Dean and Me: A Love Story (16 page)

Read Dean and Me: A Love Story Online

Authors: Jerry Lewis,James Kaplan

Tags: #Fiction, #Non-Fiction, #Music, #Humour, #Biography

“Well, I do,” I said. “I’m absolutely sure of it. And I want to tell you something else. I know you’re not a hundred percent with the direction we’ve been going in lately. I understand that, and I understand why. It’s a tricky place we’re in now—I’m growing, you’re growing. Who knows where it’ll all end up? But I think we can still have some fun, Paul. I want you to try and remember how good it can be when we’re enjoying ourselves. Just give me this one movie, and I’ll try like hell to get back to the good times.”

It was all I could do to hold back the tears when he held out that big hand of his to shake. I wished we could have hugged, like in the old days—but then, as I had to keep reminding myself, it wasn’t the old days anymore.

Bad news travels fast, and word of the troubled shoot of

Three Ring Circus

was all over L.A. long before we returned from Phoenix. Our agent, Lew Wasserman, and our lawyer, Joe Ross, called us into the MCA offices to work things out. They were friendly but very firm: We had far too many commitments, they told us in no uncertain terms, to quarrel like school-boys. Tens of millions of dollars were on the line. There were our contracts with Wallis, NBC TV, radio, club bookings, and product endorsements.

“You’ve got to try to get along, guys,” Lew said. “For your own sakes, for everybody’s.”

“We’re doin’ okay,” Dean told him. “Right, Mr. Lupus?”

I could still see the coolness in his eyes. But that was all right, for now: Cool was better than cold.

Then a strange thing happened—or rather, a tragic thing with odd repercussions: Patti’s mom died. I’d been very close to Mary, and I was almost as devastated as my wife was.

Dean and Jeannie were at the wake and the funeral. When our family returned from the cemetery to the house, my partner and his wife came along—solid, soothing, sympathetic. While everyone was sitting around, speaking in quiet tones, Dean came up and asked if we could talk. “Of course we can,” I said. We went into my den and shut the door. We both admitted that we’d said some stupid things, and that we owed it to ourselves and our families to be the total pros that we knew we were. And when we were finished talking, we hugged.

Maybe, I thought, we could be OK just as long as we weren’t on a movie set....

That August, we were booked into Ciro’s for two weeks. We might have had our troubles with

Three Ring Circus

, yet as far as our fans were concerned, we were still very much at the top of our game. And the illustrious citizens of Hollywood had always been among our biggest fans.

Why was that? Film people knew what it was to make magic with a script, perfect photography, and brilliant editing. The fact that on stage Dean and I could work wonders with none of the above simply awed them.

The insanity started five weeks before we were to open: Everyone tried to book a table for opening night, and soon there were no seats left. I had made reservations for some of my closest friends.

Then one morning, with only two days left before our opening, I got out of bed and started to brush my teeth. When I looked in the mirror, I saw that my face was yellow to the gills. I phoned Dr. Levy, who made a house call (they still did that then). He told me I had hepatitis and the only way I’d be able to recover from it was complete bed rest. For eight weeks.

With the opening on top of us, there were two options: We could cancel, or Dean could go on alone. With the buildup we’d had, cancellation seemed out of the question. But I wasn’t sure how Dean felt about doing his first single in eight years.

He came to visit me at my house that afternoon. When he walked into my bedroom, I was ready—in a coolie hat and a Japanese waistcoat, with a record of “Japanese Sandman” playing on the phonograph. Dean almost fell on the floor laughing. After a minute or two, he settled down and sat on the edge of the bed, looking serious. “Listen, pally,” he said. “I talked with Dr. Levy. You gotta be careful with this thing, okay?”

“Listen, Paul—I may play one, but I’m not a fool,” I told him. “I’ll do whatever it takes to get better. You know how much I want to get back to work.”

“Good,” he said. He slapped me on the knee. “Now I’m gonna go play some golf.” And he started to walk out of the room.

