Dickinson's Misery (29 page)

Read Dickinson's Misery Online

Authors: Virginia; Jackson

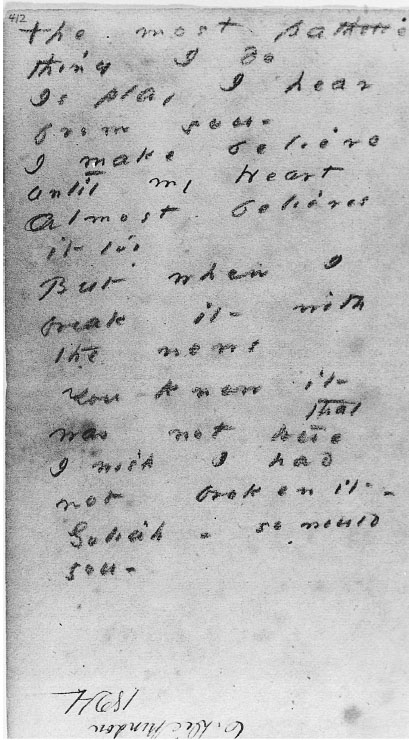

The most pathetic

thing I do

Is play I hear

from youâ

I make believe

until my Heart

Almost believes

it too

But when I

break it with

the news

You knew it

that

was not true

I wish I had

not broken itâ

Goliahâso would

youâ

55

I suppose that we could read these lines (or we can, now that the flyleaf has been excised from Irving and the lines have been printed) as Mill's “lament of a prisoner in a solitary cell,” or as an overheard song, or a soliloquy, or as Vendler's “performance of the mind in

solitary

speech.” And I suppose that if we considered them within those received phenomenologies of lyric reading, we might say that it does not matter who or where Dickinson's “Goliah” was, since the address to him or her was obviously so figurative (rather like, say, “Danny Boy” in a Scottish ballad Mill does not invoke), and it does not much matter when or where they were written. Yet if we happen to know that they were written in the early 1870s, and that Dickinson once compared Susan to “Goliah” in a letter in 1854 (L 154), and that in 1869 there was a celebrated discovery (which turned out to be a hoax) in Susan's native upstate New York of “the American Goliah,” then we might think that the lines on the flyleaf were the draft of a letter-poem to Susan. “The American Goliah” (a story all over the papers, including the Springfield

Republican

, in October 1869) was a ten-foot figure of a man “discovered” near Syracuse, about which there immediately ensued a debate “whether the colossal figure [was] a petrifaction or a piece of statuary.” A widely circulated ode entitled “To the Giant of Onondaga” consisted of a direct address to the figure, apostrophizing it to “Speak Out, O Giant! ⦠thy story tell,” in order to solve the controversy.

56

If the flyleaf lines were the draft of a letter to Susan, we could read “Goliah” as a name for exactly the figure of address I have been attempting to describe, or that Dickinson attempted to resist, the illusion created by apostrophe: the fictive figure with a no longer animate face. On this reading, Susan's lack of personal response in that moment meant that she could only be imagined as a petrified, and mute, figure of address. Yet if the first reading of the flyleaf lines is too indefinitely metaphorical (Emily Dickinson as folk song), the second is perhaps too definitely, or quirkily, historicalâthough that history does shift toward metaphor, as history tends to do. Between those extremes there is the flyleaf from Dickinson's father's copy of Irving, a piece of paper already part of a printed book that fits into neither account of Dickinson's figure of address. It is even more unreadable, less responsive than the petrified face of “Goliah”; it does not sound or look like us.

Figure 23. Flyleaf torn from Edward Dickinson's copy of Washington Irving's

Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon

. Courtesy of Amherst College Archives and Special Collections (ED ms. 412).

In 1914, Susan's daughter and Dickinson's niece, by then named Martha Dickinson Bianchi (because, rather like Margaret Fuller, she had gone to Italy and married an Italian Count, though she came back to Amherst without him), published a small volume of the verse that Dickinson had sent to her mother. In her Preface, Bianchi explained: “The poems here included were written on any chance slip of paper, sometimes the old plaid Quadrille, sometimes a gilt-edged sheet with a Paris mark, often a random scrap of commercial note from her Father's law office. Each of these is folded over, addressed merely âSue,' and sent by the first available hand.”

