Death from the Skies! (2 page)

Read Death from the Skies! Online

Authors: Ph. D. Philip Plait

Stepping up to the window, he stood on tiptoe to look around the yard.

What the—

Every tree was casting

two

distinct shadows. His morning routine now forgotten, Mark watched in amazement as, for every tree, one of the shadows appeared to be moving, circling around the base of the tree like fast-motion video of a sundial. Nose pressed to the window, he looked up into the sky, straining to see what could be causing this strange display.

What the—

Every tree was casting

two

distinct shadows. His morning routine now forgotten, Mark watched in amazement as, for every tree, one of the shadows appeared to be moving, circling around the base of the tree like fast-motion video of a sundial. Nose pressed to the window, he looked up into the sky, straining to see what could be causing this strange display.

Suddenly, from under the eave, it appeared as if the Sun itself were streaking across the sky. Dazzled, Mark’s eyes took a moment to adjust, but it was still not clear what he was seeing. There was a disk of intense white light moving across the sky, faster than an airplane. Could it be a meteor?

It appeared to descend slowly to the horizon as he watched. Then, in the blink of an eye, there was a soundless but all-encompassing flash, so bright his eyes watered. He winced in pain. When he was able to look again, the small bright disk was gone, replaced by a much larger smear of light, fanning up from the horizon. The heat from the thing was palpable, even through the window. It was like standing near a fireplace. As the smudge in the sky expanded, Mark noticed something even odder: did the tops of the trees look funny? Was that

smoke

rising from them . . . ?

smoke

rising from them . . . ?

The heat became intense. It began to dawn on Mark that he might be in trouble. As he stood there wondering what to do, a sudden and sharp earthquake jolted the house, knocking him to the floor. It was over quickly, and as he stood up, dazed, he felt the heat more strongly than before as it poured through his now-broken bathroom window. He thought the worst was over, but what he didn’t know was that a wave of pure sound and fury tearing through the atmosphere was pounding toward him at 700 miles per hour.

Too late, he saw the face of the shock wave bearing down on him like a tsunami ten miles high. A mighty thunderclap swept over his burning house, pulverizing it to dust with Mark still inside, and the time for decisions was over.

Everything under this wave of sound was stomped flat. Trees that were ablaze a moment before from the heat of the explosion were snuffed out, then torn into millions of splinters. The expanding ring of pressure, already dozens of miles across, screamed past the location of Mark’s disintegrated house and continued moving, greedily consuming buildings, trees, cars, people.

Before it was over, the shock wave circled the Earth twice. Seismographs from around the globe registered the event as an earthquake of enormous

scale, but no one paid attention to the scientific data for long. They were too busy struggling to survive.

METEORS AND METEOROIDS AND METEORITES, OH MY!scale, but no one paid attention to the scientific data for long. They were too busy struggling to survive.

The Earth sits in a cosmic shooting gallery, and the Universe has us dead in its crosshairs.

Consider this: the Earth is pummeled by twenty to forty

tons

of meteors every single day. Over the course of a year, that’s easily enough to fill a six-story office building with cosmic junk.

tons

of meteors every single day. Over the course of a year, that’s easily enough to fill a six-story office building with cosmic junk.

While that sounds like a lot, it’s really only a pittance compared to the size of the Earth, which is about a quintillion—a million million

million

—times bigger. But space is swarming with debris, and the Earth is constantly plowing through it.

million

—times bigger. But space is swarming with debris, and the Earth is constantly plowing through it.

The vast majority of this material is detritus, tiny bits of rock that burn up readily in our atmosphere. When you go out on a dark, clear night, you see these as “shooting stars,” what astronomers call

meteors.

You might be surprised to find out that even the brightest ones you’re likely to see are caused by tiny bits of fluff called

meteoroids,

no bigger than a grain of salt. Something as small as a pea would make a fantastically bright meteor—I once saw one that was so bright it lit up the sky and even left an afterimage on my eye. I stood transfixed for the two or three seconds it took to flash across the sky, but was just as shocked when I later calculated that the rock itself was probably no bigger than a grapefruit.

meteors.

You might be surprised to find out that even the brightest ones you’re likely to see are caused by tiny bits of fluff called

meteoroids,

no bigger than a grain of salt. Something as small as a pea would make a fantastically bright meteor—I once saw one that was so bright it lit up the sky and even left an afterimage on my eye. I stood transfixed for the two or three seconds it took to flash across the sky, but was just as shocked when I later calculated that the rock itself was probably no bigger than a grapefruit.

