Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident (33 page)

Read Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident Online

Authors: Donnie Eichar

“Wait,” I asked him, “so was it Kármán vortex or infrasound?”

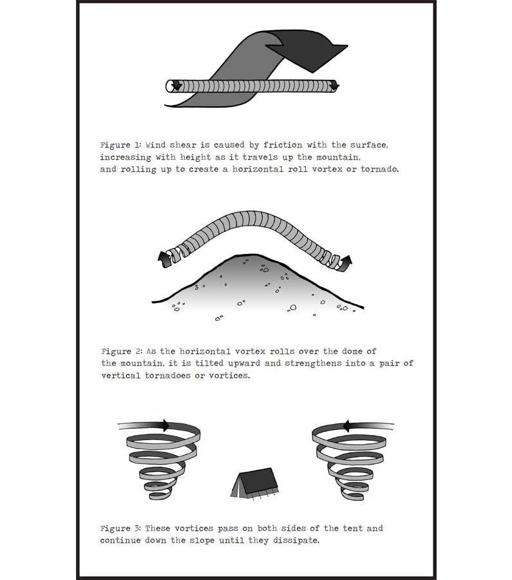

Both, he said. It would be difficult to come up with a more ideal confluence of weather and landscape to create Kármán vortex street—with vortices that would produce infrasound. These vortices would have been screaming right outside the hikers’ tent that night, creating an intense discomfort and fear that they couldn’t begin to understand. “I can imagine they’re all in the tent,” Bedard said. “They start to hear the winds pick up. . . . Then to the south they start to feel a vibration in the ground. They hear a roar that seems to pass them from west to east. They start to feel more vibration in the floor, the fabric of the tent vibrates. Another roar of a freight train passes by, this time from the north. . . . The roaring sounds turn horrifying, their chest cavities begin to vibrate from the infrasound created by the stronger vortex now passing. Effects of infrasound are beginning to be felt by the hikers—panic, fear, trouble breathing—as physiological frequencies are generated.”

From what Bedard was telling me, it sounded as if the nine hikers, on the night of February 1, 1959, had likely picked the worst spot in that entire area of the northern Ural Mountains to pitch their tent. “I can envision in my mind,” he said, “that this would have been a truly frightening scenario . . . for anyone.”

Dr. Bedard then summed up my entire three-year quest in a beautifully concise way: “What you’re really trying to do is reverse-engineer a tragic event without any witnesses.” But without any witnesses, without my having been there on Holatchahl mountain on that night in February, there was no way for me—or anyone—to know with absolute certainty what sent the hikers fleeing from their tent. Yet at that moment, listening to Dr. Bedard describe how the mountain and the wind could generate this elegant pattern of swirling air—and therefore the panic-inducing infrasound— I found it the most convincing theory I had yet heard.

Besides experiencing an immediate and intense sense of relief, I marveled at the simplicity of it: All along, the culprit had been the mountain that the native people had so ominously named. Had you told me three years ago that the elevation at 1,079 meters, what the Mansi called “Dead Mountain,” could have been so directly responsible for the hikers’ tragic end, I would never have believed it.

ON FEBRUARY

15, 2013,

THE DAY AFTER I RETURNED HOME

from Boulder, an infrasound event hit western Siberia. I didn’t initially connect the event to infrasound. Like most people who read the news that morning, I registered the occurrence as a gee-whiz oddity—if an alarming one. Just after dawn, at 9:20 local time, a twelve-thousand-ton meteor exploded in the sky over the Ural Mountains, 120 miles south of Yekaterinburg. NASA scientists estimated its diameter to have been 55 feet, making it the largest meteor to hit Earth’s atmosphere in over a century since the Tunguska meteor event of 1908. That meteor—thought to have been approximately 130 feet across—had resulted in an explosion that flattened 800 square miles of forest in central Siberia, with a blast several hundred times more powerful than the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

Unlike the remote Tunguska event, the meteor on February 15 struck the atmosphere above Chelyabinsk, a city of more than one million people. The meteor broke apart between 12 and 15 miles above Earth, in a bright white explosion accompanied by an intense

aftershock. The pressure of the explosion blew out windows across Chelyabinsk—a million square feet of glass by one estimate—and injured more than 1,200 people.

Not only one of the largest meteor events in recorded history, the Chelyabinsk meteor was also one of the most documented. Motorists all over the region had recorded the event on their “dash cams”—a popular added feature on Russian cars—with many of those drivers able to view the event from the safe distance of Yekaterinburg, where citizens could see a flaming fireball streaking across the southern sky.

Having been at NOAA just the day before, I shouldn’t have been surprised to learn that a by-product of the meteor blast had been infrasound waves, generated when fragments of the rock decelerated in the atmosphere. These subsonic waves had been picked up by a global network of infrasound sensors, operated by the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO), an international body established for the purposes of monitoring nuclear detonations. On February 15, the CTBTO network measured infrasonic waves as far as Antarctica, more than 9,000 miles from Chelyabinsk. Though the waves were capable of traveling thousands of miles, the effects of the infrasound in Chelyabinsk itself were relatively short-lived. This was not the sustained infrasound as would be generated by a Kármán-vortex-street wind event, but a swift and violent burst of infrasonic waves. According to scientists, the infrasound resulting from the meteor’s deceleration had, in part, been responsible for the shattering of windows in Chelyabinsk.

