Devil's Knot: The True Story of the West Memphis Three

Read Devil's Knot: The True Story of the West Memphis Three Online

Authors: Mara Leveritt

The Boys on the Tracks

1230 Avenue of the Americas

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

Copyright © 2002 by Mara Leveritt

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Atria Books, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

ISBN: 0-7434-1761-5

ATRIA

BOOKS

is a trademark of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Visit us on the World Wide Web:

http://www.SimonSays.com

To LSB,

with love and gratitude

I thank my beloved family; my many generous friends; the filmmakers, musicians, and other artists who have recognized this story’s importance; the reporters whose accounts have contributed to this book; the public officials who provided information and access to records; the lawyers who explained aspects of the case; and everyone who granted me interviews. I thank, in particular, Sandra Dijkstra, Wendy Walker, Tracy Behar, Judith Curr, Ron Lax, Dan Stidham, Burk Sauls, Grove Pashley, Kathy Bakken, Stan Mitchell—and, of course, the inmates whose story this is.

Many of the figures in this book were juveniles when the key events took place. Others were on the cusp of adulthood. One or two had recently reached their majority. It is customary in reporting events involving children to refer to them by their first names. I have tried, in general, to do this. The ages of two of the accused, as well as many of the witnesses, were factors in the events related here. I felt that it would distort the story to refer to the children in it as though they were adults, though most were treated as adults by the legal system.

Three teenagers figure at the center of this book. Although one of them had recently observed his eighteenth birthday at the time this book begins, I opted to refer to all three consistently by their first names.

Because of the attention this case has received—and the further scrutiny I believe it deserves—I have written it on two levels. The text tells the story. The endnotes deepen it.

Occult.

1. Hidden (from sight); concealed (by something interposed); not exposed to view. 2. Not disclosed or divulged, privy, secret; kept secret; communicated only to the initiated. 3. Not apprehended, or not apprehensible, by the mind; beyond the range of understanding or of ordinary knowledge; recondite, mysterious. 4. Of the nature of or pertaining to those ancient and medieval reputed sciences (or their modern representatives) held to involve the knowledge or use of agencies of a secret and mysterious nature (as magic, alchemy, astrology, theosophy, and the like); also treating of or versed in these; magical, mystical.

Oxford English Dictionary

W

ERE THE

W

EST

M

EMPHIS

trials witch trials?

Had a jury sentenced someone to death based on nothing more than children’s accusations, confessions made under pressure, and prosecutors’ arguments linking the defendants to Satan?

Were the 1994 trials in Arkansas like those in Salem three centuries ago?

These were the questions that gave rise to this book. These, and a couple more:

If talk of demons had diverted reason,

how

had things gone so awry—in the United States of America, at the end of the twentieth century—before not just one jury but two, in trials where lives were at stake? And if something so terrible had happened,

why

?

Modern readers might think it impossible that prosecutors in a murder case, facing a dearth of factual evidence, would build their argument for execution on claims that the accused had links to “the occult.” Educated readers might recoil from the idea that prosecutors would cite a defendant’s tastes in literature, music, and clothing to support such an archaic theory. Even fans of lurid fiction might find it a stretch to believe that a prosecutor in this day and age would point to a defendant and say, “There’s not a soul in there.”

Yet in the spring of 1994, that is what

seemed

to have happened. A teenager was sentenced to death. His two younger codefendants were dispatched to prison for life.

Impossible.

And yet the police insisted that their case was strong. The judge who presided at the trials said that they had been fair. And in two separate opinions, the justices on the Arkansas Supreme Court agreed. Unanimously.

Outside the state, however, news of the unusual trials began to attract attention. A documentary released in 1996 raised widespread concern. A Web site was dedicated to the case, and its founders unfurled the phrase “Free the West Memphis Three.”

Arkansas officials dug in. As criticism mounted, police and state officials insisted that the film had been misleading. They pointed out that twenty-four jurors had sat through the trials, had heard and seen all the evidence, and had found the teenagers guilty. They said that anyone who bothered to examine what “really” had happened in the case, rather than form opinions based on movies and a Web site, would conclude, as had the jurors, that justice had been served.

As an Arkansas reporter focusing on crime and the courts, I began to see this as a historic case. The dispute needed to be resolved. Either the out-of-state critics were wrong, in which case the “Free the West Memphis Three” crowd could all get on with their lives, or something similar to what happened at Salem had indeed occurred again—during my lifetime and in my own state.

