Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) (1424 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) Online

Authors: SIR ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE

Early on the morning of November 3 the enemy showed clear signs of having had enough, and was withdrawing along the whole front, closely pursued by mounted troops and by infantry. Curgies and Saultain were taken, and the line rapidly extended. On November 4 the pace accelerated, and the crossings of the River Aunelle were forced, the Eleventh Division having a sharp fight at Sebourg. On November 5 the Belgian frontier was crossed and the villages of Mesaurain, Boisin, and Angre were occupied. There was some fighting on this day, the 168th Brigade having a sharp skirmish at Angre. Three tanks of British pattern were captured during the day. On November 6 the Grande Aunelle River had to be crossed, and the Germans made a resistance which at one time was both strenuous and successful. There was a great deal of gas, and all troops had to wear their masks. The Eleventh Division was unable to reach the river on account of the long open slope down which any advance must be made. The Fifty-sixth Division got across south of Angre, and reached the high ground to the east, the 2nd London and London Rifle Brigade in the lead. The former battalion was heavily counter-attacked in the Bois de Beaufort and was driven back to the river, while the London Rifle Brigade also suffered heavy casualties from machine-gun fire from Angre. Forty men of the 2nd Londons were entirely cut off but held on in a deep ditch in the wood, and were surrounded by the enemy. None the less they managed to cut their way out and rejoin their battalion.

On the left of the attack the Kensingtons and London Scottish crossed the river and got possession of Angre. They found themselves involved in a very fierce fight, which swayed backwards and forwards all day, each side attacking and counter-attacking with the utmost determination. Twice the Londoners were driven back and twice they regained their objectives, ending up with their grip still firm upon the village, though they could not retain the high ground beyond. Late at night, however, the 168th Brigade established itself almost without opposition upon the ridge.

On November 7 the opposition had wilted away and the Twenty-second Corps advanced with elements of three divisions in front, for the naval men were now in line on the left, “on the starboard bow of the Second Canadians,” to quote their own words. The river was crossed on the whole front and a string of villages were occupied on this and the following days. The rain was pouring down, all bridges had been destroyed, the roads had been blown up, and everything was against rapidity of movement. None the less the front flowed ever forward, though the food problem had become so difficult that advanced troops were supplied by aeroplane. The 16th Lancers had joined the Australian Light Horse, and the cavalry patrols pushed far ahead. Bavay was taken on November 10, and the Corps front had reached one mile east of Villers St. Ghislain when, on November 11, the “cease-fire” was sounded and the white flag appeared.

The general experience of the Twenty-second Corps during these last weeks of the war was that the German rearguards consisted mainly of machine-guns, some of which were fought as bravely as ever. The infantry, on the other hand, were of low morale and much disorganised. Need for mounted troops who could swiftly brush aside a thin line and expose a bluff was much felt. The roads were too muddy and broken for the cyclists, and there was no main road parallel with the advance. Owing to his machine-guns and artillery the enemy was able always to withdraw at his own time. 3200 prisoners had been taken by the Twenty-second Corps in the final ten days.

In dealing with the advance of Horne’s First Army we have examined the splendid work of the Canadian Corps and of the Twenty-second Corps. We must now turn to the operations of Hunter-Weston’s Eighth Corps on the extreme north of this Army, linking up on the left with the right of Birdwood’s Fifth Army in the neighbourhood of Lens. Up to the end of September, save for local enterprises, neither the Eighth Division on the right nor the Twentieth on the left had made any serious movement. The time was not yet ripe. At the close of September, however, when the line was all aflame both to the south and in Flanders, it was clear that the movement of the British Armies must be a general one. At that date the Eighth Division extended its flank down to the Scarpe, where it was in touch with the Forty-ninth Division, forming the left of Godley’s Twenty-second Corps. Before effecting this change Heneker, on September 21, carried out a spirited local attack with his own division, by which he gained important ground in the Oppy and Gavrelle sectors. It was a hard fight, in which the 2nd Berks had specially severe losses, but a considerable area of important ground was permanently gained.