“What? You’re about to do a single for the first time in eight years and you’re not planning a strategy so you don’t step on your balls?”

He stopped and looked at me, genuinely puzzled. “Strategy?” he said. Then he smiled. “Hey, as long as the seats are facing the stage, I’ll be fine!”

“You’re not going to rehearse?” I asked him.

“Rehearse what?” Dean said. “All’s I need is our music books. I pick a couple of tunes, throw in a couple of ideas that feel right, and have some fun. What are they gonna do? Kill me?”

“Would you like to share those ideas with me?” I said. “Maybe I can help.”

He was still smiling, but I thought I detected a long-suffering look in his eyes. “Help what?” he said. “It’s gonna be okay, I promise.” And with that, he blew me a kiss and left.

On opening night, I sent the following to Dean’s dressing room at Ciro’s: a case of Scotch, a case of Jack Daniel’s, two cases of Schweppes club soda, ten cartons of Camels, a case of his favorite red wine ... and bottle openers, tall glasses (the ones he liked that no one carried), and Old-Fashioned glasses. I had Paramount print a thousand cocktail napkins reading “DEAN MARTIN AND JERRY LEWIS,” with a big black X through my name.

I lay in bed as nervous as a cat, wondering, hoping, and praying a little. I expected not to hear anything until morning, since the show at Ciro’s didn’t break before midnight. But I was wrong. At 12:15, Jack Keller called me and said, “Can I come out to see you?”

“When?” I asked.

“Now!”

I figured if Jack Keller, who hated to drive, was ready to make the forty-minute trip out to my house in Pacific Palisades, it had to be important. I told him to come on out.

He walked into my bedroom at one A.M.—where, of course, I was ready for him in my Japanese outfit. Barely cracking a smile, Jack sat down on the opposite side of the room. If God Himself had told Jack that I wasn’t contagious (which I wasn’t), he’d still have sat across that room: Jack was a world-class hypochondriac.

“Was everything okay?” I asked him.

“Okay?” he said. “It was unbelievable! It was fantastic!”

I sat up straight in the bed. “Tell me!”

Keller says: “They introduce him, and the audience, who were in his corner from the get-go, all stand up as he walks on stage.... But instead of opening with a song, he signaled for quiet. You could’ve heard a pin drop. And Dean said, soft and serious, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, thank you for coming tonight, because it’s a very special night. A night I’ve been praying for, for the last eight years ... to be alone on stage without that goddamn noisy Jew.’

“The house came down,” Keller said. “Then, as the uproar died, Dean called to a stagehand. ‘Please,’ he said, ‘bring me that other item.’ The stagehand comes out with a mike stand and a mike, exactly like the one Dean has in front of him. ‘I can’t really feel comfortable,’ Dean says, ‘if he isn’t here next to me. So, all kidding aside, I’d like everyone here to say a silent prayer that my partner gets better very soon.’

“That audience applauded and whistled and stamped their feet,” Keller said. “It was electric! Then Dean did a song and broke it up with some silliness. Jack Benny stood up and asked him if he needed any help. And Dean says, ‘Sure, Jack, but no money!’ Jack looks around as only Jack can, then walks back to his seat with his head down, and the crowd screamed. Dean then went into a Martin and Lewis routine, breaking up his own song in your voice, and playing to the mike stand as if it was you.

“So help me God, Jerry, it was just like you were there, and Dean was never better....”

Talk about mixed emotions! I was bursting with pride and seething with jealousy at the same time.

He did so well!

part of me thought—while the other part of me thought,

How dare he do so well without

me

!

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

THE MARTIN AND LEWIS MOVIES WOULD NEVER HAVE DRAWN such big audiences without our wonderful leading ladies. There were so many, so talented in so many different ways—and, like Dean and me, so much better than the material they had to work with. Some of their names might surprise you: Did you know we appeared with Donna Reed? Agnes Moorehead? Anita Ekberg? But the dozens of lesser-known actresses who acted in our films all added immeasurably to our work. (And, despite rumors and innuendoes, Dean and I did

not

sleep with

all

of them—names will be made public upon request!)

