Desert Divers (2 page)

Authors: Sven Lindqvist

Seventy thousand years ago, the Sahara began to turn green again, with trees and grass. But the same cold snap that made the temperature mild and pleasant in the Sahara turned Central Europe into a treeless tundra and covered North Europe with inland ice for over fifty thousand years.

Twelve thousand years ago, when the inland ice had retreated from Sweden, the Sahara was still green. But about six thousand years BC, a dry spell began and lasted for fifteen hundred years. Then the rains came back for a thousand years. A new dry period occurred between 3300 and 2500 BC. The next rainy period was short – only five hundred years. The present dry period began in about 2000 BC, so has lasted for four thousand years.

Very small changes in the world’s average temperature –

only a degree or two – create an ice age in North America or a desert in the Sahara. At this moment, as I arrive, it is one of the hottest periods over the last million years. From a geological point of view, the apparent eternity of the Saharan desert is merely an episode between two European ice ages.

Where the road comes down to the sea there is a small fishing harbour, with screaming gulls swarming around it. The white foaming breakers roll in against sedimentary rock resembling clumps of plasticine. Along the edge of the plateau, often ten or so metres above the surface of the sea, lone fishermen walk with their long fishing rods. Poverty-stricken gatherers of brushwood and roots search for fuel for the night’s fire.

People on this coast made their first contact with Europe when the Portuguese Henrique el Navegador sailed past in 1441. His men went ashore and captured twelve nomads to take with them.

Thus the manhunt began. The small fishing villages along the coast had nothing but stones and spears with which to defend themselves. In 1443, Eannes de Azurara relates:

Some were drowned in the sea, others hid in their cabins, yet others tried to bury their children in the sand in order to return later to fetch them. But Our Lord God, who rewards everything well done, decided as compensation for the hard work our men had done

in His service that day to allow them to conquer their enemies and take 165 prisoners, men, women and children, not counting those killed or who killed themselves.

At the end of the 1400s, when Portugal and Spain divided up the world between them, the Spaniards were given the Saharan coast, as it lay close to the Spanish Canary Isles. But by the time four hundred Spaniards stepped ashore to take possession of the area, the Saharans had had time to organize resistance. Only a hundred Spaniards escaped with their lives. The hunt for slaves continued all through the 1500s, but for almost four hundred years the Saharans managed to prevent Europeans from gaining a foothold on the coast.

At the tip of the Cap Juby headland there is no archipelago, only one small island.

A Scot called Donald MacKenzie opened a store there in 1875. He called it the North West Africa Company and successfully traded cloth, tea and sugar for wool, leather and ostrich feathers.

The Sultan of Morocco disliked the competition. In 1895, he bought the store for £50,000 and closed it.

MacKenzie was also a thorn in the flesh of the Spanish traders on the Canary Isles, where he had a base. They wanted to take over his profitable caravan trade and exploit the rich coastal fishing grounds. In 1884, they sent men to the Sahara

and built a fort on the next headland, the Dakla Peninsula, and called it Villa Cisneros.

