Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) (1306 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) Online

Authors: SIR ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE

“The shells ploughed the men out of their shallow trenches as potatoes are turned from a furrow,” says an officer. Two companies of the 8th Somersets, however, seem to have lost direction and wandered off to Hill 70, where they were involved in the fighting of the Fifteenth Division. Two companies of the Yorks and Lancasters were also ordered up in that direction, where they made a very heroic advance. A spectator watching them from Hill 70 says: “Their lines came under the machine-guns as soon as they were clear of the wood. They had to lie down. Many, of course, were shot down. After a bit their lines went forward again and had to go down again. They went on, forward a little and then down, and forward a little and then down, until at last five gallant figures rose up and struggled forward till they, too, went down... The repeated efforts to get forward through the fire were very fine.”

These four companies having left, there remained only two of the Somersets and two of the Yorks and Lancasters in the wood. Their comrades in advance had in the meantime become involved in a very fierce struggle in the Bois Hugo. Here, after being decimated by the machine-guns, they met and held for a time the full force of the German attack. The men of Yorkshire and of Lincolnshire fought desperately against heavy masses of troops, thrown forward with great gallantry and disregard of loss. For once the British rifle-fire had a chance, and exacted its usual high toll. “We cut line after line of the enemy down as they advanced.” So rapid was the fire that cartridges began to run low, and men were seen crawling up to their dead comrades to ransack their pouches.

The enemy was dropping fast, and yet nothing could stop him. Brigadier Nicholls walked up to the firing line with reckless bravery and gave the order to charge. Bayonets were actually crossed, and the enemy thrown back. The gallant Nicholls fell, shot in the thigh and stomach, and the position became impossible. The Lincolns had suffered the appalling loss of all their officers and 500 men. The Yorkshires were in no better case. The survivors fell back rapidly upon the supports.

Fortunately, these were in close attendance. As the remains of the Lincolns and the West Yorkshires, after their most gallant and desperate resistance to the overwhelming German attack, came pouring back with few officers and in a state of some confusion from the Bois Hugo and over the Lens-Hulluch road, the four companies under Majors Howard and Taylor covered their retreat and held up for a time the German swarms behind them, the remains of the four battalions fighting in one line.

One party of mixed Lincolns and Yorkshires held out for about seven hours in an advanced trench, which was surrounded by the enemy about eleven, and the survivors, after sustaining very heavy losses—”the trench was like a shambles” — did not surrender until nearly six o’clock, when their ammunition had all been shot away. The isolation of this body was caused by the fact that their trenches lay opposite the south end of the Bois Hugo. The strong German attack came round the north side of the wood, and thus, as it progressed, a considerable number of the Lincolns and some of the West Yorks, still holding the line upon the right, were entirely cut off. Colonel Walter of the Lincolns, with Major Storer, Captains Coates and Stronguist, and three lieutenants, are known to have been killed, while almost all the others were wounded. A number of our wounded were left in the hands of the Germans. There is no doubt that the strength of the German attack and the resistance offered to it were underrated by the public at the time, which led to the circulation of cruel and unjust rumours.