However, to my vast regret, the one actress we never performed with was Marilyn Monroe—and how great she would have been in a Martin and Lewis picture.

Dean and I first met her when we were receiving the

Photoplay

magazine award as Best Newcomers of the Year (whatever the hell year it was) and Marilyn was the Best Female Newcomer. God, she was magnificent —perfect physically and in every other way. She was someone any man would just love to be with, not only for the obvious reasons but for her energy and perseverance and, yes, focus. She had the capacity to make you feel that she was totally engaged with whatever you were talking about. She was kind, she was good, she was beautiful, and the press took shots at her she didn’t deserve. They got on her case from day one—a textbook example of celebrity-bashing.

In the late fall of 1954, Marilyn’s marriage to Joe DiMaggio had just ended, and she badly needed friends—and laughs. Dean and I had seen her here and there over the years since the

Photoplay

awards, and when we invited her out for an after-work snack at Nate’n Al’s (then and now the best deli in Beverly Hills), she accepted instantly.

She had a delicious sense of humor—an ability not only to appreciate what was funny but to see the absurdity of things in general. The three of us huddled in a booth in a far corner of the restaurant, making fun of some of the late-night Hollywood regulars who drifted in and out. We laughed for a couple of hours, and then we drove her home in Dean’s blue Cadillac convertible. It was a warm November night; she was living, temporarily, in the Voltaire Apartments in West Hollywood. Marilyn asked us to have a drink with her, and we did. She hated to be alone, especially late at night, when she couldn’t sleep. She mentioned Joe a couple of times, but I think Dean and I both saw that there was a lot she couldn’t or didn’t want to talk about, so we tried to keep it light.

Soon it was close to two in the morning, and we had to get up early for work. (We were all on films at the time, with a six A.M. wake-up.) On the way out, I asked Marilyn if she would consider going to dinner with Dean and me one night that week.

“How about tonight?” she said.

“Tonight is perfect!” we said in unison.

Dean and I spent most of that day trying to figure out where the hell to take Marilyn Monroe for dinner. “I know!” I finally yelled. “Let’s go to Perino’s!”

It was the most elegant restaurant in L.A., on Wilshire Boulevard not too far from Slapsy Maxie’s. Great food, great service; strictly a wear-a-tie type of place. I had my secretary make reservations—for four, on the chivalrous assumption that Marilyn might bring someone. We were to meet at the restaurant, because she was shooting later than we were. We set the time for 8:30.

Dean and I left the set after work, and Christ, did we dress that night. I won’t even go into how much cologne was applied.

We stepped into Perino’s precisely at 8:30—and there at the waiting bar was Marilyn. Alone, sitting on a stool, and looking drop-dead, as always. Dean asked, “How come you’re alone? Where’s Milton?” It was well known that she had started seeing Milton Greene, the photographer. But Marilyn told us he had a family and had to be with them every now and then.

She said it with a slight note of sadness, but it was all Dean and I could do to keep the grins off our faces. We were seated in the center of this very open restaurant, with all eyes on ... guess who? She might as well have been having dinner with Price and Waterhouse! We ordered drinks and made lots of small talk. At one point, Marilyn teased: “Dean, don’t you think you’d make a perfect leading man for one of my films?”

Dean laughed and said, “Well, you know, every good screen team has a dog!”

I spoke right up in the Idiot’s voice: “I will not be a dog for anybody!”

Marilyn laughed, the captains laughed, the waiters laughed. And that’s what we did the whole night—laughed and laughed.

How amazing it is to think that it was only seven years after that night—both a short time and a lifetime—that Dean was cast as Marilyn’s love interest in

Something’s Got to Give

, for 20th Century Fox. By that time, poor Marilyn was falling apart. She was fired from the picture and, not long afterward, took her life. Christ, what a loss!