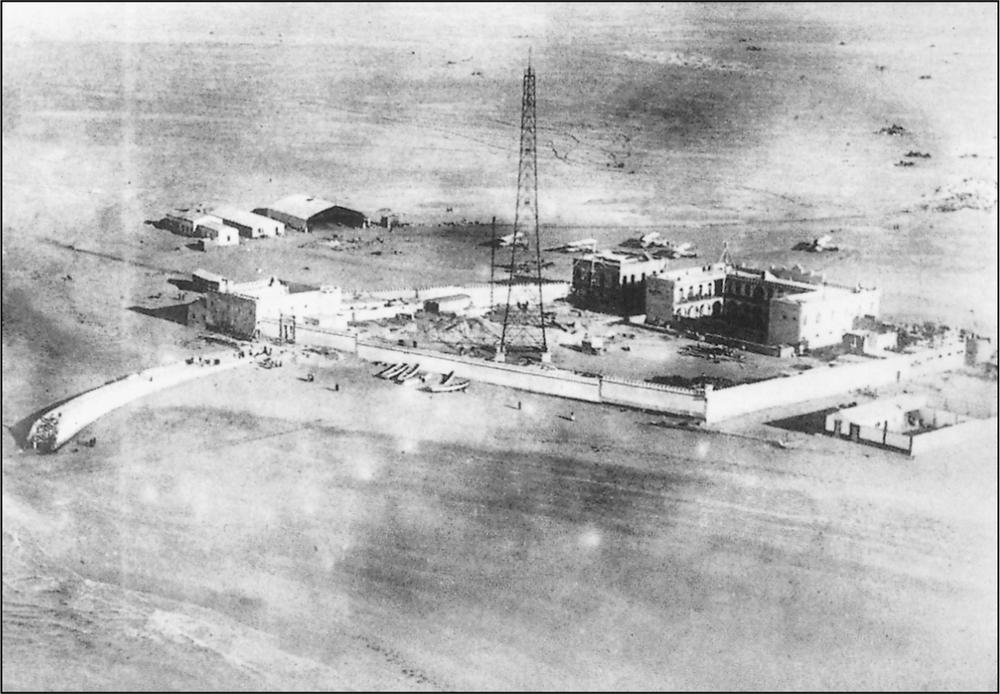

Cap Juby from the air. (

Musée d’Air France

)

The Saharans attacked the fort constantly, the caravans never turned up, profits were non-existent and the Spanish state had to take over.

By 1914, the French had subjugated the interior of the Sahara. In the north, they had occupied Morocco. In Europe, the First World War was being fought. Only in the Spanish Sahara was nothing happening. The commanding officer in Villa Cisneros, Fransisco Bens, had been rotting away there for ten years. Now he put his soldiers onto a ship and sailed north to capture Cap Juby.

The Admiralty found out and ordered the ship to return to Villa Cisneros immediately.

But Bens didn’t give up. On foot, he marched his men north along the coast.

As they approached Cap Juby, they were overtaken by a Spanish cruiser, ordered to board and were once again conveyed ignominiously back to Villa Cisneros.

Not until 1916 was Bens finally able to occupy Cap Juby, this time at the request of the Saharans, who preferred Bens to the aggressive French, and also of the French, who preferred Bens to the aggressive Saharans.

Of course, by then trade had long gone elsewhere and MacKenzie’s island became the Spanish equivalent of Devil’s Island, a prison as loathed by the gaolers as it was feared by the prisoners.

Its little fort was surrounded by two kilometres of barbed wire, says Joseph Ressel, the French writer, there on a visit. At night, nowhere was safe outside the walls. It was difficult to tell the difference between soldiers and convicts: all were unshaven, unwashed and in the same ragged uniforms. The officers sat silently in the mess, playing dice, their faces expressionless.

But in the early 1920s, this godforsaken place gained a sudden importance when the French airline Compagnie Latécoère needed it as a stopover on the first Toulouse-Dakar air route.

And in the mid-1920s, when the Germans and the French were competing for the air routes to South America and German agents supplied the Saharans with arms and ammunition to shoot down French planes – then Cap Juby became a focal point.

In the spring of 1927, a new airport chief was appointed to Cap Juby with the task of rescuing shot-down French pilots and creating better relations with the Saharans. His name was Antoine de Saint-Exupéry.

I loved the airmen in Saint-Exupéry’s books. The pilots of those days were kind of canoeists of the air, with no more than their lower bodies inside the ‘flying machine’, as it was called. Flying was shooting the rapids with the propellor as a paddle.

The primitive, single-engined machines flew below the clouds to see their way. In fog or a sandstorm, they were lost. One in six flights between Cap Juby and Dakar ended in a crash or emergency landing in the desert.

And when the pilot in his thick leather overalls, ‘heavy and cumbersome as a diver’, clambered out of his cockpit – then, if the rescuers did not get to him in time, what awaited him was captivity or death at the hands of hostile nomads. Altogether, 121 pilots were lost.

There was no shortage of exciting adventures in the boys’ books of my childhood. But they had one failing – they had no idea what they were talking about.

If you asked Edward S. Ellis how Deerfoot behaved when he ‘crept invisibly through the thicket’, there would have been a silence. Ellis was not an Indian. He had no idea how it happened. I could see that already from the way he wrote.

Saint-Ex, on the other hand, was a real airman. He knew that the pilot can feel from the vibrations in his own body when fifteen tons of matter has achieved the ‘maturity’ required to take off. He knew what it felt like to separate the plane from the ground – ‘with a movement like picking a flower’ – and let it be borne by the air.

His knowledge was no thin veneer concealing massive

ignorance. He was authentic. When he called the desert sun ‘a pale soap bubble in the mist’, I knew he had seen it. He had been there. It was in his language.

Saint-Ex was the first writer who gave me some sense of what ‘style’ is.

Today, Cap Juby is called Tarfaya. I book in at the Green March hotel. There is no other.

The town is white with blue front doors and flat roofs, a forest of reinforcement rods protruding from the walls – the houses are all prepared for a second floor which has not yet arrived.

The small shops are just holes in the walls, all with an identical assortment of candies, cigarettes, batteries, sewing thread and soft drinks.