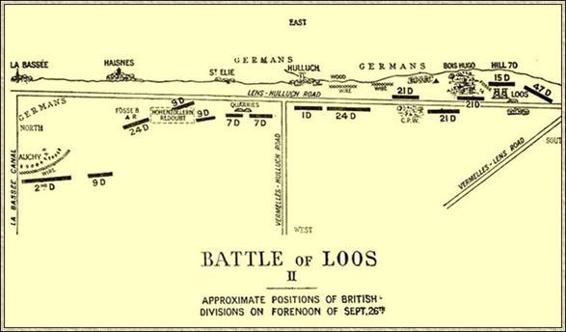

Battle of Loos 2

The 64th Brigade (Gloster) was in support some little distance to the right rear of the 63rd, covering the ground between the Lens-Hulluch road and Loos. About noon a message was received by them to the effect that the 63rd was being very strongly pressed, and that help was urgently needed. The 14th Durham Light Infantry was moved forward in support, and came at once under heavy fire, losing its Colonel (Hamilton), 17 officers, and about 200 men. The 15th Durham Light Infantry was then thrown into the fight, and sustained even heavier losses. Colonel Logan, 18 officers, and 400 men were killed or wounded. About one o’clock the two Durham battalions were in the thick of the fight, while Captain Liebenrood, machine-gun officer of the 64th Brigade, did good work in keeping down the enemy fire. The two battalions of Yorkshire Light Infantry (9th and 10th) were held in reserve. About 2:30 the pressure upon the front of the 63rd Brigade had become too great, and both it and the two Durham battalions were driven back. Their resistance, however, seems to have taken the edge off the dangerous counter-attack, for the Germans did not come on past the line of the road and of the Chalk Pit Wood.

It will be remembered that when the two advanced brigades of the Fifteenth Division established themselves in hastily-dug trenches upon the western slope of Hill 70, they threw back their left flank obliquely down the hill towards Fosse

The losses. It may be noted that the losses of the two supporting divisions were about 8000 men. Their numbers in infantry were about equal to the British troops at Waterloo, and their casualties were approximately the same. Mention has already been made of the endurance of Mitford’s 72nd Brigade. The figures of the 63rd and their comrades of the 64th are little inferior. Of these troops more than 40 per cent of the rank and file, 65 per cent of their officers, and 75 per cent of their commanders lay upon the field of battle. When one recollects that 33 per cent was reckoned a high rate of loss by the greatest authorities upon warfare, and when one remembers that these were raw troops fighting under every discomfort and disadvantage, one feels that they have indeed worthily continued the traditions of the old Army and founded those of the new. There were isolated cases of unordered retirement, but in the main the regiments showed the steadiness and courage which one would expect from the good North-country stock from which they came.

The divisional artillery of the Twenty-first Division had come into action in the open behind the advancing infantry, and paid the price for their gallant temerity. The 94th Brigade E.F.A. lost especially heavily, eight of its guns being temporarily put out of action. Major Dobson of this brigade was among the killed. It is to be feared that the guns did not always realise the position of the infantry, and that many of the 64th Brigade especially were hit by their own shrapnel. Such painful incidents seem almost inseparable from modern warfare. The artillery kept its place, and afterwards rendered good service by supporting the advance of the Guards.

Whilst this advance and check had taken place in the centre and right centre of the British position, the London Division, upon the extreme right, was subjected rather to bombardment than to assault. A heavy fall of asphyxiating shells was experienced a little after

point d’appui

for a rally and reorganisation. Men of the Twenty-first Division re-formed upon this line, and the battle was soon re-established. This re-establishment was materially helped by the action of the 9th and 10th Yorkshire Light Infantry battalions previously mentioned of the Twenty-first Division, who had become a divisional reserve. These two battalions now advanced and gained some ground to the east of Loos on the enemy’s left flank. It may be mentioned that one of these battalions was ordered to discard its packs in order to ease the tired soldiers, and that on advancing from their trenches these packs were never regained. Their presence afterwards may have given the idea that equipment had been abandoned, whereas an actual order had been obeyed. The movement covered the reorganisation which was going on behind them. One small detachment under Captain Laskie of the 10th Y.L.I, did especially good work. The Yorkshiremen were aided by men of the Northumberland Fusiliers of the 62nd Brigade, who held on to the trenches to the east of Loos. A cavalry detachment from Campbell’s 6th Cavalry Brigade, under Campbell himself, had also appeared about 4 P.M. as a mobile reserve and thrown itself into Loos to strengthen the defence.

The evening of this day, September 26, found the British lines contracted as compared with what they had been in the morning. The Forty-seventh Division had, if anything, broadened and strengthened their hold upon the southern outskirts of Loos. The western slope of Hill 70 was still held in part. Thence the line bent back to the Loos-La Bassée road, followed the line of that road for a thousand yards, thence onwards to near the west end of the village of Hulluch, and then as before. But the exchanges would seem to have been in favour of the Germans, since they had pushed the British back for a stretch of about a mile from the Lens-Hulluch road, thus making a dent in their front. On both sides reserves were still mustering. The Guards’ Division had been brought up by Sir John French, and were ready for operations upon the morning of the 27th, while the Twenty-eighth Division was on its way. The Germans, who had been repeatedly assured that the British Army extension was a bluff, and that the units existed only upon paper, must have found some food for thought as the waves rolled up.