Early in October General Heneker proceeded to carry out an ambitious scheme which he had meditated for some time, and which had now received the approbation of his Corps Commander. This was an attack by his own division upon the strong Fresnes — Rouvroy line, to the north-east of Arras. His plan was to make a sudden concentrated assault upon the south end of this formidable deeply-wired line, and then to work upwards to the north, avoiding the perils and losses of a frontal advance. This enterprise was begun at

This strong triple system of the Hindenburg type was attacked in the early morning of October

From this period the advance on this front was a slow but steady triumphant progress. By the end of October the Eighth Division had gone forward more than thirty miles since it started, and had captured thirty-five towns and villages, including Douai, Marchiennes, and St. Amand. Beyond being greatly plagued by murderous explosive traps, 1400 of which were discovered, and being much incommoded by the destruction of roads and bridges and by the constant canals across its path, there was no very serious resistance. Great floods early in November made the situation even more difficult. On November 5 the Eighth Division was relieved by the Fifty-second, and quitted the line for the last time.

This splendid division has had some injustice done to it, since it was the one Regular division in France in 1914 which was somewhat invidiously excluded from the very special and deserved honours which were showered upon “the first seven divisions.” But even in 1914 it had done splendid work, and as to its performance in the following years, and especially in 1918, when it was annihilated twice over, it will live for ever, not only in the records of the British Army, but in that of the French, by whose side it fought in the direst crisis and darkest moment of the whole campaign. There were no further movements of importance on the front of the Eighth Corps, and the completion of their history covers the whole operation of Horne’s First Army in this final phase of the war. It was indeed a strange freak of fate that this general, who commanded the guns of the right wing at Mons in that momentous opening battle, should four and a half years later be the commander who brought his victorious British Army back to that very point.

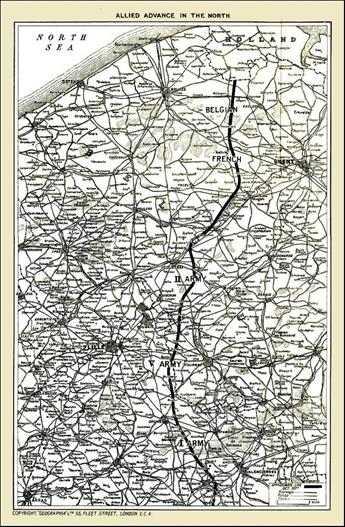

Allied Advance in the North

XI. OPERATIONS OF THE SECOND AND FIFTH ARMIES

September 28 — November 11

King Albert in the field — Great Belgo-Franco-British advance — The last act on the old stage — The prophet of 1915 — Renewed advance — Germans desert the coast — Relief of Douai and Lille — The final stage of the subsidiary theatres of war.

WE have followed the operations of the three southern British Armies from the first blow on August 8 — a blow which Ludendorff has stated made him surrender the last hope of ultimate victory — through all their uninterrupted progress of victory until the final armistice. We shall now turn to the northern end of the British line, where the two remaining Armies, the Fifth in the Nieppe district and the Second in the area of Ypres, were waiting impatiently for their share in the advance. Flanders was a convalescent home for divisions, and there was not a unit there which was not stiff with half-healed wounds, but these Armies included many of the grand old formations which had borne the stress of the long fight, and they were filled with the desire to join in the final phase. Their chance came at last, though it was a belated one.

There were many indications in the third week of July that the Germans had planned one of their great attacks upon the front of Birdwood’s Fifth Army in the Nieppe district. The succession of blows which rained upon Hindenburg’s line in the south made it impossible, however, for him to attempt a new offensive. There was considerable activity along the British line, and a constant nibbling which won back by successive ventures much of the ground which had been gained by the Germans in April. Early in July the Fifth Division, forming the left unit of the Fifth Army, advanced from the edge of Nieppe Forest, where they had lain since their return from Italy, and gained a stretch of ground — the first sign of the coming recoil in the north. To the left of them lay De Lisle’s Fifteenth Corps, which moved forward in turn, effecting a series of small but important advances which were eclipsed by the larger events in the south, but reacted upon those events, since they made it impossible for the Germans to detach reinforcements. On July 19 the Ninth Division with a sudden spring seized Meteren with 453 prisoners, while on the same date the First Australian Division occupied Merris to the south of it. On August 9 the movement spread farther south, and the Thirty-first Division took Vieux Berquin. There was a slow steady retraction of the German line from this time onwards, and a corresponding advance of the British. On August 30 the ruins of Bailleul passed into the hands of the Twenty-ninth Division. On September 1 Neuve Eglise was submerged by the creeping tide, while on the 3rd Nieppe also was taken. Finally on September 4 two brigades of the Twenty-ninth Division, the 88th under Freyberg and the 86th under Cheape, captured Ploegsteert by a very smart concerted movement in which 250 prisoners were taken. Up to this date De Lisle’s Fifteenth Corps had advanced ten miles with no check, and had almost restored the original battle line in that quarter — a feat for which M. Clemenceau awarded the General special thanks and the Legion of Honour.

