Desert Divers (5 page)

Authors: Sven Lindqvist

He now breaks free and staggers off into town.

The ground is strewn with dark stones. Not a human being in sight. Everything is in ruins.

He buries a bottle with a message in it to show that he and his brother have ‘discovered’ Smara – a final game of pretence before he crawls back into the pannier and begins the return journey.

Vieuchange in front of Smara.

‘I got there,’ he writes in his journal. ‘But like a pearl-diver, I must immediately return.’

He spent three hours in Smara. The return journey took a month. He died in Agadir on November 30, 1930.

Actual cause of death: dysentery.

Real cause of death: romanticism.

‘The more light the desert receives, the darker it seems to become,’ writes Eugène Fromentin.

Desert romanticism exists in that kind of paradox. Otherwise one must ask what a romantic is doing in the desert at all. The desert has no leafy groves, fragrant meadows, deep-soughing forests, or anything else which usually evokes in the romantic the right emotions. Desert romanticism already appears incomprehensible at a distance. Up close, it becomes absurd. What is romantic about an endless gravel pit?

Eugène Fromentin can tell you what. He wrote the classic desert book

A Summer in the Sahara

(1857). He is the first of a long line of writers and artists to experience the desert with an aesthetic eye.

Fromentin loves the desert because it has no appeal, because it is never lovely. He loves the expansiveness of its lines, the emptiness of its space, the barrenness of its ground. At last a sea which does not swell, but consists of a firm, immovable body. At last a silence which is never broken in a desolate country where no one comes and no one goes.

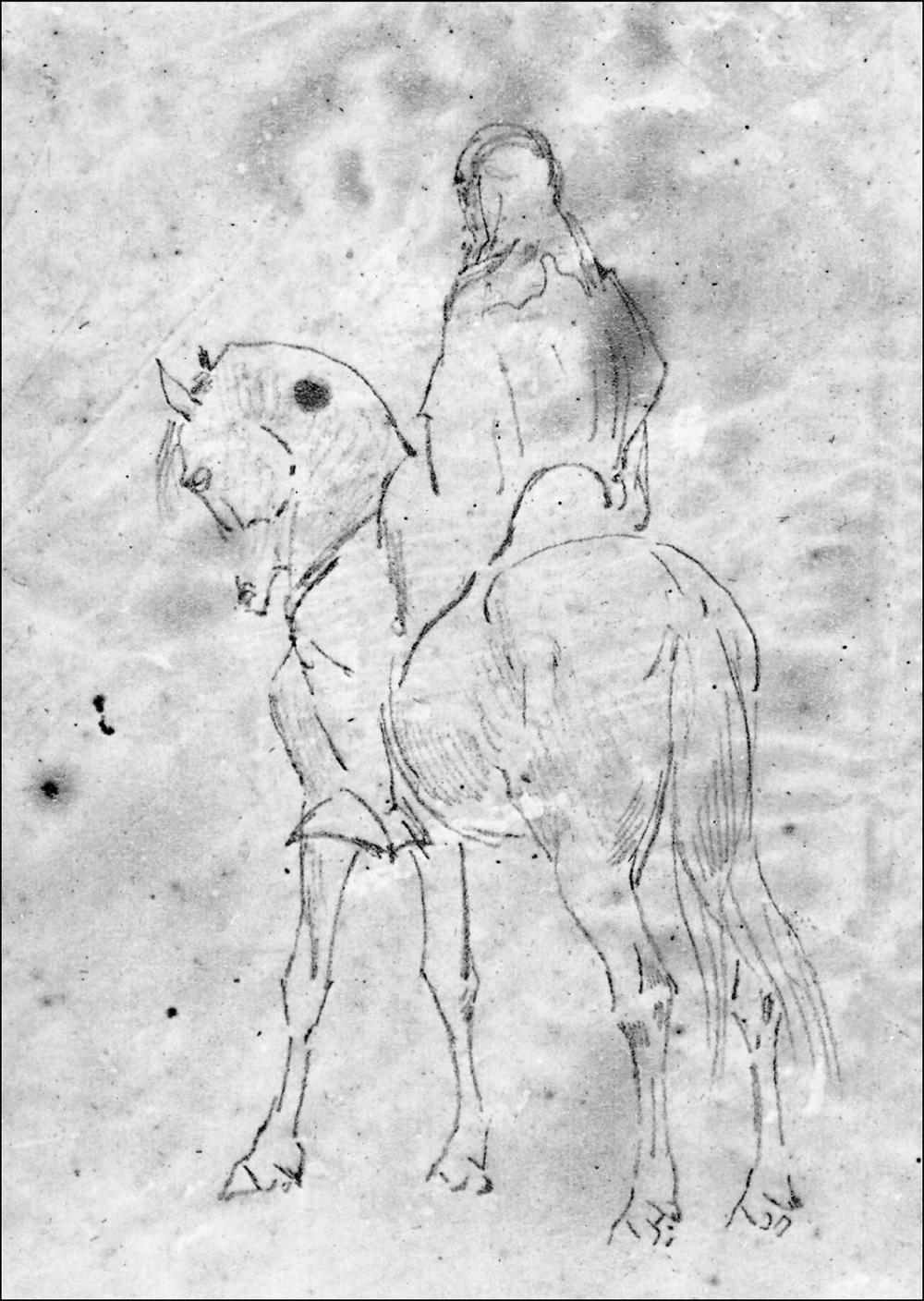

Eugène Fromentin,

Arab Horseman

. (

Musée des Beaux-Arts de La Rochelle

)