IX. THE BATTLE OF LOOS

From September 27 to the End of the Year

Loss of Fosse 8 — Death of General Thesiger — Advance of the Guards — Attack of the Twenty-eighth Division — Arrival of the Twelfth Division — German counter-attacks — Attack by the Forty-sixth Division upon Hohenzollern Redoubt — Subsidiary attacks — General observations — Return of Lord French to England

THE night of September 26 was a restless and tumultuous one, the troops being much exhausted by their long ordeal, which involved problems of supply unknown in any former wars. The modern soldier must be a great endurer as well as an iron fighter.

The Germans during the night were very pushful in all directions. Their reserves are said to have been very mixed, and there was evidence of forty- eight battalions being employed against the British line, but their attacks were constant and spirited. The advanced positions were, however, maintained, and the morning of the 27th found the attackers, after two days of incessant battle, still keeping their grip upon their gains.

The main part of the day began badly for the British, however, as in the early morning they were pushed off Fosse 8, which was an extremely important point and the master-key of the whole position, as its high slag-heap commanded Slag Alley and a number of the other trenches to the south of it, including most of the Hohenzollern Redoubt. The worn remains of the 26th Brigade were still holding the pit when morning dawned, and the units of the 73rd Brigade (Jelf) were in a semicircle to the east and south of it. These battalions, young troops who had never heard the whiz of a bullet before, had now been in close action for thirty-six hours, and had been cut off from all supplies of food and water for two days. Partly on account of their difficult tactical position, and partly because they were ignorant of how communications are kept up in the trenches, they had become entirely isolated. It was on these exhausted troops that the storm now broke. The northern unit consisted of the 7th Northamptons, whose left wing seems to have been in the air. Next to them were the 12th Royal Fusiliers. There had been several infantry attacks, which were repulsed during the night. Just at the dawn two red rockets ascended from the German lines, and at the same moment an intense bombardment opened upon Fosse 8, causing great loss among the occupants. It was at this time that General Thesiger, Commander of the Ninth Division, together with his Staff- Major, Burney, was killed by a shell. Colonel Livingstone, Divisional C.O. of Engineers, and Colonel Wright, of the 8th Gordons, were also hit. In the obstinate defence of the post the 90th Company R.E. fought as infantry, after they had done all that was possible to strengthen the defences.

A strong infantry attack had immediately followed the bombardment. They broke in, to the number of about a thousand, between the Northamptons and Fusiliers. By their position they were now able to command Fosse 8, where the 9th Sussex had been, and also to make untenable the position of the 27th Brigade, which occupied trenches to the south which could be enfiladed. In “The First Hundred Thousand” will be found a classical account of the straits of these troops and their retirement to a safer position. General Jelf telephoned in vain for the support of heavy guns, and even released a carrier pigeon with the same urgent request. Seeing that Fosse 8 was lost, he determined to hold on hard to the Hohenzollern Redoubt, and lined its trenches with the broken remains of his wearied brigade. The enemy at once attacked with swarms of well- provided bombers in the van, but were met foot to foot by the bombers of the 73rd Brigade, who held them up. The 26th Brigade endeavoured to counter-attack, but were unable to get forward against the machine-guns, but their bombers joined those of the English brigade and did splendid work. The ground was held until the troops, absolutely at the limit of human endurance, were relieved by the 85th Brigade of the Twenty-eighth Division, as will be described later. The trench held by the Sussex was commanded from above and attacked by bombers from below, so that the battalion had a very severe ordeal. Lieutenant Shackles defended a group of cabarets at one end of the position until he and every man with him was dead or wounded. Having taken that corner, the Germans bombed down the trench. Captain Maclvor with thirty men on that flank were all killed or wounded, but the officer leading the bombers was shot by Captain Langden and the position saved. Nineteen officers and 360 men fell in this one battalion.