All was ready now for the grand assault which began on September 28 and was carried out by the Belgians and French in the north and by Plumer’s Second British Army in the south. The left of this great force was formed by nine Belgian and five French infantry divisions, with three French cavalry divisions in reserve. The British Army consisted of four corps: Jacob’s Second Corps covering Ypres, Watts’ Nineteenth Corps opposite Hollebeke, Stephens’ Tenth Corps facing Messines, and De Lisle’s Fifteenth Corps to the south of it. The divisions which made up each of these Corps will be enumerated as they come into action. To complete the array of the British forces it should be said that Birdwood’s Fifth Army, which linked up the First Army in the south and the Second in the north, consisted at that date of Haking’s Eleventh and Holland’s First Corps covering the Armentieres — Lens front, and not yet joining in the operations. The whole operation was under the command of the chivalrous King of the Belgians, who had the supreme satisfaction of helping to give the

coup de grâce

to the ruffianly hordes who had so long ill-used his unfortunate subjects.

The operations of the Belgians and of the French to the north of the line do not come within the scope of this narrative save in so far as they affected the British line. General Plumer’s attack was directed from the Ypres front, and involved on September 28 two Corps, the Second on the north and the Nineteenth on the south. The order of divisions from the left was the Ninth (Tudor) and the Twenty-ninth (Cayley), with the Thirty-sixth Ulsters (Coffin) in reserve. These constituted Jacob’s Second Corps, which was attacking down the old Menin Road. South of this point came the Thirty-fifth (Marindin) and the Fourteenth Division (Skinner), with Law-ford’s Forty-first Division in support. These units made up Watts’ Nineteenth Corps. On the left of Jacob’s was the Belgian Sixth Division, and on the right of Watts’ the British Tenth Corps, which was ordered to undertake a subsidiary operation which will presently be described. We shall now follow the main advance.

This was made without any bombardment at

On September 29 the advance was resumed with ever-increasing success all along the line. The Scots of the Ninth Division, working in close liaison with the Belgians, got Waterdamhoek, and detached one brigade to help our Allies in taking Moorslede, while another took Dadizeele, both of them far beyond our previous limits. The Twenty-ninth Division still pushed along the line of the Menin Road, while the Thirty-sixth Ulsters fought their way into Terhand. In this quarter alone in front of Jacob’s Second Corps fifty guns had been taken. Meanwhile the Nineteenth Corps on the right was gaining the line of the Lys River, having taken Zandvoorde and Hollebeke; while the Thirty-fourth and Thirtieth Divisions of the Tenth Corps were into Wytsohaete and up to Messines, and the Thirty-first Division of the Fifteenth Corps was in St. Yves. In these southern sectors there was no attempt to force the pace, but in the north the tide was setting swiftly eastwards. By the evening of September 29 Ploegsteert Wood was cleared and Messines was occupied once again. The rain had started, as is usual with. Flemish offensives, and the roads were almost impossible; but by the evening of October 1 the whole left bank of the Lys from Comines southward had been cleared. On that date there was a notable hardening of the German resistance, and the Second Corps had some specially fierce fighting. The Ulsters found a tough nut to crack in Hill 41, which they gained twioe and lost twice before it was finally their own. The Ninth Division captured Ledeghem, but was pushed to the west of it again by a strong counter-attack. Clearly a temporary equilibrium was about to be established, but already the advance constituted a great victory, the British alone having 5000 prisoners and 100 guns to their credit.