I decided to take my state’s officials up on their challenge. I would look at what “really” had happened. I would interview participants, read thousands of pages of transcripts, touch every piece of evidence in storage, and report faithfully on what I found, regardless of whom it supported. And if what I found in West Memphis resembled what had happened in Salem, I was prepared to look further. We assume that secularism, as well as advances in science and law, distances us from colonial America. If it appeared, as critics of the West Memphis case charged, that presumably rational processes had given way to satanic allusions, it was fair to ask both

how

and

why

such a thing had happened.

The Investigation

Chapter One

The Murders

A

T

7:41

P.M. ON

M

AY

5, 1993, a full moon rose behind the Memphis skyline. Its light glinted across the Mississippi River and fell onto the midsized Arkansas town aspiringly named West Memphis. Sometime between the rising of that moon and its setting the next morning, something diabolical would happen in West Memphis. Three eight-year-old boys would vanish, plucked off the streets of their neighborhood by an unseen, murderous hand. Under the glare of the next day’s sun, police would discover three young bodies. They would be pulled—naked, pale, bound, and beaten—from a watery ditch in a patch of woods alongside two of America’s busiest highways. But the investigation would unfold in shadow. Why had one of the boys been castrated? How to account for the absence of blood? Why did the banks of the stream look swept clean? The police would stumble for weeks without clues—until the moon itself became one.

John Mark Byers, an unemployed jeweler, was the first parent to report a child missing.

1

At 8

P.M

., with the full moon on the rise, Byers telephoned the West Memphis police. Ten minutes later, a patrol officer responded.

2

She drove her cruiser down East Barton Street, in a working-class neighborhood. At the corner where Barton intersected Fourteenth Street, the officer stopped in front of the Byerses’ three bedroom house. Byers, an imposing man, six feet five inches tall, weighing more than two hundred pounds, with long hair tied back in a ponytail, met her at the door. Behind him stood his wife, Melissa, five feet six, somewhat heavyset, with long hair and hollow eyes. Mark Byers did most of the talking. The officer listened and took notes. “The last time the victim was seen, he was cleaning the yard at 5:30

P.M

.” That would have been an hour and twenty minutes before sunset. The Byerses described Christopher as four feet four inches tall, weighing fifty pounds, with hair and eyes that were both light brown. He was eight years old.

The officer left the Byerses’ house, and within minutes was dispatched to another call, at a chicken restaurant about a mile away. She pulled up at the Bojangles drive-through at 8:42

P.M

. Through the window, the manager reported that a bleeding black man had entered the restaurant about a half hour before and gone into the women’s rest room.

3

The manager told the officer that the man, who had blood on his face and who had seemed “mentally disoriented,” had wandered away from the premises just a few minutes before she arrived. When employees entered the rest room after he left, they found blood smeared on the walls. The officer took the report but investigated the incident no further. At 9:01, without ever having entered the restaurant, she drove away to a criminal mischief complaint about someone throwing eggs at a house.

At 9:24

P.M

., the same officer responded to another call, again from Barton Street—this one from the house directly across from the Byerses’. Here a woman, Dana Moore, reported that her eight-year-old son, Michael, was also missing.

4

Taking out her pad again, the officer wrote, “Complainant stated she observed the victim (her son) riding bicycles with his friends Stevie Branch and Christopher Byers. When she lost sight of the boys, she sent her daughter to find them. The boys could not be found.” Moore said the boys had been riding on North Fourteenth Street, going toward Goodwin. That had been almost three and a half hours earlier, at about 6

P.M

. By now, it had been dark for more than two hours. “Michael is described as four feet tall, sixty pounds, with brown hair and blue eyes,” the officer wrote. “He was last seen wearing blue pants, blue Boy Scouts of America shirt, orange and blue Boy Scout hat and tennis shoes.”

By now a second officer had been dispatched to a catfish restaurant several blocks away. There another mother, Pamela Hobbs, was reporting that her eight-year-old son, Stevie Edward Branch, was missing as well. Hobbs lived at Sixteenth Street and McAuley Drive, a few blocks away from the Byerses and the Moores. She reported that her son, Stevie, had left home after school and that no one had seen him since. The officer who took Hobbs’s report did not note who was supposed to have been watching Stevie while his mother was at work, or who had notified Hobbs that her son was missing. Stevie was described as four feet two inches tall, sixty pounds, with blond hair and blue eyes. The police report noted, “He was last seen wearing blue jeans and white T-shirt. He was riding a twenty-inch Renegade bicycle.”