How can something so small get so bright? There are two factors to consider. You may be familiar with the first: compressing air heats it up. Think about how warm a bicycle pump gets after you use it—when the air is squeezed inside the pump, it gets hot and transfers that heat to the metal. You can actually burn yourself using a pump if you’re not careful. The more a gas is compressed, the hotter it gets. The second factor is the fantastic speed at which meteoroids travel. Most of them hit us at ten to twenty miles per second, and some come roaring in as fast as sixty miles per second! This is far, far faster than even a rifle bullet.

When something moving that rapidly enters our atmosphere, its velocity is translated into energy, which in turn is transferred to the air around it. As it screams through the upper atmosphere, a meteoroid rams the air violently—a rock moving at Mach 50 is going to compress the air a

lot.

The air gets squeezed so quickly and at such high pressure that it heats up thousands of degrees and starts to glow.

lot.

The air gets squeezed so quickly and at such high pressure that it heats up thousands of degrees and starts to glow.

As you can imagine, all that hot air is like a blast furnace. The meteoroid, traveling just a few inches behind that rammed air, feels that heat. It can’t last long in those conditions, and if it’s small it usually burns up in a matter of seconds. We see a bright glow, a streak across the sky that lasts for a moment or two, and then it’s gone, adding its nearly insignificant mass to the Earth’s.

To a stunned observer, a meteor looks like it’s traveling just over his head, but in reality the action is occurring fifty or more miles above the ground. At that height the air is very thin, yet still thick enough to stop small, dense particles. But what if the particle is bigger than a pea, or a grape, or a watermelon? What if it’s the size of, say, a couch, a car, a bus?

For a bigger object, things are very different. If it’s a few yards across, instead of simply burning up, that chunk of space debris gets squeezed by the air pressure as if it’s in a vise—the pressure can top out at over a thousand pounds per square inch at meteoric speeds. This pressure can flatten out the incoming object in a process called

pancaking

for obvious reasons. But a rock can only take so much of that before it crumbles and falls apart. Within seconds, instead of one big rock coming in, we now have hundreds or thousands of little ones, all still moving at velocities of several miles per second, and all dumping their energy into the air around them. They compress further, fracture, heat up, and so on . . . and within a fraction of a second we have a whole lot of rubble releasing a whole lot of heat all at once.

pancaking

for obvious reasons. But a rock can only take so much of that before it crumbles and falls apart. Within seconds, instead of one big rock coming in, we now have hundreds or thousands of little ones, all still moving at velocities of several miles per second, and all dumping their energy into the air around them. They compress further, fracture, heat up, and so on . . . and within a fraction of a second we have a whole lot of rubble releasing a whole lot of heat all at once.

This is, by definition, an explosion.

So medium-sized meteoroids blow up in the atmosphere. Again, this usually happens fairly high up, depending on how tough the meteoroid is; ones made of metal can take more punishment and penetrate deeper into our atmosphere, but may still explode many miles above the Earth’s surface. The energy involved is impressive: a rock only a meter across can explode with the force of hundreds of tons of TNT. In fact, military records indicate that such an explosion from an incoming chunk of rock is seen on average once a month!

Since meteoroids explode so high up in the atmosphere, you’d expect we’d be safe from things that size.

Well, not exactly. Under some conditions, the incoming rock may break up, but some chunks can survive. If the main mass slows enough before it explodes, then smaller fragments can slow even more without totally disintegrating. These can make it all the way to the ground. Metallic meteoroids have even more structural strength and can remain intact all the way down as well. If they do survive and impact the ground, they’re called

meteorites.

1

meteorites.

1

Small meteoroids that make it down to the ground usually aren’t moving terribly fast when they impact. In fact, their initial velocity is completely nullified by our air, leaving them to fall at what is called

terminal velocity.

It’s as if they were dropped off a tall building or from a balloon; they wind up impacting at maybe one or two hundred miles per hour. Scary, sure, but not

too

scary.

terminal velocity.

It’s as if they were dropped off a tall building or from a balloon; they wind up impacting at maybe one or two hundred miles per hour. Scary, sure, but not

too

scary.

Still, you wouldn’t want to get hit by a rock moving that fast. For comparison, they hit the ground faster than even a professional baseball player’s pitch. In November 1954, a woman named Ann Hodges from Sylacauga, Alabama, was actually hit by meteorite. It was fairly small, about the size of a brick and weighing just over eight pounds. It punched through her roof, bounced off a wooden radio cabinet, and smacked into her where she was lying on the couch, taking a nap that was rather rudely interrupted. Her hand and side were injured. She lived, but suffered one of the nastiest bruises in medical history.

This may be the earliest well-documented case of a meteorite damaging human property. But it wasn’t the last. With the advent of the video camera, it was inevitable that more and more spectacular meteors would be recorded.