57

Susan had not given her cache of Dickinson manuscripts to Todd and Higginson. Bianchi writes in her preface that she seriously considered burning them, but decided to publish them for the benefit of “the lovers of my Aunt's peculiar genius” (vi). In doing so, she omitted the addresses to “Sue” and printed each of them alone on a separate white page, untitled, as if she had brought her aunt back with her from Europe as a new

Imagiste

. The last poem in her volume evokes in its placement the pathos of what Bianchi calls “the romantic friendship” between her aunt and her mother. One can see why she chose it, since the temporal confusion that we have noticed in the lines that begin “I think to Liveâ” and “I cannot live with Youâ” also informs Bianchi's last poem, but this time it is the time of reading itself that proves difficult if not impossible to locate:

I did not reach Thee

But my feet slip nearer every day

Three Rivers and a Hill to cross

One Desert and a Sea

I shall not count the journey one

When I am telling thee.

Like the other opening lines of those other forms of address, this stanza opens by closing a possibility to which it must then attempt a different approach. But how can one approach a destination that has already been canceled

as

destination? How can one get from here to there when (to paraphrase Gertrude Stein) there is no there there? The second line's assertion that “my feet slip nearer every day” is logically baffling in its apparently willful denial of the situation that the first line has already stated as fact. In slipping from past to present tense, the line is not progressing but backing upâor, in Robert Weisbuch's phrase for such moves in Dickinson's poems, the lines are “retreating forward.”

58

They do so in order to recount in the fictive present a time the sixth line explicitly identifies as the time of “telling,” an encounter that can take place “When” I reach what “I did not reach.” As in “I think To Liveâ,” the line between history and fiction is here a treacherous one to tread, and yet for four more stanzas it is literally the line that the “I” does tread, her poetic “feet” (in Dickinson's usage, almost always a pun on metric writing) traversing “Three Rivers and a Hill ⦠/ One Desert and a Sea.” The lines' geography is reminiscent of “the hills and the dales, and the rivers” that Dickinson imagines in the early letter to Susan as the “romance in the letter's ride to youâ.” In the letter, we recall, Dickinson compares that romance to “a poem such as can ne'er be written.” Such a poem, however, was written: it is Poem 1708 in the Franklin editionâalthough in more than one sense, the poem slipped near its destination.

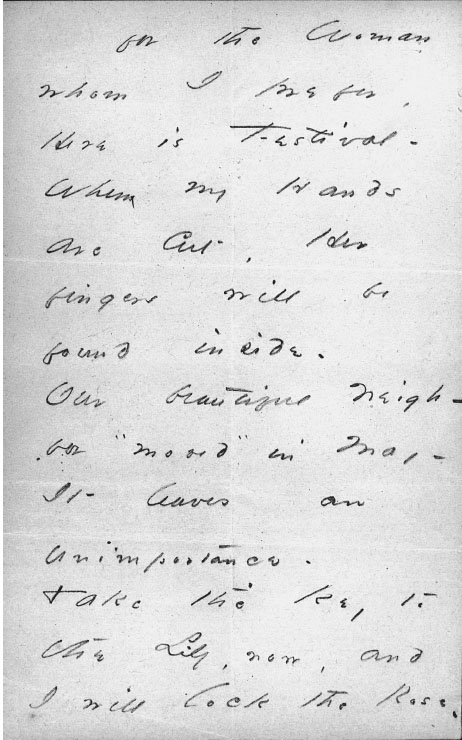

The text of these lines is available to us only by virtue of a transcript made by Susan herself. There is no manuscript version of this poem in Emily Dickinson's hand, no flyleaf, no slip of paper, no Quadrille, no Paris mark, no ad, no cut-out; the hand from which the published poem was taken is Susan's. If the hand-to-hand economy of written correspondence is to mediate our future reception of Dickinson's writing (as I have been arguing that both the historical form and figurative content of Dickinson's writing suggest that it should), then another message sent to Susan around 1864 acquires an uncanny sense for us (

