Delphi Complete Works of Jerome K. Jerome (Illustrated) (Series Four) (387 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Jerome K. Jerome (Illustrated) (Series Four) Online

Authors: Jerome K. Jerome

How we all brag and bounce, and beat the drum and shout; and nobody believes a word we utter; and the people ask one another, saying:

“How can we tell who is the greatest and the cleverest among all these shrieking braggarts?”

And they answer:

“There is none great or clever. The great and clever men are not here; there is no place for them in this pandemonium of charlatans and quacks. The men you see here are crowing cocks. We suppose the greatest and the best of them are they who crow the loudest and the longest; that is the only test of their merits.”

Therefore, what is left for us to do, but to crow? And the best and greatest of us all, is he who crows the loudest and the longest on this little dunghill that we call our world!

Well, I was going to tell you about our clock.

It was my wife’s idea, getting it, in the first instance. We had been to dinner at the Buggles’, and Buggles had just bought a clock—”picked it up in Essex,” was the way he described the transaction. Buggles is always going about “picking up” things. He will stand before an old carved bedstead, weighing about three tons, and say:

“Yes — pretty little thing! I picked it up in Holland;” as though he had found it by the roadside, and slipped it into his umbrella when nobody was looking!

Buggles was rather full of this clock. It was of the good old-fashioned “grandfather” type. It stood eight feet high, in a carved-oak case, and had a deep, sonorous, solemn tick, that made a pleasant accompaniment to the after-dinner chat, and seemed to fill the room with an air of homely dignity.

We discussed the clock, and Buggles said how he loved the sound of its slow, grave tick; and how, when all the house was still, and he and it were sitting up alone together, it seemed like some wise old friend talking to him, and telling him about the old days and the old ways of thought, and the old life and the old people.

The clock impressed my wife very much. She was very thoughtful all the way home, and, as we went upstairs to our flat, she said, “Why could not we have a clock like that?” She said it would seem like having some one in the house to take care of us all — she should fancy it was looking after baby!

I have a man in Northamptonshire from whom I buy old furniture now and then, and to him I applied. He answered by return to say that he had got exactly the very thing I wanted. (He always has. I am very lucky in this respect.) It was the quaintest and most old-fashioned clock he had come across for a long while, and he enclosed photograph and full particulars; should he send it up?

From the photograph and the particulars, it seemed, as he said, the very thing, and I told him, “Yes; send it up at once.”

Three days afterward, there came a knock at the door — there had been other knocks at the door before this, of course; but I am dealing merely with the history of the clock. The girl said a couple of men were outside, and wanted to see me, and I went to them.

I found they were Pickford’s carriers, and glancing at the way-bill, I saw that it was my clock that they had brought, and I said, airily, “Oh, yes, it’s quite right; bring it up!”

They said they were very sorry, but that was just the difficulty. They could not get it up.

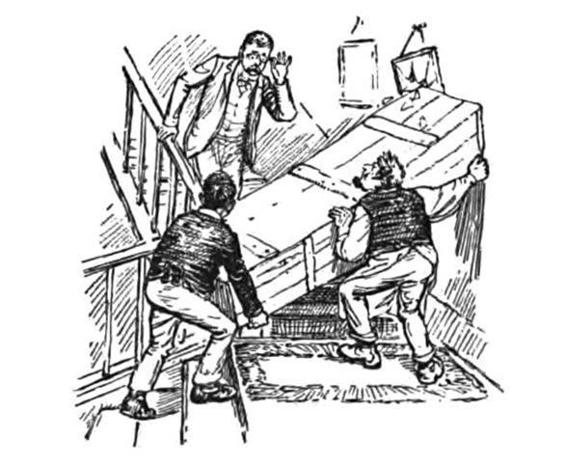

I went down with them, and wedged securely across the second landing of the staircase, I found a box which I should have judged to be the original case in which Cleopatra’s Needle came over.

They said that was my clock.

I brought down a chopper and a crowbar, and we sent out and collected in two extra hired ruffians and the five of us worked away for half an hour and got the clock out; after which the traffic up and down the staircase was resumed, much to the satisfaction of the other tenants.

We then got the clock upstairs and put it together, and I fixed it in the corner of the dining-room.

At first it exhibited a strong desire to topple over and fall on people, but by the liberal use of nails and screws and bits of firewood, I made life in the same room with it possible, and then, being exhausted, I had my wounds dressed, and went to bed.

In the middle of the night my wife woke me up in a great state of alarm, to say that the clock had just struck thirteen, and who did I think was going to die?

I said I did not know, but hoped it might be the next-door dog.

My wife said she had a presentiment it meant baby. There was no comforting her; she cried herself to sleep again.

During the course of the morning, I succeeded in persuading her that she must have made a mistake, and she consented to smile once more. In the afternoon the clock struck thirteen again.

This renewed all her fears. She was convinced now that both baby and I were doomed, and that she would be left a childless widow. I tried to treat the matter as a joke, and this only made her more wretched. She said that she could see I really felt as she did, and was only pretending to be light-hearted for her sake, and she said she would try and bear it bravely.

The person she chiefly blamed was Buggles.

In the night the clock gave us another warning, and my wife accepted it for her Aunt Maria, and seemed resigned. She wished, however, that I had never had the clock, and wondered when, if ever, I should get cured of my absurd craze for filling the house with tomfoolery.

The next day the clock struck thirteen four times and this cheered her up. She said that if we were all going to die, it did not so much matter. Most likely there was a fever or a plague coming, and we should all be taken together.

