Dickinson's Misery (26 page)

Read Dickinson's Misery Online

Authors: Virginia; Jackson

In Crain's lovely description of the child'sâand the culture'sâdisciplinary incorporation of the

ABC

s, she evokes a lyric moment of alphabetic mimesis, a moment in which printed letters themselves furnish (in all sorts of lifelike postures) the intersubjective confirmation of the self. Further, Dickinson's pastiche of fragments of ballad and fragments of hotpressed paper mimes rather exactly Mill's lyric media. Dickinson's valentines to Howland and Cowper Dickinson use the materials of her culture's invitation to lyric imprinting to keep that genre of intersubjective confirmation at a distance. Instead, they invite the reader to share their resistance to popular song's romance as well as the

ABC

's disciplinary tutelage (thus the calls to arms in the Howland valentine), literally constructing the fantasy of a conspiratorial counterliteracy mediated by sheets of paper converted to purposes that were not intended by the man who made them.

Figure 19. Emily Dickinson to William Cowper Dickinson, around 1852. Courtesy Yale University Library, Manuscripts and Archives.

Martha Nell Smith has suggested that we regard Dickinson's cut-outs, occasional sketches, and collages as “cartoons,” or send-ups of and challenges to “the literary, political, and family institutions that have helped to reproduce the cartoon-like image of a woman poet commodified.”

36

Yet that restrospective view of the poetess in white (or, more recently, in leather) has more to do with the cultural caricature of Emily Dickinson after her publication as a lyric poet in the twentieth century than it does with Dickinson's use of the nineteenth-century materials of literate circulationâor of the transmission of various literacies.

37

Smith is surely right that recent exposure (for which Smith herself is largely responsible) of what at least some of Dickinson's poems “really looked like” will change popular views of the sort of poetry she wrote, or the kind of poet people think that Dickinson was. But most readers will still think that such youthful pieces of ephemera have little to do with Dickinson's mature lyrics. That may be why the first edition of Dickinson's

Poems

in which the valentine to Howland appeared was Johnson's 1955 scholarly edition, and the valentine to Cowper Dickinson has never been published as a poem at all. As Austin Warren complained at the time of Johnson's edition, “many of [Dickinson's] poems are exercises, or autobiographical notes, or letters in verse, or occasional versesâ¦. But the business of the scholar is to publish all the âliterary remains.'”

38

We could, like Warren, dismiss such contingent phenomena as of interest only to scholars in order to be

readers

of Dickinson's lyrics, but to do so would mean ignoring the fact that the distinction between poems (in more than one sense) and letters (in more than one sense) was not an issue that simply arose for Dickinson's editors and critics after her “literary remains” were recovered; it was a distinction present to Dickinson and her readers throughout her writing life, from the early gushing letters and occasional verse to the later gushing letters and occasional verse. It was also an issue often agonizingly rather than comically at stake in the verse that has come to be considered not cartoonish or occasional but, above all, lyrical.

OUâTHEREâ

I

âHERE

”

In fascicle 33, three sides of two folded sheets of laid, cream, faintly ruled stationery are taken up by the lines that are now Poem 706 in Franklin's edition (

figs. 20a

,

20b

). These lines were among the poems published in the first edition of 1890 (under the title “In Vain”), and they have often been read since as testimony of Dickinson's isolation. Even more often, their invocation of a pathos of literal seclusion has been identified with a pathos of figurative seclusionâthat is, with Dickinson's lyric self-address. As far as we know, the lines were not also sent as a letter, and the only manuscript copy of them that has survived is included in the fascicle.

39

If, however, “I cannot live with Youâ” tells us, as Cynthia Griffin Wolff has suggested, “more about Emily Dickinson herself than any other single work,” it is remarkable that it should say “I” by saying “you” so often (more often than does any other published Dickinson lyric).

40

As Sharon Cameron has written, “we must scrutinize the poem carefully to see how renunciation can be so resonant with the presence of what has been given up” (LT 78):

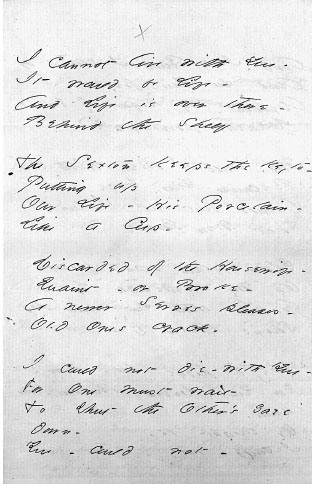

Figure 20a. From fascicle 33 (H 41). By permission of the Houghton Library, Harvard University.

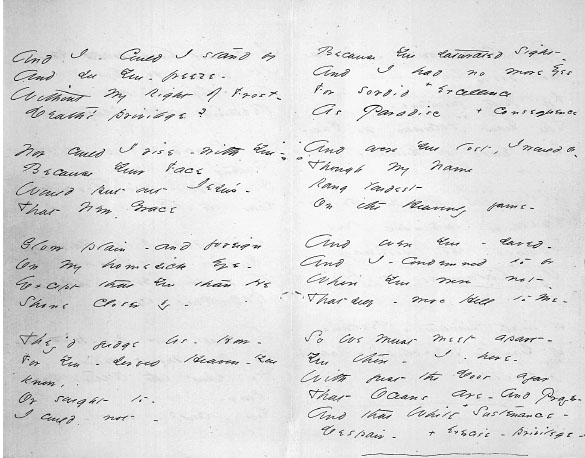

Figure 20b. From fascicle 33 (H 41). By permission of the Houghton Library, Harvard University.