“We gained,” said one of them, “two Military Crosses and many wooden ones.” It had been an anxious day for all, and most of all for General Jelf, who had been left without a staff, both his major and his captain having fallen.

Up to mid-day of the 27th the tide of battle had The set against the British, but after that hour there came into action a fresh force, which can never be employed without leaving its mark upon the conflict. This was the newly-formed division of Guards (Lord Cavan), consisting of the eight battalions which had already done such splendid service from Mons onwards, together with the newly-formed Welsh Guards, the 3rd and 4th Grenadier Guards, the 2nd Coldstream, and the 2nd Irish.

On September 25 the Guards reached Noeux-les-Mines, and on September 26 were at Sailly-la-Bourse. On the morning of the 27th they moved forward upon the same general line which the previous attack had taken that is, between Hulluch on the left and Loos on the right and relieved the two divisions which had suffered so heavily upon the previous day. The general distribution of the Guards was that the 1st Brigade (Fielding), consisting of the 2nd Grenadiers, 2nd and 3rd Coldstream, and 1st Irish, were on the left. They had taken over trenches from the First Division, and were now in touch upon their left with the Seventh Division. On the right of the 1st Guards’ Brigade was the 2nd (Ponsonby), consisting of the 3rd Grenadiers, 1st Coldstream, 1st Scots, and 2nd Irish. On their right again, in the vicinity of Loos, was the 3rd Brigade (Heyworth), the 1st and 4th Grenadiers, 2nd Scots, and

At 2:30 P.M. the British renewed their heavy bombardment in the hope of clearing the ground for the advance. There is evidence that upon the 25th the enemy had been so much alarmed by the rapid advance that they had hurriedly removed a good deal of their artillery upon the Lens side. This had now been brought back, as we found to our cost. At four o’clock the heavy guns eased off, and the two brigades of Guards (2nd and 3rd) advanced, moving forward in artillery formation that is, in small clumps of platoons, separated from each other.

The 2nd Irish were given their baptism of fire by being placed in the van of the 2nd Brigade with orders to make good the wood in front. The 1st Coldstream were to support them. Advancing in splendid order, they reached the point without undue loss, and dug themselves in according to orders. As they lay there their comrades of the 1st Scots passed on their right under very heavy fire in salvos of high-explosive shells, and carried Fosse 14 by storm in the most admirable manner, while the Irish covered them with their rifle-fire. Part of the right-hand company of the Irish Guards got drawn into this attack and rushed forward with the Scots. Having taken Fosse 14, this body of men pushed impetuously forward, met a heavy German counter-attack, and were driven back. Their two young leaders, Lieutenants Clifford and Kipling, were seen no more. The German attack came with irresistible strength, supported by a very heavy enfilade fire. The remains of the Scots Guards were driven with heavy losses out of Fosse 14, and both they and the Irish were thrown back as far as the line of the Loos-Hulluch road.

The remains of the shaken battalions were joined by two companies of the 2nd Coldstream and reformed for another effort. In this attack of the 2nd Brigade upon Fosse 14, the Scots were supported by two companies of the 3rd Grenadiers, the other two being in general reserve. These two companies, coming up independently somewhat later than the main advance, were terribly shelled, but reached their objective, where they endured renewed losses. The officers were nearly all put out of action, and eventually a handful of survivors were brought back to the Chalk Pit Wood by Lieutenant Ritchie, himself severely wounded.

Captain Alexander, with some of the Irish, had succeeded also in holding their ground in the Chalk Pit Wood, though partly surrounded by the German advance, and they now sent back urgently for help. A fresh advance was made, in the course of which the other two companies of Coldstreamers pushed forward on the left of the wood and seized the Chalk Pit. It was hard soil and trenching was difficult, but the line of the wood and of the pit was consolidated as far as possible. A dangerous gap had been left between the 1st Coldstream, who were now the extreme left of the 2nd Brigade, and the right of the 1st Brigade. It was filled up by 150 men, hastily collected, who frustrated an attempt of the enemy to push through. This line was held until dark, though the men had to endure a very heavy and accurate shelling, against which they had little protection. In the early morning the 1st Coldstream made a fresh advance from the north-west against Fosse 14, but could make no headway against the German fire. The line of Chalk Pit Wood now became the permanent line of the Army.