I start asking after old people who might have memories of the 1920s. Yes, there should be a few. But while I am waiting for them, a courteous Moroccan policeman comes and asks me to accompany him to the police station.

They already know everything there. The squealing radio with its crackling voices has told them where I have come from, where I have spent the night, which police posts I have passed, all my father’s first names, all my mother’s first names and her maiden name, and also that claim not to know the names of my father’s father or my maternal grandmother.

So I want to talk to old Saharans in Tarfaya, do I? The

chief gendarme is full of goodwill. Tomorrow I am to meet the mayor. He will help me.

I am allowed to see the charming and obliging side of the system of control. Other people get the disappearances and the torture.

The front door of the Green March hotel is kept shut with a thick piece of paper folded twice and jammed in between the door and the doorpost. Whenever anyone fails to do this, the door swings open and slams violently in the wind.

There is a café on the ground floor. For dinner, I am served two eggs apparently fried in waste engine oil. I eat the bread with gratitude.

The café has the town’s only television set. The news begins with the usual good wishes and other courtesies which Hassan, the King, has exchanged with other heads of state. Then comes what Hassan has done during the day, often with flashbacks to what Hassan had done previously on the same day or in the same genre. It ends with a prediction of what Hassan will do tomorrow, illustrated with film of what it looked like when Hassan last did the same thing.

The few seconds left at the end are devoted to other world news.

Then the screen goes blank. Everyone waits patiently. The landlord gets up, climbs onto a chair and puts in a video.

After ten minutes, the tape breaks. Everyone goes on calmly watching. The landlord runs the tape back and starts it again,

the volume higher this time – rather like trying to get through a sandy stretch of road by backing the car, revving the engine and trying it faster.

But it’s no use. The tape gives up at exactly the same place in the action.

No one moves a muscle. Everyone stays seated, full of confidence. The landlord goes to fetch another video. This time we go straight into the middle of a quite different story, the beginning missing. No one reacts. Everyone gratefully goes on watching.

All night the door slams violently in the wind blowing off the sea.

A man has gasped all his life, then draws his first really deep breath. After ‘a life of gasping’, as he calls it, he at last, slowly, with great enjoyment, drinks a large glass of cold air.

A tall yellow building behind the main street dominates the town. The walls are crowned with watchtowers, with open fields of fire in all directions. This is where Colonel Bens resided in 1925. Now it is the Moroccan mayor’s office.

The mayor sits below a preternaturally large photograph of

Hassan and wears an Italian ‘camel-hair ulster’ made of nylon. With him are some old people in real, smelly camel-hair clothes, among them the son of the interpreter who accompanied Saint-Ex on his flights.

He tells me about an emergency landing in the desert. His father kept the ‘bandits’ at a distance with his rifle while Saint-Ex repaired the engine. They took off at dusk with bullets whistling round their ears.

‘That man saved my life,’ said Saint-Ex. Afterwards it was all made into a film so that the whole world could see it.

‘Were you there yourself?’

‘Not me. But Ahmed was.’

The mayor promises to summon Ahmed the next day.

I know which tiles are loose on the steep hotel stairs. Even in the darkness, I can find the footrest of the squatting-toilet. Life in Tarfaya is becoming familiar.

In the mornings, I breakfast on bread and water. Decades old, the bed I am sitting on still has the plastic covering it had been transported in. That probably increases its second-hand value. The bottom sheet is the kind that only goes as far as your knees. There is no top sheet.

Through the little window I can see across the constantly windswept headland to the island with its dark, abandoned prison. Some boys are playing football on the shore, in the wind coming off the sea.

The mayor’s office opens at eight-thirty, but there is no

point going there until half-past ten. I sit in the sun outside the hotel and warm up as I wait. The greengrocer puts his wooden boxes out on the pavement. You buy bread from a blue hatch. A Saharan in a white jibba walks past. They are a rare sight here. Uniformed Moroccans are in the majority.

A small girl with a school bag buys some carrots. A man walks past with a large bunch of fragrant mint. His feet are cracked. Fish are being weighed on the corner – some a type of perch, vertically striped or long and silvery with horizontal stripes, glittering in the morning light.

At about half-past ten, I meet Ahmed, aged eighty-five.

‘Saint-Ex was different. He tried to learn our language. None of the Spaniards did that. He studied with a teacher of the Koran called Sidi l’Hussein Oueld n’Ouesa. The Spaniards just sat in their fort. They didn’t fly. But Saint-Ex was a travelling man, so he had to be able to speak languages. He was a man who knew how to negotiate and often did so over men held for ransom.’