In that same eventful fall of ’54, Frank Sinatra invited Dean and me to visit the set of his latest movie,

The Man with the Golden Arm

. Based on the novel of the same name by Nelson Algren, the film is a harrowing story of a former card dealer and heroin addict named Frankie Machine struggling to get his act together after he’s released from prison. Frank played Frankie, and his performance was, I think, his greatest, even more spectacular than the work he’d done in

From Here to Eternity

two years earlier.

The Man with the Golden Arm

was being shot at the Goldwyn Studios, and the man in charge was Otto Preminger, the director from hell! He was good, but nasty to actors. The fact that I never worked with him probably added twenty years to my life.

Frank introduced us to Preminger when we walked onto the set, and the little director was quite cordial—he even told us that he’d caught our show at Slapsy Maxie’s and thought it was the best he had ever seen in a nightclub. We thanked him and stayed out of the way.

They were shooting a scene they’d rehearsed all morning—the climax of the movie, in which Frankie, who has slid back into addiction, goes through heroin withdrawal. Everyone was a little anxious, as people get when a big scene is about to explode. The set got extremely quiet. Prop men moved materials into place. The cinematographer checked last-minute light. Preminger called the roll, then cried, “Action!”

In the scene, Frank was in the corner of his bedroom, screaming at the top of his lungs as he underwent his horrific ordeal. Dean and I were standing directly beside the camera, and as close as we were, and as well as we knew that it was just a movie, we both had gooseflesh watching Frank’s incredible performance. It ran for the better part of four minutes, and was simply explosive. He hit every beat and every nuance. Then Preminger yelled “Cut!” and Frank got up off the floor and lit a cigarette. He walked toward the director to see how he liked it. “That was great, Frank,” Preminger said, “but we need one more take!”

Frank whirled around. “Another take?” he said. “For what, if that one was so good?”

I’m sure Preminger wasn’t surprised. Frank’s approach to a film never varied: He learned his dialogue, knew every scene by heart, rehearsed as much as the director wanted (though Preminger was the first filmmaker Frank ever rehearsed happily for), and was ready for the camera. He knew that any extra takes would lose spontaneity, and he was dead right. That’s why he was so good in everything he ever filmed. “One take and print it!” was his motto. It made directors a little testy, because it meant the actor was in charge, and the one thing that directors can’t stand is losing control. Frank walked back to his dressing room, calling Dean and me to follow, and we did.

Frank poured himself a tumbler of Jack Daniel’s, which he needed after that scene. We couldn’t stop telling him what a great job he’d done and how strongly it had affected us. “I knew it was perfect and that I’d never get it that way again!” he said. I knew exactly what Frank meant— I never wanted to do a comic scene twice. I would prepare it all day and shoot it once, strictly for the spontaneity, and in comedy that really is vital.

Preminger stopped by the dressing room and said (in the kind of voice that let me know he wanted something), “Frank, are you sure you want me to print that last take?”

Frank just looked at him while taking a sip of his Jack Daniel’s. “Uhhuh,” he said.

And that was that. When Dean and I saw the film in a theater, we knew Frank had been right. The scene knocked our socks off, and the audience’s, too. Frank definitely should have gotten an Oscar for that performance, but ultimately, I think, the film’s subject matter (which caused the Production Code to refuse it a seal of approval) was just too controversial for its time. Frank always did push the edges.

Not long after New Year’s, Hal Wallis and I traveled to New York to find an ingenue for the new Martin and Lewis movie,

Artists and Models

. It’s funny: As contentious as Wallis and I could be about business—and there were times I could have murdered that humorless skinflint—we could have a ball just hanging out. One thing we had in common was that we both loved to shop for shoes and clothes, and the New York trip featured plenty of that, as well as theatergoing. One cloudy Wednesday afternoon we were discussing what to do, and I said, “Let’s go to a musical—I love musicals!” I looked in the paper and my eyes immediately went to the listing for

The Pajama Game,

choreographed by my friend Bob Fosse.

But Wallis told me he had to meet with some lawyers and that I should go to the show myself. We would meet back at the Plaza for dinner. After dinner, Paramount had set up a cattle call in the hotel’s main ballroom so that Wallis and I could scout the talent and, we hoped, find the right girl for our movie.

