Dennis Wheatley - Duke de Richleau 07 (74 page)

Read Dennis Wheatley - Duke de Richleau 07 Online

Authors: The Second Seal

General Hoffmann smiled

and stroked the dark stubble on his chin. “My assistants and I worked all

through the night. It is completed.”

Turning back to the map,

he went on quickly, “Now,

Herrschaft

,

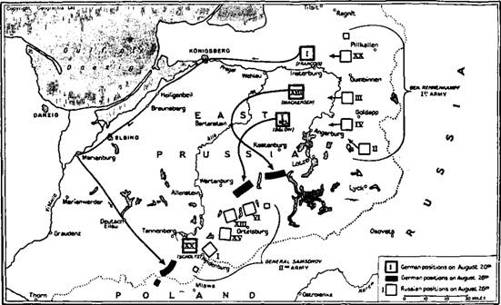

for the broader picture. You will see that the Grand Duke has divided his

forces into two Army Groups. His 1st and 2nd Armies, under General Jilinski,

are opposed to us on this front. His 4th, 5th, 3rd and 8th, in that order, are

massed under General Ivanov from opposite Przemysl down to the Rumanian border.

But, observe,

Herrschaft,

in the Polish salient he has nothing but covering troops and the skeleton of a

9th Army which is reported to be forming behind Warsaw. If General von

Hötzendorf strikes east, he will come up against the main forces of General

Ivanov’s southern Army Group. But if he strikes north, he will be opposed only

by the flank of the 4th Army. By adopting the latter course he can be of the

greatest possible assistance to us, and, I hope, by the time he reaches Warsaw,

we to him. For we shall no longer be facing east ourselves, but south; and

immediately we have defeated Samsonov’s army we can march straight on to form a

junction with your forces.”

De Richleau saw at once what this brilliant staff

officer was up to. Such a man would never have disclosed his plans so fully to

his allies unless he thought that by doing so he could get something out of

them. He wanted the Austrians to attack north so that, although distant, their

line of advance would threaten Samsonov’s rear, and possibly cause him to break

off his battle with the re-deployed German 8th Army. What Hoffmann had

deliberately refrained from pointing out was that immediately this 8th Army was

relieved from Samsonov’s pressure in the south, it would have to turn north

again

GENERAL

HOFFMANN’S REDEPLOYMENT OF THE GERMAN EIGHTH ARMY AFTER GUMBINNEN

to face a renewed attack by Rennenkampf. But the Duke

naturally refrained from saying so.

Lanzi only stroked his

beautiful beard with an air of profound wisdom, and remarked: “Then you think,

Herr General

that in a week or so’s time you may

after all be in a position to co-operate with us?”

“Certainly,

Herr Oberste Baron”

replied the German blandly. “I,

therefore, suggest that you should send a signal to your C.-’n-C., urging him

to attack in a northerly direction at once, and follow it yourself as soon as

possible, in order to explain matters to him in detail.”

That suited the Duke, but

did not suit Lanzi. Since the previous evening he had been happily toying with

the idea of once again having a romp with little Mitzi Muller. As a city, he

hated Berlin; but he occasionally had to pass through it on his way to shoot

boar with minor German royalties, and whenever he put in a night with her there

she gave him a very good time. He was now most loath to forgo the salacious

entertainment that this depraved young person provided. But he had sense enough

to realize that even his amiable old crony, the Archduke Frederick, might kick

if he lingered on his journey in such circumstances as the present; so he said:

“We will send the

telegram, and after this talk with you,

Herr General

, I am prepared to make it a very

strong one. But I shall not start back until to-morrow. By then we may have

received a satisfactory reply. If not, we shall at least know for certain whether

General von Fran

ç

ois

has succeeded in disengaging his Corps, and I shall then be in a better

position to advise my

C. in C.

further.”

Concealing his annoyance,

De Richleau told the General about the letter he had to deliver to von Moltke,

and said that he thought: he ought now to proceed at once to Aix-la-Chapelle

with it. But Hoffmann vetoed that by a request that could hardly be refused.

“Since you are going to

Main Headquarters, I should be glad if you would take a dispatch for me. I

shall not have it ready until to-morrow morning, as I must wait for to-night’s

situation reports before I can complete it. But your own letter can be of no

great urgency, or you would have been sent direct to Aix-la-Chapelle; so it won’t

matter in the least if you don’t deliver it for a day or two. Also, it is

certain that, when you get there, they will question you about the situation

here and, if you do not leave until to-morrow morning, you will be able to give

them more up to date information.”

So the matter was decided;

and, unwittingly, the Duke and the Baron had been among the first to be made

aware of one of the most remarkable feats in military history. Overnight.

General Hoffmann had taken the battle out of his

C. in C.

’s hands and, in a few hours,

re-disposed the whole of the 8th Army, directing it on Tannenberg where, one

week later, it was to win immortal glory.

Daring the remainder of

the 21st, nothing of apparent importance happened, but on the morning of the

22nd a piece of news came in that electrified the Headquarters. Von Prittwitz

had been sacked. In his place a combination had been appointed that was to

become world famous. General Hindenburg was to be

C. in C.

, with General Ludendorff as his

Chief of Staff. About both, romantic and spectacular stories were soon running

round.