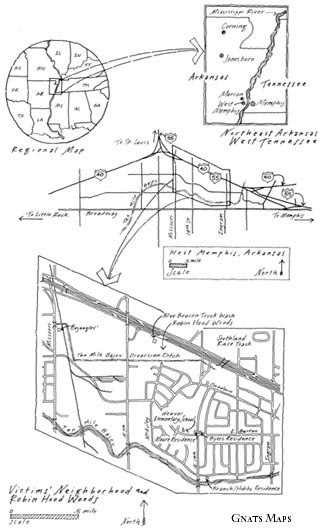

Word of the disappearances spread quickly through the subdivision. As groups of parents began searching, other residents reported that they had seen some boys—three, or maybe four—riding bikes near the dead end of McAuley Drive shortly before sunset. McAuley was a major street in the neighborhood. The house on McAuley where Stevie Branch lived was a few blocks south of the corner on Barton where the other two missing boys lived across the street from each other. From Stevie’s house, McAuley wound west for a few blocks, ending at the edge of a four-acre patch of woods, a short distance northwest of the other boys’ homes. The woods separated the subdivision from two interstate highways and their service roads on the north. The small sylvan space provided the neighborhood with a welcome buffer from the traffic on their northern edge. For a few diesel-fumed miles, east-west Interstate 40, spanning the United States between North Carolina and California, converges in West Memphis, Arkansas, with north-south I-55, connecting New Orleans to Chicago. For truckers and other travelers, the stretch is a major midcontinental rest stop; where the highways hum through West Memphis, the city has formed a corridor of fueling stations, motels, and restaurants. It was easy for anyone passing through not to notice the small patch of woods bordering that short section of highway. What was more noticeable was the big blue-and-yellow sign for the Blue Beacon Truck Wash that stood several yards from the edge of the woods, alongside the service road.

Just as truckers knew the Blue Beacon, kids in the neighborhood to the south were familiar with the woods. The small plot of trees represented park, playground, and wilderness for children and teenagers living in the subdivision’s modest three-bedroom houses and in the still more modest apartment building nearby.

5

That the woods existed at all was an acknowledgment, not of the need for parks or of places for children to play, but of the need for flood control. Years earlier the city had dredged a channel, unromantically known as the Ten Mile Bayou Diversion Ditch, to dispose of rainwater that ordinarily would have flowed into the Mississippi River but that was prevented from draining by the great levees that held back the river. While the levees kept the Mississippi at bay, rainwater trapped on the city side of the levee had posed a different flood problem for years. The Ten Mile Bayou Diversion Ditch was dredged to direct rainwater around the city to a point far to the south, where a break in the Mississippi levee finally allowed it to drain. Part of that ditch ran through this stand of trees. In places, the ditch was forty feet wide and could fill three or four feet deep. Tributaries, such as the one that drained the land directly behind the Blue Beacon, formed deep gullies in the alluvial soil. Together, the combination of trees, ravines, water, and vines made the area a hilly wonderland for kids with few unpaved places to play.

They called the woods Robin Hood. Adults tended to make the name sound more proper, calling it Robin Hood Hills, but it was always just Robin Hood for the kids. Under its green canopy they etched out bike trails, built dirt ramps, established forts, and tied up ropes for swinging over the man-made “river.” They fished, scouted, camped, hunted, had wars, and let their imaginations run. But at night, when the woods turned dark, most kids stayed away. The place didn’t seem so friendly then, and the things that parents could imagine translated into stern commands.

Besides the risks from water and Robin Hood’s closeness to the highways, parents worried about transients who might be lurking there. Many parents warned their children to stay out of the woods entirely. But the ban was impossible to enforce. Robin Hood was too alluring. And so it was inevitable, on that Wednesday night in May, as word flew from house to house that three eight-year-olds were missing, that parents would rush to the dead end of McAuley, where a path led into the woods. It was about a half mile from the homes of Christopher Byers and Michael Moore and only a few blocks farther from that of Stevie Branch.

The delta was already beginning to warm up for the summer. At 9

P.M

., even on May 5, the temperature was seventy-three degrees. An inch of rain a few days before had already brought out the mosquitoes.

6

The insects were a nuisance everywhere, but they were especially thick in places that were moist and overgrown—shady places like the woods. The officer who’d taken the missing-person reports on Christopher Byers and Michael Moore later reported that she’d ventured into the woods near the Mayfair Apartments to help look for the boys, but the mosquitoes had driven her out. The officer who’d taken the report on Stevie Branch also said later that he’d entered the woods and searched with a flashlight for half an hour. But those two efforts were the only police action that night. No organized search by police would begin until the morning.