I called the St. James Theater and easily arranged for a single ticket. I settled into my seat, not too happy about being alone (in fact, now that I think of it, this may have been the one and only time I ever went to the theater by myself). It made me feel all the more wistful to remember that the St. James was the very same theater to which Dean and I had brought June Allyson and Gloria De Haven to see

Where’s Charley?

six years earlier. I missed Dean—it was hard for me to admit how much I missed him.

Then it’s two o’clock, and there’s no downbeat and no curtain. And suddenly, a man walks to center stage and makes an announcement.

“Ladies and gentlemen—due to an ankle injury, the role played by Miss Carol Haney will be played this afternoon by her understudy, Miss Shirley MacLaine.”

There was a loud sigh of disappointment from the audience. Now, please understand: At this point, Shirley MacLaine was still Shirley Who? Carol Haney was the fabulous protégée of Gene Kelly, around whom Bob Fosse had built

The Pajama Game

’s showstopping “Steam Heat” number.

Oh well,

I thought.

I’m here. Let’s see.

Then the show went on, and the rest is Broadway legend, the kind of story line that, if it happened in a movie, most people would simply find too far-fetched to believe. Shirley came on and absolutely electrified me and everybody else in that audience. By the final curtain, we were all on our feet, yelling for her to come out again and again.

Then I ran out of the theater, hailed a cab, and went back to the Plaza. I wasn’t in my suite three minutes before Wallis called, saying he was back and had plans for us that evening. I said, “I’ll be right over!” I ran down the hall to his suite, banged on the door, and almost screamed in his face: “You have plans for tonight! I don’t think so! You must let me take you to the theater to see the girl we’re looking for!”

“Really,” he said with a smirk—as if to say, “

You

found the girl?”

I picked up the phone and asked for the hotel’s concierge. I told him I needed two orchestra seats for that night’s performance of

The Pajama

Game,

for Mr. Wallis and myself.

Wallis shook his head. “I’m not going to the theater tonight!” he said. “I’ve got other plans!”

I looked him in the eye. “If you trust my instinct,” I said, “you’ll change your plans.”

He pursed his lips, thought a second, and said, “All right, I’ll humor you.”

Humor?

I thought.

Where will he get it?

As we were riding to the theater in the limo, I was suddenly struck by a thought:

What if Carol Haney got better, and the girl I saw will never be

heard from again?

I was ready for the Intensive Care Unit until we got to the theater and picked up our tickets at the box office, where the sign said:

In Tonight’s Performance, Miss Carol Haney’s Role

Will Be Played by Miss Shirley MacLaine

I breathed a sigh of relief, and in we went.

At eleven P.M., Hal Wallis and I were on our feet along with the other 1,700 people in the St. James Theater. I thought Shirley had been terrific at the matinee—but that night she simply exploded on that stage. Not long afterward, Wallis gave her a screen test, then signed her to a contract, and my partner and I had a leading lady for

Artists and Models

, a lady who would go on to make a great career for herself, and whose path would cross again with Dean’s.

Often, others see us with the sharpest eyes. Then again, even the sharpest eyes can miss the whole truth. There’s a series of wonderfully vivid verbal snapshots in Shirley MacLaine’s Hollywood memoir, My

Lucky Stars

, of my partner and me during the shooting of

Artists and Models

. Shirley remembers what look like good times: The two of us going wild in the Paramount commissary, throwing food as Marlene Dietrich and Anna Magnani watch in horror, smearing butter all over the suit of production chief Y. Frank Freeman as Y. Frank, the courtliest of Southern gentlemen, sits in discreet shock (his real shock was yet to come). She recalls us racing golf carts around the studio lot, honking horns; jumping into strangers’ cars and screaming that we’re being kidnapped. She remembers the way Dean used to light a Camel with one of his gold cigarette lighters, blow out the flame, and throw the lighter out the window. These were all hijinks we’d been pulling for years, but Shirley was young and admiring, and witnessing them for the first time. It wouldn’t take her long to see the strain beneath the jolly surface.