I cannot live with Youâ

It would be Lifeâ

And Life is over thereâ

Behind the Shelf

The Sexton keeps the Key toâ

Putting up

Our LifeâHis Porcelainâ

Like a Cupâ

Discarded of the Housewifeâ

Quaintâor Brokeâ

A newer Sevres pleasesâ

Old Ones crackâ

I could not dieâwith Youâ

For one must wait

To shut the Other's Gaze downâ

Youâcould notâ

And IâCould I stand by

And see Youâfreezeâ

Without my Right of Frostâ

Death's Privilege?

Nor could I riseâwith Youâ

Because Your Face

Would put out Jesus'â

That New Grace

Glow plainâand foreign

On my homesick eyeâ

Except that You than He

Shone closer byâ

They'd judge UsâHowâ

For Youâserved HeavenâYou know,

Or sought toâ

I could notâ

Because You saturated sightâ

And I had no more eyes

For sordid excellence

As Paradise

And were you lost, I would beâ

Though my name

Rang loudest

On the Heavenly fameâ

And were Youâsavedâ

And Iâcondemned to be

Where You were not

That selfâwere Hell to meâ

So we must meet apartâ

You thereâIâhereâ

With just the Door ajar

That Oceans areâand Prayerâ

And that White

x

Sustenanceâ

Despairâ

x

ExerciseâPrivilegeâ

These lines are indeed resonant with the presence of what is absent, though perhaps this is because it is not the object of addressâthe phenomenal “You” her or himselfâthat is here renounced but instead a figure for “you” (the first of what will be a series of such figures) that is considered and found wanting. What is strategically renounced, in other words, is not the presence of the other but the way in which figurative language works to replace that other with an illusion of presence that would mean the other's death. It is this illusion that the lines try hard not to forget. The results of forgetting are abruptly enacted in the oddly extended initial comparison of “Our Life” to “a Cup // Discarded of the Housewifeâ” and locked away by the “Sexton.” When what “would be Life”âthat is, the full presence that would cancel language, that would make writing unnecessaryâleaves “Our” hands it becomes reified into figure. In Dickinson's stunningly contracted line, the passage from redundant presence to figurative absence is a matter of shifting pronouns: “Our LifeâHis Porcelainâ.” Like the “

cracker man

” and “the man who makes sheets of paper” in Dickinson's letter to Susan, the Sexton who “keeps the Key” seems at first an agent of invasion and constraint, the representative of the (notably masculine) public world imposing his law upon “Our Life.” But what a Sexton does, we recall, is, according to Dickinson's dictionary, “to take care of the vessels, vestments, &c., belonging to the church.”

41

For the Sexton, sacramental symbols are

things

(“Our LifeâHis Porcelainâ”) and so can be handled “Like a Cup,” valued or devalued (“Discarded”) according to the hands they fall into. The Sexton does not stand for what separates “I” from “You,” for a public law to which “Our [private] Life” is opposed; rather, what the Sexton represents is the transformation of “Our Life” into figure. Once that figure is introduced, the simile takes over, intensifying

the sense of referential instability signaled by the change in pronouns and by the apparently arbitrary little narrative of the Housewife. The Sexton and the Housewife are thus the antitypes to the “drivers and conductors” of Dickinson's letter: they take the figure of the “Cup” literally and, forgetting that it

is

a figure (as they are figures), they have the potential of delivering it into the wrong hands.

But whose are the right hands? If “Life is over thereâ” when it becomes a metaphor, where is it if it does not? Is there any alternative to the privative fatality of figuration? These are questions that the lines back away from to then ask over and over with an urgency bordering on obsession. Before considering the litany of responses that make up the body of what is now one of Dickinson's most famous poems, we may better understand what is at stake for Dickinson in the apparent opposition between life as full presence and life as figure by placing these lines beside others from the same period (about 1862) that she wrote (or copied) on the same stationery bound in a very similar, slightly later fascicle (

figs. 21a

,

21b

, from fascicle

34

). The lines (now F 757) begin in a parallel worry over the figuration of address:

I think To Liveâmay be a

x

Bliss

To those

x

who dare to tryâ

Beyond my limit to conceiveâ

My lipâto testifyâ

I think the Heart I former

wore

Could widenâtill to me

The Other, like the little

Bank

Appearâunto the Seaâ

I think the Daysâcould every one

In Ordination standâ

And Majestyâbe easierâ

Than an inferior kindâ

No numb alarmâlest Difference

comeâ

No Goblinâon the Bloomâ

No

x

start in Apprehension's Ear,

No

x

Bankruptcyâno Doomâ

But Certainties of

x

Sunâ

x

Midsummerâin the Mindâ

A steadfast Southâupon the Soulâ

Her Polar

x

timeâbehindâ

The Visionâpondered long-

So

x

plausible

appears

becomes

That I esteem the fictionâ

x

realâ

The

x

Realâfictitious seemsâ

How bountiful the Dreamâ

What Plentyâit would beâ

Had all my Life

x

but been Mistake

Just

x

rectifiedâin Thee

x

Life

x

allowed click

x

Sepulchreâ

Wilderness

x

Noon

x

Meridian

x

Night

x

tangibleâ

positive

x

true

x

Truth

x

been one

x

bleak

x

qualifiedâ