The 3rd Brigade of Guards had advanced at the same time as the 2nd, their attack being on the immediate right on the line of Fosse 14 and Hill 70. It may indeed be said that the object of the 2nd Brigade attack upon Fosse 14 was very largely to silence or engage the machine-guns there and so make it easier for the 3rd Brigade to make headway at Hill 70. The Guardsmen advanced with great steadiness up the long slope of the hill, and actually gained the crest, the Welsh and the 4th Grenadiers in the lead, but a powerful German redoubt which swept the open ground with its fire made the summit untenable, and they were compelled to drop back over the crest line, where they dug themselves in and remained until this section of the line was taken over by the Twelfth Division.

The Guards had lost very heavily during these operations. The 2nd Irish had lost 8 officers and 324 men, while the 1st Scots and 1st Coldstream had suffered about as heavily. The 3rd Brigade had been even more severely hit, and the total loss of the division could have been little short of 3000. They continued to hold the front line until September 30, when the 35th and 36th Brigades of the Twelfth Division relieved them for a short rest. The Fifteenth Division had also been withdrawn, after having sustained losses which had probably never been excelled up to that hour by any single division in one action during the campaign. It is computed that no fewer than 6000 of these gallant Scots had fallen, the greater part upon the blood-stained slope and crest of Hill 70. Of the 9th Black Watch little more than 100 emerged safely, but an observer has recorded that their fierce and martial bearing was still that of victors.

The curve of the British position presented a perimeter which was about double the length of the arc which marked the original trenches. Thus a considerably larger force was needed to hold it, which was the more difficult to provide as so many divisions had already suffered heavy losses.

The French attack at Souchez having come to a standstill, Sir John French asked General Foch, the Commander of the Tenth Army, to take over the defence of Loos, which was done from the morning of the 28th by our old comrades of Ypres, the Ninth Corps. During this day there was a general rearrangement of units, facilitated by the contraction of the line brought about by the presence of our Allies. The battle-worn divisions of the first line were withdrawn, while Bulfin’s Twenty-eighth Division came up to take their place.

The Twenty-eighth Division, of Ypres renown, had reached Vermelles in the early morning of Monday the 27th — the day of the Guards’ advance. The general plan seems to have been that it should restore the fight upon the left half of the battlefield, while the Guards’ Division did the same upon the right. General Bulfin, the able and experienced Commander of the Twenty-eighth, found himself suddenly placed in command of the Ninth also, through the death of General Thesiger. The situation which faced him was a most difficult one, and it took cool judgment in so confused a scene to make sure where his force should be applied. Urgent messages had come in to the effect that the defenders of Fosse 8 had been driven out, that as a consequence the whole of the Hohenzollern Redoubt was on the point of recapture, and that the Quarries had been wrested from the Seventh Division by the enemy. A very strong German attack was surging in from the north, and if it should advance much farther our advance line would be taken in the rear. It was clear that the Twenty-eighth Division had only just arrived in time. The 85th Brigade under General Pereira was hurried forward, and found things in a perilous state in the Hohenzollern Redoubt, where the remains of the 26th and 73rd Brigades, driven from Fosse 8 and raked by guns from the great dump, were barely holding on to the edge of the stronghold. The 2nd Buffs dashed forward with all the energy of fresh troops, swept the enemy out of the redoubt, pushed them up the trench leading northwards, which is called “Little Willie” (“Big Willie” leads eastward), and barricaded the southern exit. Matters were hung up for a time by the wounding both of General Pereira and of his Brigade-Major Flower, but Colonel Roberts, of the 3rd Royal Fusiliers, carried on. The Royal Fusiliers relieved the Buffs, and the 2nd East Surrey took over the left of the line.