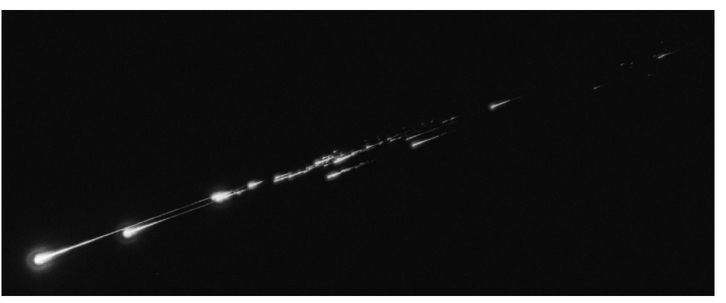

On October 2, 1992, a meteoroid the size of a school bus entered the Earth’s atmosphere. It created a huge fireball as it traveled northeast across the United States, and was witnessed by thousands of people—by a happy coincidence, it was on a Friday night during football season, so many proud parents were already running their video cameras, yielding excellent footage of the meteor. The rock broke apart as it ripped its way across the sky, and one of the pieces, roughly the size of a football, fell onto the trunk of a young woman’s car in Peekskill, New York. It left a hole in the back end of the car that looked, not surprisingly, exactly as if it had been caused by a rock dropped from a great height. One can imagine the difficulty the owner had getting her insurance company to pay for the damage.

These and other stories notwithstanding, in the end the Earth’s surface is big, and most meteorites are small. The odds of anyone’s getting hit by one are really very small, and the odds of being killed by one are even smaller.

As it burned its way through the Earth’s atmosphere, the Peekskill meteor was captured on dozens of home movie cameras. It broke into smaller chunks, one of which hit a woman’s car.

SARAH EICHMILLER AND THE

ALTOONA (PA) MIRROR

ALTOONA (PA) MIRROR

Still,

most

meteorites are small. Some aren’t.

SHALLOW IMPACTmost

meteorites are small. Some aren’t.

On June 30, 1908, the Earth and a smallish chunk of pretty weak rock found themselves at the same place at the same time.

The rock was probably seventy or so yards across. Its orbit intersected the Earth’s, and over time it was inevitable that the two objects would both be located at that intersection point simultaneously.

It came in over Siberia, in a remote region near the Podkamennaya Tunguska River. On that day, it entered the Earth’s atmosphere over Russia, traveling northwest. It plunged deeper into the air, and the increasing pressure put tremendous strain on the meteoroid. It broke apart, and each piece broke apart, and the cascade of rupture dumped a vast amount of energy into the air around it. The object exploded, releasing between three and twenty megatons of energy: the equivalent of three to twenty million tons of TNT, hundreds of times as much energy as the bomb dropped on Hiroshima thirty-seven years later.

The blast itself was seen by hundreds of witnesses (the Soviet Union even created a stamp based on what was seen), and the explosion registered on seismometers designed to detect earthquakes. People were knocked off their feet hundreds of miles away.

Despite the incredible event and the excitement it generated, a scientific expedition took years to mount. The region is unbelievably difficult to reach; in winter it’s forbidding at best (we’re talking Siberia after all), and in the summer the Tunguska region is a swamp, infested with mosquitoes. But eventually the site was reached, and what greeted those weary travelers had never been seen before.

As they approached the area of the explosion, the expedition members were shocked to see trees flattened like toothpicks for hundreds of square miles. Moreover, the trees were lying in parallel formations. Following the trail, the scientists came to a spot where the trees were all knocked over

radially,

like spokes on a bicycle wheel. Even weirder, the trees at ground zero were still standing, though totally denuded of branches and leaves. It’s hard to imagine what they must have felt upon seeing such an eerie sight.

radially,

like spokes on a bicycle wheel. Even weirder, the trees at ground zero were still standing, though totally denuded of branches and leaves. It’s hard to imagine what they must have felt upon seeing such an eerie sight.

No blast crater was ever found, nor (yet) any definitive debris from the rock. It exploded several miles above the ground, and totally vaporized. The air blast created a shock wave that knocked down those trees. The trees at the center were still standing because the blast wave slammed straight down into them; it takes sideways force to knock trees down. Nuclear airburst blasts during weapons tests of the 1950s and 1960s replicated the same pattern.

While the remote location of the explosion made it hard to study, it also meant few people were killed. Had the explosion occurred over Moscow or London, millions would have died within minutes, making this a very serious threat indeed. Still, the immediate effect from the explosion was localized. Probably no one more than a few dozen miles away was hurt.

Other books

Three by William C. Oelfke

Academy 7 by Anne Osterlund

[06] Slade by Teresa Gabelman

Do You Want to Know a Secret? by Mary Jane Clark

Blue and Alluring by Viola Grace

Giles Goat Boy by John Barth

Better Nate Than Ever by Federle, Tim

Gods and Soldiers by Rob Spillman

Reckoning by Kate Cary

Ecstasy by Bella Andre