Over the next few days, news of the event included reportage of the infrasound sensor network and numerous mentions of the subsonic waves and their effects—bearing out Dr. Bedard’s affirmation that the science of infrasound had been enjoying increased recognition over the past decade. Though monitoring of infrasound had begun years earlier, during the Cold War, the understanding

and detection of the phenomenon is not close to what it is today. The first CTBTO global infrasound detector went online in April 2001, followed by more than forty sensors over the next decade. Currently, 45 of the 60 planned sensors of the CTBTO network are up and running.

The more I learned about the increasing sophistication of infrasonic wave detection, the more convinced I became that the connection between infrasound and the fate of the Dyatlov hikers could only have been made fairly recently. As Bedard explained, it has only been in the last decade or so—dating from around the time of Bedard and Georges’ 2000 paper in

Physics Today

—that funding for infrasound science, and therefore a clearer understanding of its occurrence in nature, had gained any traction.

Could Lev Ivanov, working as a lead investigator in 1959, have come anywhere near to determining that infrasound had a role in the deaths of nine hikers in the Ural Mountains? Kármán vortex street aside, would Ivanov have known what infrasound was? Likely not. Nevertheless, Ivanov had done all he could with the information available to him at the time. When faced with a baffling set of circumstances that seemed to point to phenomena beyond his understanding, it’s not surprising that he would have entertained theories of “orbs” and UFOs.

Some thirty years later, after his retirement, Ivanov put his feelings about the case in writing. With glasnost and perestroika recently enacted, Ivanov was now free to discuss the case publicly. In his letter to the

Leninsky Put

newspaper, Ivanov took the chance to apologize to the hikers’ families for the secretive way in which the case had been handled: “I use this article to apologize to the families of the hikers, especially that of Dubinina, Thibault-Brignoles and Zolotaryov. At that time, I tried to do whatever I could, but, as lawyers call it, ‘compelling force’ was the ruling then and could only be overturned now.”

As for what had happened to the hikers, Ivanov alluded to the unknowable: “I had a clear idea of the sequence of their deaths from a thorough examination of their bodies, clothes and other data. Only the sky and its contents—with unknown energy beyond human understanding—were left out.”

While Ivanov had lacked the means to accurately explain a nearly incomprehensible event, he had used the resources and vocabulary available to him at the time. Ivanov’s written conclusion on May 28, 1959, that the hikers had been the victims of an “unknown compelling force” is one that has come to define the mystery surrounding the case. Though the phrase falls far short of an explanation, the conclusion had been strangely accurate. If infrasound generated by Kármán vortex street had indeed been responsible for the hikers’ leaving their tent that night—and, as a result, walking to their deaths—“unknown compelling force” was, at the time, as close as Lev Ivanov—or anyone—could have come to naming the truth.

28

The following is a re-creation of February 1, and the early morning

hours of February 2, using the hikers’ diary entries, weather

reports, physical evidence and expert scientific opinion

.

FEBRUARY 1–2, 1959

THE FIRST DAY OF FEBRUARY ARRIVES, BRINGING WITH

it one of the most carefree mornings of the hikers’ trip. The sky is overcast, the wind still, and the hikers linger in their tent over hot cocoa and breakfast. Afterward, pencils and paper come out, and, amid laughter and teasing, the friends draft issue #1 of their mock newspaper,

The Evening Otorten

. The paper is stocked with references and inside jokes accumulated over the course of their trip and years of friendship. When they are finished, an editorial at the top urges: “Let’s mark the XXIst session of the Communist Party with increased birth rate of hikers!” In engineering news, a review of a hiking sleigh designed by “Comrade Kolevatov” impishly concludes that while it is “perfect for riding in a train, in a truck and on a horse,” it is “not recommended for cargo freight on snow.” Above it, the science pages announce: “Scientific society leads vivid discussions about existence of snowman. Latest data show that snowmen dwell at northern Urals, around Otorten Mountain.” Whether by “snowmen,” the writers meant the abominable kind or a winking reference to themselves, only they could know.

With their high spirits lingering, the friends start to pack up camp, and in the process snap a few playful photographs outside the tent. Once the tent is rolled and stowed away, they begin construction of the

labaz

, the shelter that will hold the supplies for their return trip. There is no sense in hauling nonessentials— extra food, spare skis, boots—up Otorten Mountain. Though Georgy has difficulty parting with his mandolin, he knows that the trade-off of a lighter pack will be worth two days without music. The construction and packing of the

labaz

occupies most of the day, and it’s not until midafternoon that the skiers are finally on their way.

As the hikers move away from the protection of the woods, their smiling faces of that morning harden into expressions of sober concentration. The higher they climb, the more challenging the weather becomes, and by midday, their bodies are bowed single-file into the headwind. The photographers among them snap a few images of the group skiing into an ashen haze. With sunset arriving at 5:00

PM

, and the storm clearly worsening, it’s time to scout a campsite.

Around 4:30

PM

, the group pauses in an open area on the east-facing slope of a nameless mountain, known on maps only as “height 1,079” (what will later come to be named Holatchahl). Igor concludes that this is their spot. The slope isn’t steep enough for avalanches to be a concern, yet it is above the timberline and exposed to the elements, which is exactly the sort of challenge they are looking for. Ambitious hikers, after all, don’t earn the distinction of Grade III by playing it safe in the shelter of the trees. The spot also happens to be in direct sight of their destination, and at sunrise, after a quick breakfast, they will be better suited to quickly packing up and heading straight up Otorten Mountain. They make a note to themselves to photograph the site in the morning, as documentation for the hiking commission.