general, not in particular. . . . What is love? What is romance? Who’s the perfect girl, the perfect type of girl?”

The friends may have preferred to speak of their feelings in universal terms, but they didn’t hesitate to sing and dance with each other, celebrating the romance of being young, together and, perhaps, secretly in love. The musical Rustik took a turn on Georgy’s mandolin, while one of the woodcutters produced a guitar. Among the many songs of the evening was “Snow” by the Russian poet and adventurer Alexander Gorodnitsky, whose songs were popular among young travelers.

Silently slowly sliding snow,

Crackling twigs in the sputtering fire,

Everyone’s still asleep but I

—

What’s on my mind?

It’s snowing snow, snowing snow,

Priming the tent’s canvas in white

Our short stay overnight

Is almost over

.

It’s snowing snow, snowing snow,

Painting the tundra around us white;

Making the frozen rivers alight,

Snowing snow

.

All this celebrating was, of course, conducted without consuming alcohol—at least for the hikers. “Nobody drank, among the tourists, nobody,” Yudin insists, though he admits that he and his friends made exceptions on special occasions. On one particular New Year’s Eve, a group of roughly one hundred students went camping, bringing two bottles of champagne to go around. “Everybody had a spoonful of champagne and that’s it. But we were dancing and singing all night, because we didn’t need alcohol to have fun.”

And so, without the aid of beer, wine, or moonshine, the students laughed with their hosts, stomped on the wooden floorboards and generally amused themselves until there were only a few hours of remaining darkness. Only then did they retire to their rooms and fall into a much-needed sleep. The group had a difficult day of travel ahead of them. They were now finished with motorized transportation; it was time to ready their skis and test their physical abilities in the wild.

Yuri Yudin did not sleep soundly that night. He awoke from his bed on the floor to an even worse pain than he had experienced the day before. Yet he was determined to push ahead. His stubbornness, he says, was partly due to his wish to continue the trip with his friends, but he had his own private reasons for not turning back. The next stop was an abandoned geologic settlement—and because Yudin was studying geology at school, he was curious to see what minerals and gemstones he might find amid the deserted buildings.

After a late breakfast, the woodcutters filed out of the cabins to see their new friends off. Boroda emerged with an unruly mane and a cigarette between his fingers. When he realized proper group photographs were being taken, he smoothed back his hair and assumed a pose with his Comrades. As a parting gesture, the hikers presented their hosts with gifts, whatever possessions they thought they could spare. One of the Sector 41 workers, Georgy Ryazhnev, later revealed to investigators, “They presented master Yevgeny Venediktov with a fiction book and gave a present to Anatoly Tutinkov as well.”

That afternoon, a Lithuanian named Stanislav Velikyavichus arrived with a horse-drawn sleigh to escort the hikers to the geologic settlement. Velikyavichus was on an errand that day to pick up iron pipes from the abandoned site, and, as luck had it, his sleigh had room enough to hold the hikers’ packs. He was a freelance worker at the settlement, and having been imprisoned

for six years at Sector 2 of the eighth department of penitentiary camps, he was the travelers’ first encounter with a former convict of the region. What Velikyavichus did to earn his imprisonment isn’t clear, but, whatever his crime, Sector 41’s director didn’t see any reason not to put the hikers in his trust. Neither did the hikers, who would affectionately dub him “Grandpa Slava.”

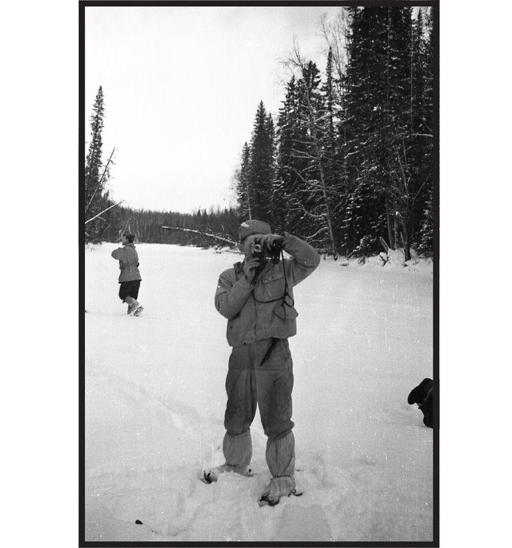

Because Velikyavichus arrived so late in the day, the trade-off for a lightened load was that they would be making much of their 15-mile trek by moonlight. The ten skiers said farewell to their woodcutter friends and proceeded north from Sector 41 deeper into the forest. Though they were temporarily relieved of their packs, the skiers had 15 miles of difficult country to cross before reaching the next settlement. To break up the monotony of travel, the friends would stop periodically, and cameras would appear from beneath their coats. A visual record of their progress was crucial in earning their next hiking grade of III. By capturing their journey on film, they could prove to the university that they were complying with the various hiking codes: regulation clothing, proper gear and skiing in proper formation. This didn’t stop them from mugging for the camera occasionally, and a fair portion of film was devoted to less serious documentation, including swapping hats and adopting exaggerated poses. A look at their album reveals typical college students clearly enjoying each other’s company.

There was thick forest all around them, and the easiest path through the snow was up the frozen Lozva River. Yudin says the ice wasn’t very thick, and it wasn’t cold enough to completely ensure against their skis penetrating through to the water. What’s more, the sticky snow would turn to ice on their skis, compelling them to stop periodically and slice away the ice with a knife. But, in doing so, they had to be careful not to put too much weight on the river. “It was very difficult and dangerous,” Yudin remembers. “The river was covered in snow and you couldn’t see the ice you were standing on.”

Group photo at Sector 41, January 27, 1959.

The Dyatlov hikers en route from Sector 41 to the abandoned geological site. From front to back: Yuri Doroshenko, Zinaida “Zina” Kolmogorova, Lyudmila “Lyuda” Dubinina, Stanislav “Grandpa Slava” Velikyavichus. Yuri Yudin can be seen in the far background, January 27, 1959.

Nikolay “Kolya” Thibault-Brignoles plays in the snow assuming positions of faux distress, January 27, 1959.

From left to right: Lyudmila “Lyuda” Dubinina, Yuri “Georgy” Krivonishchenko, Nikolay “Kolya” Thibault-Brignoles, and Rustem “Rustik” Slobodin, January 27, 1959.