In the meantime Birdwood’s Fifth Army, which had remained stationary between the advancing lines of the Second Army in Flanders and of the First Army south of Lens, began also to join in the operations. The most successful military prophet in a war which has made military prophecy a by-word, was a certain German regimental officer who was captured in the La Bassée district about 1915, and who, being asked when he thought the war would finish, replied that he could not say when it would finish, but that he had an opinion as to where it would finish, and that would be within a mile of where he was captured. It was a shrewd forecast based clearly upon the idea that each side would exhaust itself and neither line be forced, so that a compromise peace would become necessary. For three years after his dictum it still remained as a possibility, but now at last, within six weeks of the end, La Bassée was forced, and early in October Ritchie’s Sixteenth Division, the Fifty-fifth West Lancashire Territorials, and the Nineteenth Division under Jeffreys, were all pressing on in this quarter, with no very great resistance. South of Lens the Twentieth Division (Carey) had been transferred from the left of the First Army to the right of the Fifth, and this had some sharp fighting on October 2 at Mericourt and Acheville. Both north and south of the ruined coal capital the British infantry was steadily pushing on, pinching the place out, since it was bristling with machine-guns and very formidable if directly attacked. The Twelfth Division (Higginson), fresh from severe service in the south and anaemic from many wounds, occupied

The attack in the north had been held partly by the vile weather and partly by the inoreased German resistance. The Twenty-ninth Division had got into Gheluvelt but was unable to retain it. The enemy counter-attacks were frequent and fierce, while the impossible roads made the supplies, especially of cartridges, a very serious matter. The worn and rutted Menin Road had to conduct all the traffic of two Army Corps. No heavy artillery could be got up to support the weary infantry, who were cold and wet, without either rest or cover. Time was needed, therefore, to prepare a further attack, and it was October 14 before it was ready. Then, as before, the Belgians, French, and British attacked in a single line, the advance extending along the whole Flemish front between the Lys River at Comines and Dixmude in the north, the British section being about ten miles from Comines to the Menin — Roulers Road.

Three British Corps were engaged, the Second (Jacob), the Nineteenth (Watts), and the Tenth (Stephens), the divisions, counting from the south, being the Thirtieth, Thirty-fourth, Forty-first, Thirty-fifth, Thirty-sixth, Twenty-ninth, and Ninth. The three latter divisions, forming the front of Jacob’s Corps, came away with a splendid rush in spite of the heavy mud and soon attained their immediate objectives. Gulleghem, in front of the Ulsters, was defended by three belts of wire, garnished thickly with machine-guns, but it was taken none the less, though it was not completely occupied until next day. Salines had fallen to the Twenty-ninth Division, and by the early afternoon of October 15 both divisions were to the east of Heule. Meanwhile Cuerne and Hulste had been cleared by the Ninth Division, the 1st Yorkshire Cyclists playing a gallant part in the former operation. The net result was that in this part of the line all the troops had reached the Lys either on the evening of September 15 or on the morning of September 16.

The advance in the south had been equally successful, though there were patches where the resistance was very stiff. The 103rd Brigade on the left of the Thirty-fourth Division enveloped and captured Gheluwe and were afterwards held up by field-guns firing over open sights until they were taken by a rapid advance of the 5th Scottish Borderers and the 8th Scottish Rifles. The 102nd Brigade made a lodgment in the western outskirts of Menin, which was fully occupied on the next day, patrols being at once pushed across the Lys. These were hard put to it to hold on until they were relieved later in the day by the Thirtieth Division. Wevelghem was cleared on the 15th, and on the 16th both the Ninth and Thirty-sixth Divisions established bridge-heads across the river, but in both cases were forced to withdraw them. In the north the Belgians had reached Iseghem and Cortemarck, while the French were round Roulers. By the night of October 15 Thourout was surrounded, and the Germans on the coast, seeing the imminent menace to their communications, began to blow up their guns and stores preparatory to their retreat. On October 17 the left of the Allied line was in Ostend, and on the 20th it had extended to the Dutch border. Thus after four years of occupation the Germans said farewell for ever to those salt waters of the west which they had fondly imagined to be their permanent advanced post against Great Britain. The main tentacle of the octopus had been disengaged, and the whole huge, perilous creature was shrinking back to the lairs from which it had emerged.