So we had a leading lady; we also had a new director. The last half-dozen of our films, with the exception of

Three Ring Circus

, had all been under the watch of Norman Taurog or George Marshall. I had the utmost respect for Norman and George, but Wallis’s new discovery, Frank Tashlin, was a man I would come to revere.

Frank—or Tish, as I renamed him—started out as a newspaper cartoonist, then did some animation directing at Warner Brothers and other studios. A side job writing gags for Hal Roach’s low-budget comedies led to more gag-writing for live-action pictures (including a couple of the Marx Brothers’ and Bob Hope’s), then screenwriting, then directing. By the mid-1950s, Tish was a full-fledged movie director—the only important director ever to make the transition from animation to live action. But his background in cartoons always gave him a priceless instinct for outrageous comedy. (They said about him that he directed his cartoons like live-action comedies and his live-action comedies like cartoons.) He had an incomparable mind for the kind of humor that was right up our alley.

Unfortunately, Hal Wallis was standing halfway down the alley with a blackjack in his hand.

Wallis initially hired Tashlin not because Tish was a great comedic director but because

Artists and Models

was a story about comic books and cartoons. Hal Wallis was always a cut-and-dried fellow, and it was as cut-and-dried as that. Remember, Wallis knew as much about comedy as he did about atomic energy. But then, Hollywood deals always start with a smile and a handshake and a good deal of blindness about what’s going to happen next. I think that Tish never knew precisely what he was getting into.

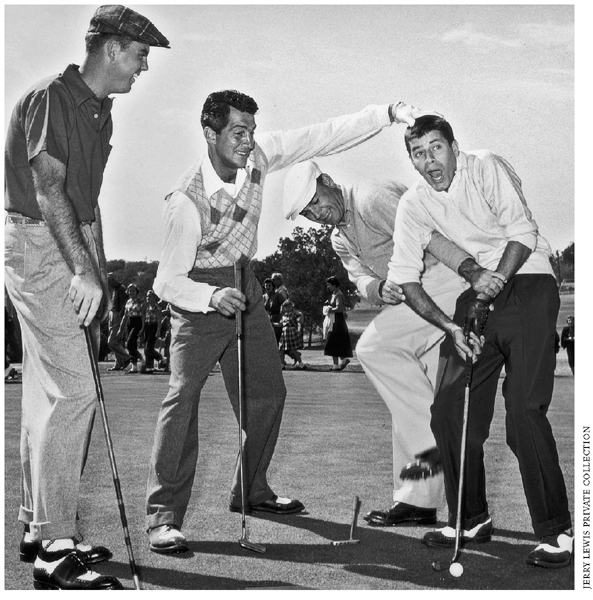

With Ben Hogan. They won’t let me mark my ball.

Frank and I liked each other right away. He was a big bruiser—six-three and 250-plus pounds; brush crew cut, mustache, and horn-rimmed glasses—and, for a guy who made his living out of nonsense, was surprisingly direct. His personality was what you might call extra-dry. He watched you, made his judgments, and spoke his mind only when he was good and goddamn sure what he wanted to say. He had a patient, long-suffering air about him. I amused Tish—I tried very hard to amuse him—but I think that what he saw in me was a perfect instrument for his ideas. I will always think of him as my great teacher.

Which didn’t mean he favored me over my partner. Not by a long shot. In fact,

Artists and Models

was a kind of liberation for Dean, especially after

Three Ring Circus

: In the new film (which Frank cowrote), Dean played my roommate and fellow wannabe comic-book writer, and he not only got as many lines as I did (a first) but (another first) had substantial comic material, as well as several terrific musical numbers.