Eugène Fromentin,

Interior of Arab tailor’s workshop

. (

Private collection, descendants of Eugène Fromentin

)

Strangely, that same silence seems so threatening in the town, lying there dark and mute under the sun.

The people appear to have lost their power of speech. They surround him with an immeasurable gravity, as mute and scorched as the landscape they inhabit.

Why this silence? Is it the sun? The heat makes the air vibrate with a faint but entirely audible note. The ground itself seems to gasp. Day and night change places. The midday sun annihilates and kills, the midnight darkness revives and gives life.

Fromentin sets off on nightly wanderings in town. But the inhabitants are just as hostile in the dark hours. They do not greet him. They pretend not to see him.

So that is what the Arab is – a man unwilling to show you his house, unwilling to say his name or say what he is doing or tell you where he is going. ‘All curiosity is unwelcome to him.’

It must be the sun which has made the Arab like that. Fromentin feels himself being influenced. The sun persecutes him right into the night. ‘I dream light,’ he complains.

He stands all day out in the desert, painting, bathing in the sun. In the evening he is feverish from all the light his body has absorbed. Even when he closes his eyes he sees sparks, flames and circles of light in the darkness. ‘I have no night, so to speak.’

People of the desert have lived under that sun since they were children. The terrible desert sun has marked them with its lack of emotion ‘which has fallen from the sky onto objects and from objects has transferred to their faces’.

Hence the silence.

I’ve come from Algiers. I have rented a small Renault 4, buckled at all four corners and with the driver’s seat sagging so much that it hits the floor. They did not want to let any other car go out into the desert. ‘A single sandstorm takes off the paintwork in a few hours,’ they said. So I put a couple of books and a rolled-up towel behind me and steered the little wreck out into the traffic of Algiers.

Algiers is a climbing town, all the streets on their way upwards or downwards, the traffic heavy and eternally at a standstill, until it suddenly hurtles forward with the roar of a

tiger. I have seldom come across such a constant need to demonstrate the potency of your automobile and your driver’s daring as I have here.

In a R4, there is nothing to do but calmly allow yourself to be passed on both sides, often so closely that your crumpled shirt gets a pressing into the bargain. So I cope with the latest passer’s stinking exhaust fumes, perhaps muttering something about the fact that he is driving on camel shit to honour his mother.

Arabic oaths are often descriptions of the sexual behaviour with camels of the mother of the person concerned. Anyone who manages to combine the anal insult with the sexual gains extra points.

The road slices up the mountainside in sharp turns like a fretsaw. The R4 has no strength to fall back on – the trick is to accelerate between gears, as in the old days of double-declutching, and keep the engine running. Then the tough little car manages the Atlas mountains, and when I finally reach level ground, we get up to 60 mph, even 70 in successful moments.

It rumbles and it sways, but I can’t help liking the R4 for the wind whistling through the coachwork and the sewing-machine buzz of the engine as it patiently carries me towards Laghouat.

Algeria is in the middle class of the world’s countries. That is clear from the road, which is not dominated by shepherds and flocks of sheep but by heavy transporters – steel girders, pipes, cement. Roadworks occupy more machines than people – though the unemployed, currently 17%, would fight to be allowed to shovel macadam.

In the villages I try to buy some food for lunch, but there is only bread. There is always bread, subsidized by billions, very cheap to buy and sold in great quantities. Fresh morning

bread has already been thrown away at midday to be replaced by even fresher afternoon bread. Even far out in the countryside, these bread habits have been adopted from the French and are considered sacred – Algeria literally throws away her oil income in the form of dry bread. A country which on liberation in 1962 was a great exporter of food now produces only 35% of what its people eat or throw away.

‘

C’est

la crise, c’est normale

,’ they say in the shops as an explanation for there being no tea, no coffee, no sugar, no eggs – well, more or less nothing but detergents and powdered milk.

But there are schools. Everywhere I see children on their way to or from school. The first shift begins at dawn, the last is on its way home as the sun sets. Caring for the children and giving them an education despite 3.2% annual growth in population is the heroic feat of the schoolteachers – minor intellectuals who for twenty-five years have accepted these triple shifts, these remote posts in the countryside and these low salaries, to cope with the great task of teaching the people to read. But who feel themselves more and more deceived and abandoned as the years go by and others enrich themselves.