She was quite light-hearted over it!

After that the clock went on and killed every friend and relation we had, and then it started on the neighbours.

It struck thirteen all day long for months, until we were sick of slaughter, and there could not have been a human being left alive for miles around.

Then it turned over a new leaf, and gave up murdering folks, and took to striking mere harmless thirty-nines and forty-ones. Its favourite number now is thirty-two, but once a day it strikes forty-nine. It never strikes more than forty-nine. I don’t know why — I have never been able to understand why — but it doesn’t.

It does not strike at regular intervals, but when it feels it wants to and would be better for it. Sometimes it strikes three or four times within the same hour, and at other times it will go for half-a-day without striking at all.

He is an odd old fellow!

I have thought now and then of having him “seen to,” and made to keep regular hours and be respectable; but, somehow, I seem to have grown to love him as he is with his daring mockery of Time.

He certainly has not much respect for it. He seems to go out of his way almost to openly insult it. He calls half-past two thirty-eight o’clock, and in twenty minutes from then he says it is one!

Is it that he really has grown to feel contempt for his master, and wishes to show it? They say no man is a hero to his valet; may it be that even stony-face Time himself is but a short-lived, puny mortal — a little greater than some others, that is all — to the dim eyes of this old servant of his? Has he, ticking, ticking, all these years, come at last to see into the littleness of that Time that looms so great to our awed human eyes?

Is he saying, as he grimly laughs, and strikes his thirty-fives and forties: “Bah! I know you, Time, godlike and dread though you seem. What are you but a phantom — a dream — like the rest of us here? Ay, less, for you will pass away and be no more. Fear him not, immortal men. Time is but the shadow of the world upon the background of Eternity!”

EVERGREENS

THEY look so dull and dowdy in the spring weather, when the snow drops and the crocuses are putting on their dainty frocks of white and mauve and yellow, and the baby-buds from every branch are peeping with bright eyes out on the world, and stretching forth soft little leaves toward the coming gladness of their lives. They stand apart, so cold and hard amid the stirring hope and joy that are throbbing all around them.

And in the deep full summer-time, when all the rest of nature dons its richest garb of green, and the roses clamber round the porch, and the grass waves waist-high in the meadow, and the fields are gay with flowers — they seem duller and dowdier than ever then, wearing their faded winter’s dress, looking so dingy and old and worn.

In the mellow days of autumn, when the trees, like dames no longer young, seek to forget their aged looks under gorgeous bright-toned robes of gold and brown and purple, and the grain is yellow in the fields, and the ruddy fruit hangs clustering from the drooping boughs, and the wooded hills in their thousand hues stretched like leafy rainbows above the vale — ah! surely they look their dullest and dowdiest then. The gathered glory of the dying year is all around them. They seem so out of place among it, in their somber, everlasting green, like poor relations at a rich man’s feast. It is such a weather-beaten old green dress. So many summers’ suns have blistered it, so many winters’ rains have beat upon it — such a shabby, mean, old dress; it is the only one they have!

They do not look quite so bad when the weary winter weather is come, when the flowers are dead, and the hedgerows are bare, and the trees stand out leafless against the grey sky, and the birds are all silent, and the fields are brown, and the vine clings round the cottages with skinny, fleshless arms, and they alone of all things are unchanged, they alone of all the forest are green, they alone of all the verdant host stand firm to front the cruel winter.

They are not very beautiful, only strong and stanch and steadfast — the same in all times, through all seasons — ever the same, ever green. The spring cannot brighten them, the summer cannot scorch them, the autumn cannot wither them, the winter cannot kill them.

There are evergreen men and women in the world, praise be to God! Not many of them, but a few. They are not the showy folk; they are not the clever, attractive folk. (Nature is an old-fashioned shopkeeper; she never puts her best goods in the window.) They are only the quiet, strong folk; they are stronger than the world, stronger than life or death, stronger than Fate. The storms of life sweep over them, and the rains beat down upon them, and the biting frosts creep round them; but the winds and the rains and the frosts pass away, and they are still standing, green and straight. They love the sunshine of life in their undemonstrative way — its pleasures, its joys. But calamity cannot bow them, sorrow and affliction bring not despair to their serene faces, only a little tightening of the lips; the sun of our prosperity makes the green of their friendship no brighter, the frost of our adversity kills not the leaves of their affection.

Let us lay hold of such men and women; let us grapple them to us with hooks of steel; let us cling to them as we would to rocks in a tossing sea. We do not think very much of them in the summertime of life. They do not flatter us or gush over us. They do not always agree with us. They are not always the most delightful society, by any means. They are not good talkers, nor — which would do just as well, perhaps better — do they make enraptured listeners. They have awkward manners, and very little tact. They do not shine to advantage beside our society friends. They do not dress well; they look altogether somewhat dowdy and commonplace. We almost hope they will not see us when we meet them just outside the club. They are not the sort of people we want to ostentatiously greet in crowded places. It is not till the days of our need that we learn to love and know them. It is not till the winter that the birds see the wisdom of building their nests in the evergreen trees.

And we, in our spring-time folly of youth, pass them by with a sneer, the uninteresting, colourless evergreens, and, like silly children with nothing but eyes in their heads, stretch out our hands and cry for the pretty flowers. We will make our little garden of life such a charming, fairy-like spot, the envy of every passer-by! There shall nothing grow in it but lilies and roses, and the cottage we will cover all over with Virginia-creeper. And, oh, how sweet it will look, under the dancing summer sun-light, when the soft west breeze is blowing!