7

As officers assembled at the West Memphis Police Department for their usual briefing on Thursday morning, May 6, 1993, Chief Inspector Gary W. Gitchell, head of the department’s detective division, announced that three boys were missing and that he would be directing the search. A search-and-rescue team from the Crittenden County Sheriff’s Office would be assisting. When a few hours had passed without sign of the boys, the police department across the river in Memphis, Tennessee, dispatched a helicopter to assist. By midmorning, dozens of men and women had also joined police in the search. Detectives and ordinary citizens checked yards, parking lots, and various neighborhood buildings, including some still damaged from a tornado that had struck the town the year before. Others fanned out across the two miles of fertile, low-lying farmland that separates the east edge of West Memphis from the levee and the Mississippi River. The most intensive search, however, remained focused on the woods. For hours, groups of as many as fifty law enforcement officers and volunteers combed the rough four acres that lined the diversion ditch. At one point the searchers gathered on the north edge of the woods, near the interstates, and marched shoulder-to-shoulder across the woods until they emerged on the other side, near the houses to the south. But even that effort turned up nothing. Members of the county search-and-rescue team slipped a johnboat into the bayou and poled it down the stream. But still, nothing. By noon, most of the searchers, their alarm increasing, had abandoned the woods to search elsewhere.

But one searcher stayed. Steve Jones, a Crittenden County juvenile officer, was tromping through the now empty section of the woods nearest to the Blue Beacon Truck Wash when he looked down into a steep-sided gully, a tributary to the primary ditch, and spotted something on the water. Jones radioed what he had found.

8

Entering the woods from the subdivision side, Sergeant Mike Allen of the West Memphis Police Department rushed across a wide drainpipe that spanned a part of the ditch, and clambered to where Jones was waiting. Jones led Allen to a spot about sixty yards south of the interstates. Standing on the edge of a high-sided bank, Jones pointed down at the water. Floating on the surface was a boy’s laceless black tennis shoe.

The time was approximately 1:30

P.M

. The area had been searched for hours. Yet here, alarmingly, was a child’s shoe. Police converged on the spot. Sergeant Allen, wearing dress shoes, slacks, a white shirt and tie, was the first to enter the water.

9

It was murky, with shoe-grabbing mud on the bottom. Allen raised a foot. Bubbles gathered around it and floated to the surface. The muck beneath his shoe made a sucking, reluctant sound. Then a pale form began to rise in the water. Slowly, before the horrified officers’ eyes, a child’s naked body, arched grotesquely backward, rose to the surface. It was about 1:45

P.M

.

10

Word of the discovery spread like fire through West Memphis. Searchers swarmed back to the woods, but now only Gitchell’s detectives were being let in. By 2:15

P.M

., yellow crime tape was up. Police cars were stationed at the McAuley Drive entrance to the woods and at the entrance south of the Blue Beacon. For the detectives, in a dense and seldom visited part of the woods kids called Old Robin Hood, the job ahead was as odious as obvious. If one body had been submerged in the stream, the others might be as well. Detective Bryn Ridge volunteered for the unnerving job. Leaving the first body where it floated, the dark-haired, heavyset officer walked several feet downstream and waded into the water. Lowering himself to his knees, he spread his hands on the silty bottom. Then slowly, on all fours, he began to crawl up the narrow stream, searching the mud with his hands, expecting—and dreading—that at any moment he would touch another dead child. He encountered instead a stick stuck unnaturally into the mud. He could feel something wrapped around it. Dislodging the stick and pulling it up, he found a child’s white shirt.

Carefully, Ridge stood up and returned to the floating body. It didn’t seem right to him to leave it there. He lifted the body to the bank. The officers knew from photographs they’d been shown of the missing boys that this was the body of Michael Moore. And they could see that between the time the boy was last seen and now, he had endured tremendous violence. Michael’s hands and feet were behind him, bound in what some would describe as a backward, hog-tied fashion. But it wasn’t that, exactly. The limbs weren’t tied together. Rather, the left ankle was tied to the left wrist; the right ankle and right wrist were tied. The boy had been tied with shoelaces. The bindings left the body in a dramatically vulnerable pose. The boy’s nakedness, the unnatural arch of the back, and the vulnerability of his undeveloped sexual organs, both to the front and to the back, suggested something sexual about the crime. The severity of the wounds to his head suggested a component of rage.