Not surprisingly, for the first time in a while, there was zero tension on the set between the two of us. But at the time, I’m afraid, my ego was still ballooning. Frank Tashlin’s strategic decision to let me in on the technical aspects of the movie was creating not just a future filmmaker but a kind of monster. I spent much of the shoot engaged in range wars—or pissing matches, call them what you will—with Wallis over everything from his attitude toward the crew to how much of my off-camera time I could spend attending to Martin and Lewis business. I was locking horns with the Big Guy, ego versus ego. It was quite a tussle.

Meanwhile, Dean stood by smiling and practicing his golf swing. He was delighted with

Artists and Models

—and delighted to watch Wallis vs. Lewis from the sidelines.

The funny thing, though, is that on nearly every single issue, Wallis ultimately backed down. It wasn’t the power of my personality (though at the time I thought it was) so much as it was the power of the Martin and Lewis franchise. We were just too big a moneymaker for the producer to risk rocking the boat.

Instead, Wallis took out his ire on others.

One day toward the end of the shoot, Tashlin came onto the set looking like someone had rammed a twelve-inch pin in one of his ears and out the other. I went into his dressing room on Stage 5 and asked, “Anything I can do, Frank?”

“You’ve worked for Wallis long enough,” he said. “You know him, and if you want to help, find out how I can get out of my contract with him. I just will not allow him to diminish me the way he does. How can a man with so little knowledge about comedy...” And he proceeded to go into a tirade about what I understood all too well: the great Wallis’s utter tone-deafness when it came to humor on film.

I heard Tish out, then said, “Frank, if you’re really serious about getting out of your contract with Hal Wallis, there’s a very simple thing you can do.”

He blinked. “Simple? What’s simple about it?” he said.

“Listen, Frank,” I said. “Wallis loves cutting film better than seeing his own kid grow up. He believes himself to be the ultimate filmmaker—and in certain cases he is, but not with what

we do

. Now, if you write him a note saying you think he

cuts like a butcher

, I bet you’re out of your contract before he finishes reading it.”

Frank wrote what I suggested and sent it to Wallis’s office at about three P.M. Later, he phoned me at home to tell me that Wallis had called him at 5:15 to say he was out of his contract. Wallis didn’t want to work with him anymore!

Wallis cut

Casablanca

,

Fugitive from a Chain Gang

,

The Life of Emile Zola

, and

Jezebel

. He cut those films very dramatically and very well—and that’s the last nice thing I’ll say about Hal Wallis. He was a strange man. He had to win. He acted as if his very life depended on making his point. He justified all his actions with this pontification: “Great film can be put together by many men, but it is made by one man.” Without that one man, he felt, nothing could go forward. Maybe he was right, but he handled everything with such life-or-death conviction that he beat many around him into the ground. Yet away from his office he was a joy to be with. When he wasn’t behind that desk, he not only had a human side but a wonderful sense of humor. He could be generous almost to a fault. But behind that desk, he would cut your heart out if it saved him 50 cents.

Poor Frank. Free from his contract, he sat out our next (and also next-to-last) picture,

Pardners

. But then Wallis somehow sweet-talked him into returning to direct our last film, a total debacle all too aptly titled

Hollywood or Bust

. (The “or” in the title should have been replaced by an “and.”) After Dean and I broke up, Tish and I made a half-dozen pictures together (

The Geisha Boy

,

Rock-a-Bye-Baby

,

Cinderfella

,

It’s Only

Money

,

Who’s Minding the Store

, and

The Disorderly Orderly

). I continued to learn priceless lessons about film, and comedy, from him. But I think that the give-and-take of the movie business, and especially the stress of having to go up against people like Wallis, probably led to Frank’s much-too-early death, at age fifty-nine, in 1972.

Despite Wallis, and at the expense of Frank Tashlin’s nervous system,

Artists and Models

became what many regard as one of the best Martin and Lewis pictures. After the film wrapped, Dean and I took Dick Stabile, our twenty-six-man orchestra, and the rest of our staff and went on a two-week theatrical tour throughout the Midwest, then jumped east to the Boston Garden. We put all the pressure and contention and bitterness of the movie business behind us, and for seventeen charmed days in May of 1955, it felt just like old times....