What did their sacrifices give them? When will things get better? In twenty years, when the oil runs out?

I stay with a teacher’s family in Laghouat. My friend Ali, whom I got to know in the rue Valetin gym in Algiers. His brother Ahmed is leader of the big band ‘Desert Brothers’. Like most young Algerians, they are enraged by the corrupt misrule.

‘Before independence, we had five parties in the country. Now we’re not considered mature enough to have more than one. What people lack is not maturity, but power!’

All evening we sit round the big couscous dish until the

meal is concluded with milk and dates. Then we all sleep together in the best room.

The moisture from our breathing glistens on the cold walls. Outside, the stars sparkle as brightly as only desert and darkness can make them. The silence is boundless, and the occasional distant barking of a dog makes it audible.

Early in the morning, I go up onto the roof. It is a beautiful day. White clouds have accumulated on the horizon like a further layer of sediment on dark mountains.

This is where Fromentin stood 130 years ago. The landscape we see is the same. The same sun, the same desert.

But not the same people. His Arabs were closed, menacing, hostile. Those I have met are open, lively, hospitable people.

Under the same sun.

Fromentin was wrong to think the merciless sun had marked the people of the desert for ever. Perhaps he actually knew that himself. In the 1980s,

A Summer in the Sahara

was published in new academic editions which also account for variations in the text. In them you find other explanations for the silence in Laghouat.

In the spring of 1830, Paris was already seething with the rebellion which was to find its outlet in the July revolution. De Polignac’s militantly reactionary government was about to fall. As a final way of diverting dissatisfaction, it was decided to attack Algiers, on the pretext of an alleged insult to the French Consul.

In their proclamations to the people, the French said they had come to liberate the Arabs from Turkish oppression and make them ‘lords in their own mansions’. But the supposed liberators committed the most hideous atrocities and retained power wherever they could seize it.

France under the July monarchy decided to keep just Algiers and its immediate surroundings; but the military was not to be deterred. Villages were burnt down in their hundreds, and thousands of refugees died of starvation. By the time the February revolution introduced the second empire, Algerian resistance had been broken all along the coast.

The mountains and the deserts remained. No political decision could stop the conquest that continued with military logic. On December 3, 1852, it was Laghouat’s turn. The French seized the town after a two-day siege. Forty-five years later, the commanding officer described in his memoirs what happened next:

The town had to endure all the horrors of war, experience all the atrocities that can be committed by soldiers when they are left for a moment to themselves, still feverish from the dreadful fighting, raging over the dangers they have undergone and the losses they have

suffered, excited by their hard-won victory. Terrible scenes were enacted.

Fromentin arrived in the early summer of 1853, scarcely six months after the massacre. ‘I feel neither joy nor happiness here,’ he writes. ‘Difficult to explain why …’

Every morning, I go up onto the roof and sit there for a while, looking out over the brown slopes surrounding the town. They are covered with fresh green bushes and trees, although everywhere the actual ground is dry and infertile. The moisture has retreated from the sun and the winds, further down into the ground. That is where the roots seek it out.

Yesterday I drove through flowering nerium, a bush named after the Greek word for water,

nero

. It has a brilliant ability to find water at great depths and human water-diviners have always followed its roots.

The contrast between surface and depths, between what the eye sees up here and the real circumstances down there, are the fundamental experience of the desert.

From my viewpoint on the roof, I can follow the route of the victorious French into town. Fromentin did the same when the stench of corpses was still in the air. A French lieutenant who was present told him:

We literally waded in blood, and for two days it was impossible to get anywhere for the heaps of corpses.

Not only hundreds of men, shot or with bayonet wounds all over them, but also – why not say it as it is? – the bodies of huge numbers of women, children, horses, donkeys, camels, yes, even dogs … A terrible book could be written about the episodes I heard tell of the following morning alone, of what had been enacted during the two or three hours the reprisals lasted …

Fromentin didn’t write that book. He deleted the lieutenant’s story from his manuscript and contented himself with a summary: ‘They waded in blood; there were corpses by the hundred.’

In Fromentin’s writing, too, there is a contrast between surface and depth, between what the eye sees up there and the actual circumstances further down. In one place in the manuscript he asks: ‘A third of the population killed – with what right, because of what crime or what threat and with what doubtful results?’

But he at once stops himself: ‘I have no right either to describe or to judge a victory of this kind.’

Nor did he try. He deleted the passage. He blamed the silence in Laghouat on the climate. It became romanticism.

The survivors of the massacre had fled south. Some returned and were then directed to inferior neighbourhoods, all their possessions confiscated, and the entire booty of mats, weapons,

jewellery and clothes removed. ‘All the houses from the poorest to the wealthiest are empty,’ Fromentin writes.