Old Hindenburg had

specialized in East Prussia. He knew every coppice and every marsh in it, but

he had reached the age limit and been retired three years earlier. On the

outbreak of war, he had immediately offered his services, but there were so

many younger generals available that it had not been thought worth while to use

him, even for training troops. For three weeks he had been sitting daily at his

usual café in Hanover in a civilian suit, eating out his heart. Now, out of the

blue the call had come—not to an administrative job, not to inspect new

formations, or train reservists, but to be Commander-in-Chief Eastern Front and

save his imperilled Fatherland from invasion.

Ludendorff was known to

be one of the most brilliant officers of that talented and exclusive

organization, the

Stabs Corps.

So dynamic was he, that his superiors had sent him the previous year to cool

his heels for a while as a Commander of an Infantry brigade. But he had been

re-posted as Deputy Quartermaster-General to the German spearhead which, after

invading Belgium, had on the night of the 6th of August been given the task of

capturing Liege. In the darkness the advancing columns had lost their way among

the enemy forts, become mixed up, and finally halted in hopeless confusion. Out

of the night, Ludendorff had appeared upon the scene, taken command of all the

forces he could collect, found the right road, led the troops personally into

the city and, at dawn, demanded and received the surrender of the citadel with

its entire garrison.

These two were now on the

way east as fast as a special train could bring them. A telegram had already

been received from Ludendorff. It suspended von Prittwitz, ordered the Corps

Commanders to act independently until further instructions, and required all

the principal staff officers with 8th Army Headquarters to meet him and the new

C. in C.

back at Marienburg on

the eastern arm of the Vistula.

It was now six days since

the Duke had left Vienna and, fearing that sooner or later his presence at

Przemysl must come to the ears of Major Ronge, he was extremely anxious to

proceed with his plan for disappearing; so, on hearing the news, he at once

went to General Hoffmann and asked for the dispatch.

The General replied that,

in view of the change in command, he no longer intended to send his dispatch as

it stood. He added that he felt confident that the new

C. in C.

would move up to Wartenburg as soon

as he was informed of the situation, and that as De Richleau would certainly be

asked about East Prussia when he reached Main Headquarters, it was essential

that he should remain until he had heard General Hindenburg’s views.

That left De Richleau no

alternative but to make a moonlight flitting; so, reluctant as he was to remain

there a moment longer than he positively had to, he decided that, rather than

take such a drastic step after all had gone so well, it would be better to stay

on for another day, in the hope that doing so would enable him to leave openly.

Having secured the

agreement of the Corps Commanders to continue the movements he had prescribed,

General Hoffmann and a number of others hurriedly set off in the train that was

kept in the siding near the house, leaving only the junior officers behind to

function now as an advance headquarters. But that evening a new visitor

arrived, and no secret was made of the fact that he was Chief of the German

Secret Intelligence Corps.

He was a tall dark man,

wore Colonel’s uniform and was named Walter Nicolai. He announced that all his

Intelligence arrangements were working admirably in the west, so he had thought

the time ripe to check up on those for the Eastern Front. During dinner he gave

a glowing account of the German wheel into Belgium, and the news that the

serious fighting which had been reported along the Western Front from the

morning of the 20th on, had now developed into the first great battle between

the French and German armies. He had innumerable figures on the tip of his

tongue and said that 2,000,000 Germans were now engaged against 1,300,000

Frenchmen, so there could be no possible doubt that within a few weeks the

Fatherland would destroy the French army and force its remnants to surrender.

As had been the case at

Przemysl, De Richleau was known as Colonel Count Königstein, and everybody

referred to him by that name, with the one exception of old Lanzi, who

persisted in calling him ‘Duke’. When they were sitting in the ante-room after

dinner this anomaly aroused the curiosity of Colonel Nicolai, and Lanzi

smilingly explained the matter. Thereupon, the Intelligence Chief gave the Duke

a rather queer look, and said:

“How strange. I had an

idea that the Duc de Richleau was a Frenchman who had taken British

nationality. I feel sure I remember reading a report about his having been in

London last spring, and our people got the idea that he was mixed up in some

way with the Committee of Imperial Defence.”

It was a horrid moment

for the Duke, but he managed to keep his glance, and the hand that held his

cigar, quite steady, as a glib lie came without effort to his lips:

“That must have been my

rascally cousin, up to his tricks again. When he thinks he can get away with

it, he has the impudence to use my title. For some years he has been living in

the United States, and as I have never been there I have had no opportunity of

showing him up as an impostor. From what you say, I suppose he must have been

on a visit to London.”

Colonel Nicolai seemed

quite satisfied with the explanation, but De Richleau was badly shaken. He

decided that night that, whatever happened, he must get away from Wartenburg

the following day. But first thing next morning he learned that Hindenburg and

Ludendorff were on their way up from Marienburg, so he decided not to burn his

boats until the evening; by which time he hoped to have secured the sanction of

one of them to his leaving.

They arrived that

afternoon; Hindenburg big, square-headed, impressive; Ludendorff, plump,

double-chinned and, as the Kaiser said of him, ‘with a face like a sergeant’.

General Hoffmann looked tired, but happy. He had feared to be made the whipping

boy for von Prittwitz’s blunders, and replaced. But his tremendous

tour de force

on the night of the 20th had earned

him high praise from his new Chiefs. Not only were he and his staff confirmed in

their appointments, but Ludendorff had not altered a single one of his

brilliant re-dispositions for the coming battle of Tannenberg.