fig. 24

): “for the Woman whom I prefer,” Dickinson wrote, “Here is FestivalâWhere my Hands are cut, Her fingers will be found insideâ” (L 288). Removed from the “Festival” of Dickinson's “Here,” from the time and place of her writing, not the

preferred reader of that writing but the readers deferred, future critics of Emily Dickinson would do well to notice that there are more than two pairs of hands complicit in this startling figure of address. Reading Emily Dickinson here and now, ours are the unseen hands most deeply “committed”: they are doing the cutting. Whether a literary text always reaches its destination or whether it has always already gone astray, whether Dickinson wrote letters or Dickinson wrote poems, it is worth returning to her forms of address with an eye to the way in which they have anticipated both alternatives and to the corrective they offer retroactively to Higginson's still influential version of Dickinson's writing as privileged self-addressâor as a private language addressed, lyrically, to all of us.

59

At least it is time that we cut more carefully, that we learned to tell the difference.

Figure 24. Emily Dickinson to Susan Gilbert Dickinson, around 1864. By permission of the Houghton Library, Harvard University.

“Faith in Anatomy”

A

CHILLES

' H

EAD

J

AY LEYDA

thought that it was a reminder to place a book order. David Porter thought that it was “a postage stamp with paper arms glued on.”

1

My students usually think that it is an avant-garde collage. The three-cent stamp with a picture of a steam engine on it stuck to clippings from

Harper's Weekly

that read “GEORGE SAND” and “Mauprat” (

figs. 25a

,

25b

) seems to have little to do with the lines Dickinson wrote around it. It would be difficult to print the lines in the patterns they assume to make way for the bits of print stuck between them. I will reprint them here

almost

as they appear in the Franklin edition (F 1174), taking the liberty of adding the variants in approximately the places they occupy on Dickinson's pages:

Alone and in a Circumstance

Reluctant to be told

A spider on my reticence

Assiduously  crawled

deliberately

determinately

impertinently

And so     much more at home than I

Immediately     grew

I felt              myself a

the

And hurriedly withdrewâ

hastily

Revisiting my late abode

with articles of claim

I found it quietly assumed

as a Gymnasium

for

where tax asleep and title off

peasants

Perpetual presumption took

complacence

lawful

As each were special Heirâ

only

A

If any strike me in the street

I can return the Blow,

If any take my property

seize

According to the Law

The Statute is my Learned friend

But what redress can be

For an offence not here nor there

not

anywhere

So not in Equityâ

That Larceny of time and mind

The marrow of the Day

By spider, or forbid it Lord

that I should specifyâ

Whatever these lines may be about, they are not (except in the most literal sense) about the stamp and clippings. Here, the objective enclosure or pasteon does not fill in the “omitted center” or restore the lines' “revoked ⦠referentiality” or explain their “strategies of limitation.”

2

Porter, one of the few critics to attend to these lines at all, has suggested that the reason that the “circumstance” of the text is withheld is that “it chronicles, in fact, the visit of a spider to a privy and particularly to an unmentionable part of the occupant's anatomy” (17). Jeanne Holland has taken up Porter's suggestion and expanded its reference to the larger domestic economy in which Dickinson made manuscripts like this one out of “household detritus,” incorporating her brother's and father's legal rhetoric into her “woman's work ⦠progressively refin[ing] her own domestic technologies of publication” against the masculine public sphere.

3

Both readers, understandably, want to domesticate the strangeness of the lines and their contingent circumstances, and it is worth noting that they do so by arguing that Dickinson blurs her culture's line between usefulness and waste, poetry and shit, a distinction made and unmade with reference to gender and the body. Both readers also identify the objects on the text with or as the subject in the text (“paper arms,” “her own domestic technologies”). But what

is

(or

was

) the relation between these lines, anatomy, gender, privacy, publicity, intellectual and material property, technology, circulation, social economy, and the blue-and-white stamp gluing together an author's name and the title of a novel? Is that relation legible or illegible in Dickinson's manuscript?